Society

Radical treatment for healthcare

By Hu Yinan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-16 08:16

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

A pharmacy worker dispenses medicine to a man at the Xincheng Community Health Center on Aug 31. As the patient lives in a pilot zone for the rural medical reforms, he received a 10 percent discount on the price of the drugs. |

Fall in patients

Health chiefs in all 32 pilot sites signed responsibility agreements in late June that bind them to "achieving comprehensive reform tasks" by March 31, 2011.

Bi Pumin, director of the city health bureau in Huangshan, said the most important indicator of success is whether or not people in towns and villages get cheaper access to healthcare.

However, this cannot be done quickly, he warned.

"Medical reforms in the 1990s and early 2000s attracted a great deal of money from (patients) and boosted health departments, but officials realized that if we left healthcare solely to the market, the people would suffer," said Bi. "That's why we must rebuild a public-purpose system led by the government. The problem becomes how we can introduce a competition mechanism to motivate workers."

The reform has reduced revenue considerably for a third of Huangshan's township clinics. Overall, the number of outpatients fell more than 60 percent during the first half of this year compared to the same period in 2009, which in turn has led to sharp decreases in the incomes of grassroots physicians.

Although township clinics have been stopped from profiting from drug sales, government subsidies have not yet caught up in many areas, posing a dilemma for managers.

Xincheng Community Health Center, Huangshan's highest-rated rural clinic in terms of performance, made 800,000 yuan in 2009 but has witnessed a dramatic decline in revenue following the reform.

Striking a balance between covering costs and providing public services is a challenge, said its director, Cheng Libin.

"With minimal subsidies, we're still pretty much on our own with operating costs," said the 37-year-old. "We can probably earn 400,000 yuan this year, provided each of our 30 or so staffers brings in about 15,000 yuan in revenue.

"Any more would be a stretch, unless we're determined to make profits again. There's still room for profit," he added, referring to the unnecessary infusions ordered by doctors looking to make extra money.

On average, about six out of 10 inpatients at rural clinics are given infusions, according to Ye Lianggui, Xincheng's deputy health director. His bureau has ordered all clinics to cut inpatient infusion rates by 70 percent this year.

Even Cheng's center still gives infusions to half of its patients, however.

"It's a conflict," said the health center boss. "If they want us to meet the revenue requirements, this is how we're going to do it. We would've been much better off had these missions not been assigned but that would be a great financial burden on the government."

In response, Ye acknowledged infusion rates are difficult to contain under the circumstances but insisted the reform is on the right track.

"If we just let it go and allow them to make profit, the tasks of grassroots health workers would've been extremely simple: Just go catch patients and butcher them," he added. "Without this reform, medical costs would only go up year after year."

Doctors' fears

In rural areas, problems generated by previous market-driven reforms are causing fresh headaches as officials try to restructure village clinics into public health facilities.

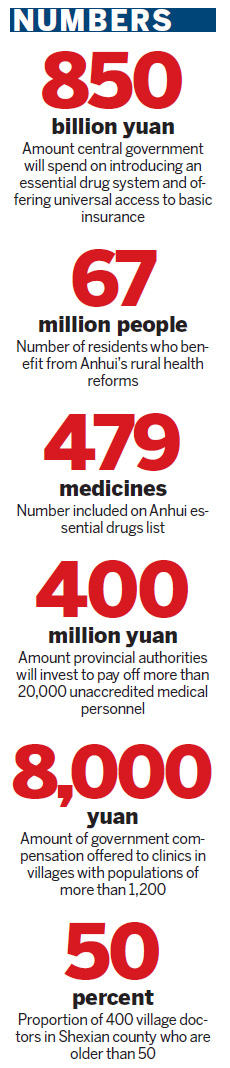

Under the new initiative, provincial health authorities pay annual compensation of 8,000 yuan to each clinic in a village with a population of more than 1,200.

However, 17 of the 32 pilot sites said in their assessment that the earnings of rural doctors had gone down exponentially and needed immediate intervention.

Dongzhi, one of the pilot counties, reported that its doctors on average made 20,000 yuan a year before the reform - 70 to 80 percent coming from drug profits. The regulation of drug prices will cut estimated incomes this year to just 35 percent of that, according to the submitted assessment.

Zhang Gongyong has been the only doctor in the mountainous Qianshan village since 1974 but is not qualified to receive the 8,000 yuan compensation as he serves only 400 people.

The 56-year-old made 8,000 yuan at his clinic in 2009, as well as 2,000 yuan from growing tea and oranges and 1,200 yuan from government subsidies. However, the latest drug pricing regulations mean his total net income will fall by 5,000 yuan this year.

For the time being, Zhang is fine with the changes. "If other people can survive, so can I. Somebody's going to have to work for public health in villages," he said.

|

||||

"Fewer kids are studying medicine," said the veteran medic. "People can make at least 30 to 40 yuan a day as migrant workers. That's not the pay you can expect as a village doctor."

He added: "I'll be here until I'm too old for it. There's no retirement."