Boredom, safety are problems for rural kids in cities

Organizations attempt to fill the spare time with daily activities, sports for young visitors

Zhang Xinlin's excitement about spending the summer with his parents in Beijing quickly disappeared when he realized he and his elder sister could not go anywhere, and had to settle for playing cards inside the family's rented apartment every day.

The siblings arrived in Dongshagezhuang, a large community dominated by migrant workers on the outskirts of Beijing, in early July.

|

|

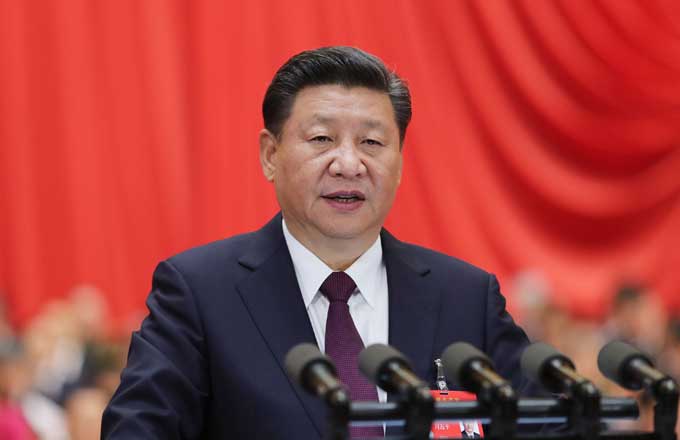

Migrant children play paper-folding games at the Mulan Activity Center in the Changping district of Beijing on Aug 7. The center has a library and organizes games.xu huiyan / for China Daily |

"We're not allowed to go out to play because our parents worry about there being bad people on the streets," the 7-year-old said.

Zhang is from a village in Huanggang, Hubei province, and for most of his life has been in the care of his grandfather.

"It's so boring here," said Ni Junhao, 10, who was visiting his electrician father in the community, his third consecutive summer in Beijing. He complained that, despite being in the capital for more than 40 days, he had spent only one with his father, when they went to ride bumper cars in Chaoyang Park. He will return home to his village in Nantong, Jiangsu province, in mid-August.

Nearby, Hu Tian and her sister said their only pastimes are homework and watching their mother play mahjong.

Stories of boredom are common among rural children spending their summer vacations with parents in cities nationwide. One organization that attempts to relieve the boredom for migrant children in Dongshagezhuang is the Mulan Activity Center.

"Most migrant workers rent rooms of 10 to 20 square meters, where they eat and sleep, but children are vivacious and energetic, so it's really painful for them to live in such cramped conditions," founder Qi Lixia said.

Located in a traditional courtyard home, and with room for a maximum of 40 children, Mulan Activity Center is open from 8 am to 8 pm six days a week. Children can read books, play chess and darts, enjoy sports facilities and surf the Internet.

Most facilities are secondhand, donated by charitable foundations or individuals.

"Children can also play badminton in the alley outside," Qi said. "They love playing ping-pong, but we can't afford a table.

"Money has always been our biggest issue as we are not sure whether foundations will continue supporting us next year, and so far we have never received funds from the government for this project," she said.

Sometimes volunteers from universities teach the children handicrafts, environmental protection and personal safety skills in case of fires and earthquakes.

Although demand is huge, Qi estimated that less than 10 NGOs in Beijing provide services like those offered by her organization.

There are no reliable statistics to show how many rural children go to cities during the summer school holiday, which lasts about two months.

A report by the All-China Women's Federation in May said there are almost 100 million minors whose parents are migrant workers. Of these, 61 million are "left-behind children", which means they are growing up in villages without their parents.

Safety concerns

"During summer, most migrant workers' children are left at home unsupervised, so safety is a big issue," said Sun Heng, director of the Migrant Workers' Home in Beijing, an NGO dedicated to improving the rights of the migrant population.

"There are a lot of demolition and construction sites in these communities. Imagine their children running around; the chances of them getting hurt are worryingly high."

He said the media often reports on children being drowned or hit by cars, and said they are also vulnerable to child traffickers and sexual predators.

On Aug 8, a 13-year-old girl was left alone in her parents' dorm in Taiyuan, the capital of Shanxi province, and was sexually assaulted by a migrant worker who lived in the community, according to the Shanxi Evening News.

China National Radio also reported on

July 15 that a court in Ningbo, Zhejiang province, had found migrant workers' children account for 70 percent of all juvenile victims in sexual harassment cases.

Children are not only victims of crime, but also sometimes become involved in criminal activities themselves, partly due to the lack of parental guidance.

Yang Chang, a judge in Beijing's Mentougou district, said summer is a peak time for crimes committed by minors, especially migrant workers' children, with intentional injury and public disorder the most common offenses. Most defendants are aged 12 to 14.

"Young offenders and victims have more time to go out independently, and their parents can't watch them at all times," she said, adding that her team gives lectures in schools on child safety.

Sun said the establishment of child activity centers in every community in major cities would help prevent crimes and accidents.

"What these children lack most is safe places for them to go to play when their parents have to work," said Qi from the Mulan Activity Center.

Crowded communities

Since 2009, Dongshagezhuang, near the Sixth Ring Road in Beijing's Changping district, has grown into a community populated largely by migrant workers.

According to Qi, about 1,000 native villagers and an estimated 50,000 migrant population live there.

Most male migrant workers do jobs related to construction and domestic renovation, or else work in sales or drive unlicensed taxis. Most female workers, meanwhile, make a living as restaurant waitresses or housekeepers.

"There are no statistics on the migrant population, but I estimate there are more than 2,000 migrant workers' children, and the number is bigger during summer, as many left-behind children come to visit," Qi said.

The community has a library, but it is always closed. China Daily found a phone number for the library online, but the employee who answered said she knew nothing about the library and then hung up.

