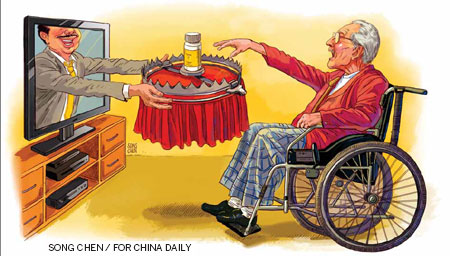

Not what the doctor ordered

Anger is growing over misleading adverts for medicines, as He Na reports in Beijing.

Li Jing used to get on well with her parents. Whenever friends or colleagues asked for her secret, she always replied that obeying her parents' wishes and helping to keep them cheerful were her best tactics.

However, family harmony was wrecked two years ago after one of her father's friends introduced her parents to a late night health program on the radio.

|

"It's called a 'health-advice' program, but actually it just contains adverts for various medicines, which are touted as being able to eradicate all disease. Because both of my parents have a number of chronic conditions, they quickly became regular, dedicated listeners," said Li, 33, who works as an accountant at a hotel in Dalian, Liaoning province.

"Most of my parents' pension went on fake medicines the program strongly recommended. They have been cheated several times already, but still haven't learned the lesson that the media is full of these illegal ads for fake medicines," Li said.

In April, when Li's father came down with tracheitis, an infection of the windpipe, the doctor recommended that he should receive hospital treatment for a couple of days. However, Li's father insisted on buying medicine he'd heard advertised on the radio instead.

He argued that a large number of patients with similar symptoms had called in and praised the medicine, claiming that their symptoms were completely gone and had not recurred after using the treatment over an extended period.

"I objected, of course, but my father was adamant that he would buy the medicine. It was the first time that we'd quarreled in public. He yelled and pointed his finger in my face and said he knew that I regard him as a burden," recalled Li.

Realizing her father wasn't going to change his mind, Li had no option but to watch him spend 3,500 yuan ($507) on three courses of the treatment.

"Just as I'd feared, he didn't get better, but rather grew worse after taking the medicine. We had to rush him to the hospital one day when we discovered he was having difficulty breathing," she said.

"The doctor diagnosed him as severely asthmatic and said we were lucky to have sent him in good time. If we hadn't done that, the consequences could have been much, much worse," said Li.

In the end, her father spent two weeks in hospital at a cost of a further 20,000 yuan.

Li's parents are not the only ones taken in by illegal adverts for medicines. Reports of similar scams nationwide make up a long, depressing list, especially as medicines of this sort are hugely popular among the elderly and those from low-income groups.

Data from the China Food and Drug Administration show that more than 179,000 illegal medical adverts were investigated in 2012, almost three times the number in 2010.

Zhuang Yiqiang, deputy general-secretary of the Chinese Hospital Association, conducted a survey last year into newspaper adverts for medicines and found that around 40 percent of them were illegal. Experts have warned that these adverts, which have flooded the media, have drawn a massive number of complaints from the public.

"Medicine should cure ailments, but these misleading adverts waste people's money and pose a threat to their health and livelihoods. They can also make people distrustful of the authorities that have failed to crack down on them, a course of action I think is essential," said Lu Jiahai, professor at the School of Public Health at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou.

A joint campaign

In a bid to reassure the public, the government has ordered a three-month campaign aimed at tightening supervision over advertisements for medical equipment, pharmaceuticals and health foods in the media and on websites from early May until late July.

The campaign was launched on April 22 by eight government agencies, including the State Administration for Industry and Commerce, the State Council's Information Office and the State Administration for Traditional Medicines.

The campaign will target adverts that make false claims, exaggerate the efficacy of the product or deliberately confuse supplements with real medicines. Also in the spotlight are those who infringe image and name rights of experts, celebrities, research institutes and patients for promotion, or have failed to gain government approval.

"We will work with related departments to integrate the supervision of resources and - in the form of joint warnings, announcements and inspections - comprehensively use financial punishments, administrative penalties and criminal sanctions to punish violators," said Gan Lin, vice-minister of the SAIC.