Family networks

Social media are changing China's parent-child dynamics both online and offline, enticing some children to resort to cloak-and-dagger measures to protect their privacy. Xu Lin reports.

Lin Zhishan's greatest joy is browsing her son's micro blog - without his knowledge. Her 24-year-old son, who's studying in Japan, has no inkling his mother monitors his online social networks. And Lin hopes to keep it that way. "He only tells me the good news and never lets me know about anything negative," the 51-year-old mom from Liaoning province's capital Shenyang says.

"If he knew I secretly follow him online, he'd never post about the hardships of living overseas. I just want him to have an outlet to blow off steam."

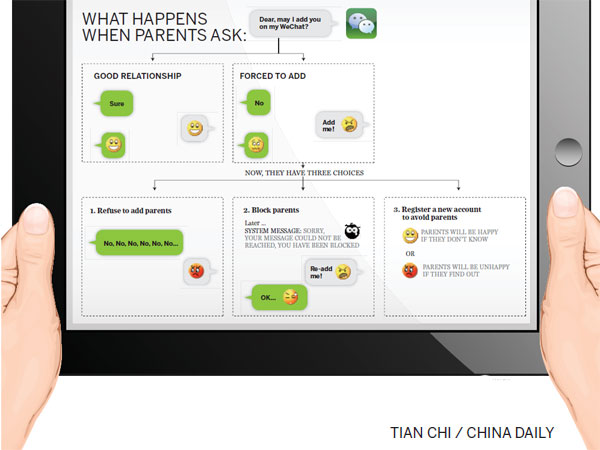

Lin is one of a growing number of Chinese parents who interact with - or spy on - their children's social networking sites, such as micro blogs and WeChat.

But many people don't want their parents to follow their every post.

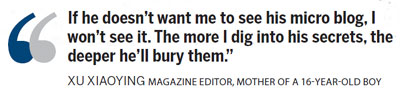

Magazine editor Xu Xiaoying says her 16-year-old Yuan Jinshun blocked her from his micro blog after a week - even though it was his suggestion she start an account.

"I learn about his interests through his micro blog," says the 42-year-old from Hunan's provincial capital Changsha.

"I followed his idols, such as Taiwan singer Rainie Yang, on Sina Weibo. I even took him to Yang's concert."

The high school student says having an SNS relationship with his mother proved too invasive.

"I post what's in my heart on my micro blog because I need friends' comfort," Yuan says.

"But I couldn't post freely with mom reading. It's better to communicate with her in real life. I'll tell her what I want her to know."

However, he says such SNS relationships with his mother bring them closer. For instance, he's happy his mom likes the songs he re-posts.

Xu takes a different tact from Lin, who employs a cloak-and-dagger approach to track her child on SNS.

"It's OK he blocked me," Xu says.

"If he doesn't want me to see his micro blog, I won't see it. The more I dig into his secrets, the deeper he'll bury them."

In other cases, parents encourage their children to hide their personal affairs from the public view.

Liang Yun says her mother would scold her for sharing too much about her personal life on SNS. The 26-year-old public relations worker, who lives with her parents in Beijing, says she felt relieved after she blocked her mother from her WeChat.

"We have different views and values," Liang says.

"Mom commented I was posting flippantly and she would post that it's improper to share everything online. Her words embarrassed me."

Liang uses her WeChat Friends Circle to share her inner feelings, including those about her family. Her mother regularly prowled her circle, until the daughter finally pushed her out - unbeknownst to her mother.

Then, Liang's mother used her husband's mobile phone and asked her daughter why her husband could read Liang's recent posts but she hadn't seen any for a long time.

Liang told her mom it was because of her phone's unstable Internet. She took the phone and pretended to fix the problem, while swiftly and secretly unblocking her mother on her own phone.

"I can't grumble about my mom on WeChat anymore," Liang says.

"Now I just don't post things she doesn't want to see or things I don't want her to see."

Some people are getting around the nosy parent problem by creating two SNS accounts - one for family and one for friends.

