No longer at home in their hometowns

Left-behind children make do without their parents

Gao Lili rarely goes home anymore. In fact, she rarely even refers to it as "home".

For the past three years, the 17-year-old has been the only person living in the shabby, two-story village house her parents own in Henan province.

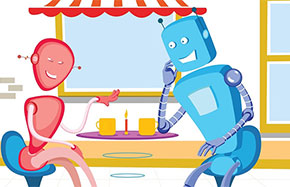

|

|

A pupil at Wenxing School in Gushi county, Henan province, eats dinner. The school only accepts the children of migrant workers. PHOTOS BY XIANG MINGCHAO / CHINA DAILY |

"It's so deserted here," said Gao, explaining that only two other households — a couple in their 80s and a 73-year-old bachelor — still remain. Everyone else has gone, some temporarily for work, some for good.

This scene is fairly typical for a village in Gushi, a poor agricultural county. Its once-abundant labor force left for large cities when the wave of urbanization started in the 1990s. Roughly a third of its 1.7 million residents are now migrant workers.

As a result, the county is home to 186,000 "left-behind children" under the age of 18, with either one or, in most cases, both parents working away from home. They account for half of all students in grades one to nine, according to research by the county branch of the All-China Women's Federation.

Gao was born in Qingdao, a developed coastal city in Shandong province, where her parents worked. She was sent home to the family's native Gushi to start school 10 years ago, along with her sister, who was 14 at the time.

Without hukou, or permanent residency, in the city in which they live, migrant workers must send their children home to take advantage of China's free nine-year compulsory education. Otherwise they need to pay high fees to a nearby private school.

Gao's parents both worked on construction sites and originally asked a neighbor in the village to take care of the two girls. Soon after, however, her mother was diagnosed with uremia and returned from Qingdao. She died in the summer of 2009, with the family steeped in massive debts from hospital treatment.

To help pay the bills, Gao's older sister dropped out of school and went in search of employment.

"All of a sudden, I was completely alone," Gao recalled. "It was hard for me to adapt. I was overwhelmed by sadness after losing my mother, and I couldn't sleep at night because I felt scared."

She said she prefers to stay in her school's dormitory than travel the two hours it takes to get to her village, even on weekends and holidays.