Society

Bountiful land faces barren future

By Li Jing (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-28 08:31

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

Cui Xuefu grazes his cattle in a cornfield near an erosion gully about 50 meters long in Binxian county, Heilongjiang province. Northeast China has long been famous for its rich black soil. [Photos by Feng Yongbin / China Daily] |

Reversing the trend

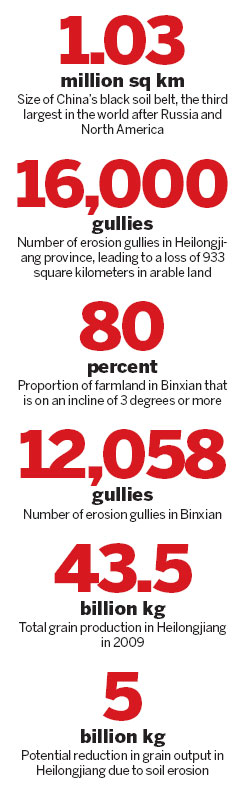

Total grain production in Heilongjiang hit 43.5 billion kg last year, contributing to a national output of 530.8 billion kg, according to figures from the National Development and Reform Commission, the country's economic planning body.

However, studies by the Soil and Water Conservation Research Institute show the loss of farmland due to soil erosion could cost Heilongjiang 5 billion kg in grain output.

To prevent the potential threat to China's food security, authorities are throwing millions of yuan to relieve the soil and water erosion in the black soil region.

Zhang, who has been in the field for more than 20 years and works with farming communities on conservation projects on a daily basis, knows every gully in Binxian county. He said that building check dams in cracks has proved an effective way to prevent them from expanding further.

"The soil flushed down (by the rainwater) accumulates on the dams, which gradually fills the cracks," he explained. "This method is especially useful for small gullies."

Check dams have been built in more than 4,600 gullies across Binxian county, with work still ongoing. Each project is expected to cost about 10,000 yuan ($1,490).

"The central government provides an annual fund of 4.8 million yuan for water and soil erosion conservation, along with a 1.92-million-yuan investment from the provincial authorities and 480,000 yuan from the county," said Zhang.

Unfortunately, there is no quick fix for soil erosion. For slopes less than 5 degrees, research suggests changing direction of the ridges carved by farmers so that furrows can hold rainwater. Constructing terraces or small blocks in the ridges on inclines of between 6 and 15 degrees can also help prevent black soil loss.

When experts attempt to persuade farmers to employ these tactics, however, they often meet with strong resistance.

"Farmers are reluctant to change," said Yin Jiafeng, a researcher with Heilongjiang's Soil and Water Conservation Research Institute. "Building small blocks or terraces means taking up farmland, which of course will reduce farmers' income. So it's hard to encourage such practices."

The county government has also urged villagers to stop farming on hillsides steeper than 15 degrees and instead plant trees.

"Reducing agricultural activities can prevent soil erosion, while trees can better conserve the land," added Zhang.

Farmer Hu Jinghe said he stopped cultivating crops on about one-third of his 60 mu of farmland in Pingyi village several years ago.

According to the central government's policy on returning land from farming to forestry, Hu can get an annual subsidy of 160 yuan per mu for eight years. After that, the subsidy drops to 90 yuan per mu for another eight years.

As the policy cannot cover all the households in Binxian county, though, Zhang said it has become more difficult to persuade villagers to stop farming.

"All I can give them is free saplings, not compensation," he added.

|

|

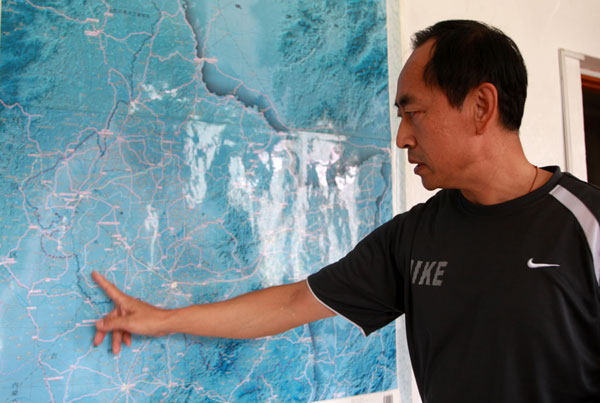

Yin Jiafeng, a researcher with Heilongjiang's Soil and Water Conservation Research Institute, shows the areas worst affected by soil erosion on a map. [Photos by Feng Yongbin / China Daily] |