That's the approach 21-year-old Yang Yunmeng takes. And the university student in Guangdong's provincial capital Guangzhou says she doesn't feel the least bit guilty about it.

"I try to balance protecting my privacy and my parents' feelings," Yang says.

"My family doesn't know about my other account. But I think they'd understand. We all need more space and freedom."

Her mother, who only gives her surname, Yang, tells China Daily she'd understand if her daughter uses two accounts or blocks her on SNS.

"Everybody has their secrets," the mother says.

"Parents also have things they keep from their kids."

Unwittingly echoing her daughter, she says: "We all need space."

But while Yang Yunmeng keeps one SNS account secret from her family, she enjoys sharing the other with them.

"SNS improve our family's relationship because they generate convenient communication," she says.

"We should use it in a good way, rather than make it a barrier."

But generational differences manifest online. Youth typically document their lives on such SNS as WeChat, while older users often share links about street smarts, health tips and inspirational stories and quotes.

Yang Yunmeng's mother fits that bill. The daughter says: "The street smarts are based on rumors. The health tips are unsubstantiated. And the uplifting stories are meaningless.

"As a Virgo with obsessive compulsive disorder, I don't know whether to laugh or cry at Mom's posts. I can't tell her these things don't make sense."

But Yang Yunmeng believes it's her mother's right to share what she wants online. She realizes most parents want their kids to see their posts.

While some parents secretly spy on their children using fake accounts, some children sneakily tamper with their parents' actual accounts.

Often, the children set up their parents' accounts in the first place, so they know their passwords - or at least how to get them.

Yuan, the 16-year-old, started his mothers' accounts, so he knows her passwords - and uses them without her knowledge.

"If she posts something embarrassing about me on her micro blog, I'll log on her account and delete it," he says.

Yuan says his classmate's mother followed her boy's micro blog. The boy believed it was a classmate who admired him, since the posts were encouraging.

When he discovered the truth, he changed his mother's password and told her hackers had hijacked the account.

Such bait-and-switch tactics are commonly used by the younger generation.

Shanxi province native Ning Cuiming secretly added her 17-year-old nephew's QQ and WeChat to see if he had a puppy love relationship that could affect his studies. Upon discovering this, the boy unfriended his 49-year-old aunt on WeChat gave his QQ account to Ning's daughter. Ning didn't know about the switch for some time, and her daughter didn't realize until later why the boy had given her his account.

Ning says: "I just noticed he blocked me on WeChat. I'm very angry because he must have an ulterior motive."

Her nephew Ning Shaogang tells China Daily he did it because he needs privacy. Understanding and trust are the bases of communication, he says.

Lu Dan'ni, a 32-year-old primary school teacher in Guangdong province's Shantou, says: "The older generation doesn't have an awareness of privacy. They even had to report their marriages and divorces to service organizations and companies in the old days. It's easy to understand their actions if you know about their backgrounds."

While there are many distinctively Chinese contours to familial SNS relationships, the existence of such relationships is an international phenomenon.

US website Onlineeducation.net's survey found 92 percent of American parents on Facebook are their children's friends on the site. Half the parents say they joined the site to keep tabs on their kids.

And one in three teens on Facebook feel embarrassed by comments left by their parents, the survey finds. Comparably, 30 percent say they would unfriend their parents if they could.

Also, globally speaking, monitoring their children isn't the only reason parents start SNS accounts. Many enjoy their own social media lives.

Lu, the teacher, helped her 60-year-old mother Xie Yanying open a WeChat account because her mom was curious about the new technology and knew relatives her age were using it. Xie says it's also a great way to get news.

And Xu, the editor, often uses her micro blog for work, to share experiences and views, and communicate with colleagues.

She has continued using her micro blog long after her son - her original reason for getting her accounts - blocked her.

The mother and her boy, instead, discuss experiences and thoughts face-to-face, and share with others online.

And, they agree, that's the way they like it.

Contact the writer at xulin@chinadaily.com.cn

Tiffany Tan, Liao Mei and Lin Shutong contributed to this story.

(China Daily 09/15/2013 page1)