Cheng Huoqing at the Cultural Service Center in Beiqijia township, which oversees cultural affairs in Dongshagezhuang, said community activity centers are often used as meeting rooms for village committees or rehearsal rooms for the senior citizens' dance society.

He explained that the difficulty with constructing cultural and sports facilities comes from the fact that feasibility studies are based on the number of permanent residents, not the migrant population.

"In suburban areas such as Dongshagezhuang, the influx of migrants has put great pressure on public facilities and resources," Cheng said. "During hot summer days, water and electricity supplies are serious problems, so facilities for children seem less urgent for the government."

Life lessons

Zhang Yan, a professor at Beijing Normal University, argues that instead of pumping more money into facilities or expecting immediate action from the government, the emphasis should be on improving parents' awareness of child safety issues.

"You shouldn't think all migrant workers' children should live the same life as urban children. Most are happy with the status quo," she said.

The professor has been studying the education of migrant workers' children for about 10 years.

"Livelihood is always the priority for migrant workers, and there is nothing wrong in the children seeing their parents' real life and the hardship of making money," she said.

Cao Yin and Yan Ran contributed to this story.

|

|

|

| Yang Yaohua, 11, watches TV at a rented house near the construction site where his parents work in Wuhan, Hubei province. Liu Kun / China Daily | Chen Haotong, 10, waits for a bus after finishing his summer courses in Zhengzhou, Henan province. Xiang Mingchao / China Daily | Han Lei, 12, helps his father sell watermelon in Zhengzhou, Henan province, during his summer vacation. Wang Zhenzhen / for China Daily |

| Wuhan | Zhengzhou | Zhengzhou |

| Employer-sponsored camp offers adventure, education | Youngster finds country life preferable to urban areas | Selling watermelons: a boy's first taste of city life |

|

By china daily Yang Yaohua, 11, came to Wuhan from Kaixian county, Chongqing, for the summer vacation. A villager escorted Yang and his elder sister, as well as two cousins, to the city, where their parents work at a construction site. They crammed into a rented apartment, which their parents shared with other workers, and slept on a makeshift bed made from a mattress and sheets resting on recycled bottles filled with water to give a cooling effect. They kept each other company, watched TV and played games after their parents went to work at 5 am. They wrote their homework outside on an abandoned canteen table, where it was cooler than in the room without air conditioning. When they accompanied their parents to the construction site, they played table tennis and billiards in an entertainment room set up for the workers. Yang said he did not really miss his parents while living with his grandparents in Chongqing. The most exciting adventure for Yang during the vacation was a four-day summer camp for left-behind children sponsored by their parents’ employer, China Construction Third Engineering Bureau. The camp started on Aug 12 with an English class given by Adams Musa, a Nigerian doctoral student at Huazhong Normal University who has taught as a volunteer for three years at Chunmiao Primary School in Wuhan. The class was the first English lesson for most of the 12 children at the camp, who were all from rural areas. They also enjoyed a variety of activities in the four-day event, including outdoor and first-aid training, mental health education and a day trip to Wuhan. Liu Kun contributed to this story. |

By He Dan Chen Haotong, 10, found his summer vacation in Zhengzhou, capital of Henan province, boring, even though he can be with his parents, who sell wonton near a university campus. “In our village, I can catch shrimp in rivers and play beanbag games with friends, but here, I haven’t made any friends,” said Chen, who had joined his parents in Zhengzhou for nearly a month with his elder sister. Chen went to a zoo with his sister this summer but he said he realized animals in a zoo lack freedom, just as he does in the city. Chen’s father, Chen Yanmin, said he plans to take the two children to see the Yellow River, which he said he believes his children will be excited to visit. During school days, the two live with their grandparents in a village in Xinyang, Henan province, and they can see their parents only during the summer or winter vacations. Chen Haotong’s parents said they were considering finding a school for him in Zhengzhou so that he can stay with them and have a better education. They have signed him up for summer courses, so the boy had to take a one-hour bus ride on his own to attend English and math classes every afternoon. Chen Yanmin was a little worried about his son’s safety on the road, but neither he nor his wife has the time to take their son. In his spare time, Chen Haotong helps his parents at their wonton stand. Urban life is full of new experiences for the boy. He was curious to see most clients staring at their smartphone screens, busy surfing the Internet. “He need to adapt himself to the city,” the father said. Qi Xin, Li Feilong and Zhang Yongfei contributed to this story. |

By He Dan On July 31, Han Lei got up around 5 am to harvest watermelons with his father and load them on a truck. After a four-hour ride, the 12-year-old arrived in Zhengzhou, capital of Henan province, to start his first summer vacation in a big city as a street vendor. Han and his father traveled about 160 kilometers to Zhengzhou as the watermelons his grandfather grows fetch much higher prices there than in their hometown in Kaifeng, known for its high yield of the fruit. “Cities are beautiful but the only problem is that there are too many cars moving fast,” Han said. “I want to live in an urban area when I grow up.” Han’s father told his son how to read traffic signals and urged him to be extremely careful when crossing roads. Han, who will start sixth grade in a rural primary school after the vacation, is a good helper for his father as he can independently weigh the melon a customer selects, count money and give change. Han’s father, Han Bin, a divorced migrant worker, has worked on construction sites for more than six years to feed his three children. However, he gave up manual work temporarily after seeing several workmates get sunstroke each day in this scorching summer. The 43-year-old said his family lives in a makeshift shelter in an underground passage but it was a bad choice as it attracts many mosquitoes after torrential rain at night. Their watermelon sales while in the city were not good either as they had to move their truck from time to time to avoid surprise inspections from chengguan, or urban patrol officers. Qi Xin and Wang Zhenzhen contributed to this story. |