Profiles

Artisan has a real feel for felt

By Bao Daozu (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-03-25 07:18

|

Large Medium Small |

|

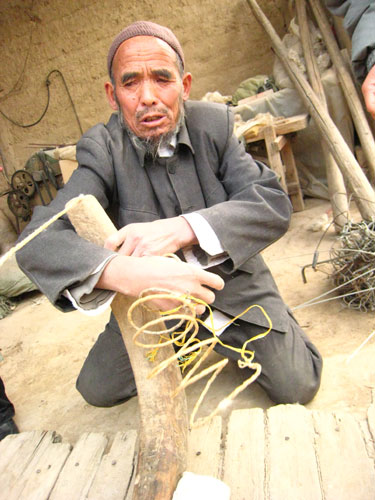

Master felt-maker Yang Deming, 68, fluffs wool in the courtyard of his modest home in Dongxiang, Guizhou province in this file photo. [Fan Zhen/China Daily] |

DONGXIANG, Gansu - Yang Deming's eyes beam and his face lights up when he gets the chance to talk about making felt handicrafts with his hands.

Yet, when talking about the future of his craft, he experiences a feeling of helplessness and despair, realizing very few young people would like to take up the tradition, which they see as monotonous, dirty, manual work.

Felt-making has been a lifelong profession for this 68-year-old man, who picked up this ingenious method of turning fleece into warm clothing at the age of 16.

"Twenty years ago, nearly every family had felt mattresses on their beds," recalled Yang, who also custom makes felt hats and gloves.

The cold weather and chilly wind in the mountains made felt mattresses, boots and hats a daily necessity for local Dongxiang people.

The ethnic group has lived for eight centuries in the dry, forbidding mountains that have rendered this county in Northwest China's Gansu province one of the most isolated and poorest places in China.

Scholars believe that the Dongxiang people descended from the Mongol soldiers in Genghis Khan's army who eventually settled in Gansu during the 13th century when the Mongols ruled China in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368).

Felt-making, a common craft in ancient Central Asia, was included in the national list of intangible cultural heritage in 2008.

Surrounded by boundless mountain ridges and yellow terraced fields, Yang's bare shabby yard for making felt is just by the edge of a mountain ravine. Wind blows dust from the terraced fields right into it.

"I haven't made any felt this year because my son fell ill and the three workers demanded a raise," Yang sighed.

Like elsewhere in China, modern ways have been making inroads into the lives of the young generation, even in this remote area.

"It used to be a family business, but nowadays most of the young prefer to make fast money in cities. They think felt-making is time-consuming and exhausting," Yang said.

"But it used to flourish," continued the experienced artisan while felting a three-meter wooden bow which he used for decades to fluff wool.

"It was very popular in my father's generation. Most of the elderly villagers know more or less how to make felt."

Making felt is anything but an easy job: sorting sheared sheep fleece by dividing it into different grades; teasing the wool with a bow; pouring boiling soapy water over the fleece on reed mats; rolling the mats and kicking them back and forth for hours; folding the brims and patching the weak areas with more wool.

"It takes three men three hours to make a two-meter-long felt mattress," Yang said.

The felt-maker admitted that the process required physical strength and manual dexterity, while it was good for health.

"You have to eat to store strength before work, but never too much. If we have to make five felt mats that day, we eat five meals. Eating less and more frequently keeps me as fit as a fiddle," laughed the gray-bearded man, stretching his arms and legs.

In the 1980s, carrying the 30-kilogram felt-making equipment and food for several days, Yang and two partners trudged along the Hexi Corridor (part of the neighboring Ningxia Hui autonomous region along the Yellow River) to make felt carpets, hats and clothes for locals to earn extra money in the slack season.

He chose the route because most of those locals were also Muslims with whom he shared the same beliefs and living habits.

"When we came to a village, we collected sheared fleece and offered to make one or two felts for a family for free and they would provide us with shelter and food," Yang recalled.

The first two handmade products would stand as samples and advertisements that drew more clients.

"At most we could make five felt mattresses a day and earn 5 yuan (75 cents) each," Yang said. "But there was a time when business was gloomy and we had to sleep in the straw."

Half a century of felt-making experience makes Yang one of the most respected craftsmen among the Dongxiang people, as most of his peers in the trade have sought other ways to earn a living.

"I can tell first-class wool from the rest at first sight," the hale and hearty artisan said proudly.

Over the past decades, the price of a felt mattress has risen to 250 yuan, including 80 yuan or so for wool, leaving a net profit of about 50 yuan for each workman.

With the advent of other alternatives for keeping warm, the demand for felt has dwindled year by year. Only 350 mattresses were made in 2009, and the number of felt makers in the county has shrunk to two.

"I never blame my three sons for not wanting to continue the business, because they have their pursuits and the profits of felt-making are far from enough to cover their daily expenses," Yang said.

"But felt-making should not be a lost art. After all, it is more of an intangible asset of the Dongxiang's long history and culture than a simple profit-oriented craft."

Fan Zhen contributed to this story.

| 分享按钮 |