Center gives parents a lesson in encouragement

For 13 years Feng Derong practiced the only style of parenting she had known — education through fear, and occasional violence.

"I'd often lose my temper and scold my daughter when she made a mistake. I would even beat her if she made that mistake again," the Beijing grocery store worker said.

|

|

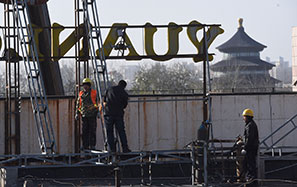

A migrant father feeds his son while waiting for the train at Hefei railway station in Anhui province. Roughly 15,000 migrant parents have taken part in the Maple Women's Psychological Counseling Center's free program to learn the best way to teach their children.Photo provided to China Daily |

It was the way her mother had taught her as a girl growing up in East China's Anhui province, she explained.

Things have changed, however, since Feng and her 13-year-old daughter, Wei Wanying, took part in a free program for migrant worker families, run by Maple Women's Psychological Counseling Center.

During the program, which involves parents and children attending a two-hour workshop every Friday for six weeks, professional psychologists teach how to improve communication and build mutual respect through lectures and games.

"It helped me see that a child's mood can be greatly affected by the actions of a parent," said Feng, who moved with her family to the capital two years ago. "Scolding and beating them is not the way to teach a child.

"I never used to praise my daughter before, but now I see she's happier when I encourage her," she said. As a result the sixth-grader at Haidian Xingzhi Experimental School is performing much better in class. "She scores 80 in math tests (well above a pass). Before, she usually failed."

Wei agreed, and said she has witnessed a real change in her mother. "She gives me confidence now, and she doesn't criticize me in front of others," she said. "I feel I have dignity."

Same goal

Roughly 15,000 parents have taken part in the program since it started in 2007. Wu Fei, a project officer at the center, said each class has about 50 people.

The center also cooperates with 15 schools for children of migrant workers in Beijing, setting up after-class counseling sessions and other activities, all with the same goal: improving relationships.

For example, the weekly workshops feature trust exercises, including one in which a parent is blindfolded and must rely on their child to guide them through an obstacle course. In another, parents are asked to list their child's qualities.

Li Guangqin, who has an 11-year-old daughter, said after attending the class she had tried to avoid getting into arguments with her husband to create a better family atmosphere.

"Children can be affected by quarrelling parents, so we're trying hard not to fight any more," said the hotel worker from Henan province. "We're also trying to show our girl more affection on a regular basis."

Like in Feng's case, the change has not gone unnoticed. "My mother seems more concerned about me than before," said Qin Nan, Li's daughter. "After I finish my homework, she checks it and answers the questions I don't know."

The impact of the Maple program is obvious, according to Wu, who said many parents quickly realize the importance of family education and change their attitude, showing more respect and love toward their children.

First teacher

According to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' Social Construction Blue Book, people without permanent residency, or hukou, made up 40 percent of Beijing's population of 20 million in 2011.

The report predicted that figure will grow rapidly, too, which means the Maple center is likely to have no shortage of customers in the near future.

"According to our research, migrant workers generally lack family education," project worker Wu said. "They often pass responsibility for educating their child onto schools. They just don't realize they are a child's first teacher, or that families play a great role in the psychological health and growth of children."

The problem, she said, can largely be put down to the low education level of most migrant workers, as well as the time they spend at work compared with time spent with family.

Liu Xuejun, vice-principal at Haidian Xingzhi Experimental School, one of the center's partners, can attest to the pressure put on teachers to take on an almost parental role.

The school, opened in September 1994, has about 850 students, most of who, she said, come from migrant worker families in which the parents "pay more attention to making money than caring about their child's education".

She confirmed that many of these parents had received little education themselves, and believe raising their child is entirely the school's responsibility.

"But our teachers are often busy preparing lessons and checking students' homework," Liu said. "They don't have time to communicate with parents about each child's performance in class."

That is why a program such as the one run by the Maple center, which offers in-depth counseling and guidance for parents, is so vital.

"The parenting workshops have received a really positive response," she said. "This is only the second year our school has participated in the program, but I can see that many parents have changed a lot.

"It's a great platform to boost understanding and communication," Liu added. "I only hope more parents take part."