Village brings sunshine to prisoners' children

|

|

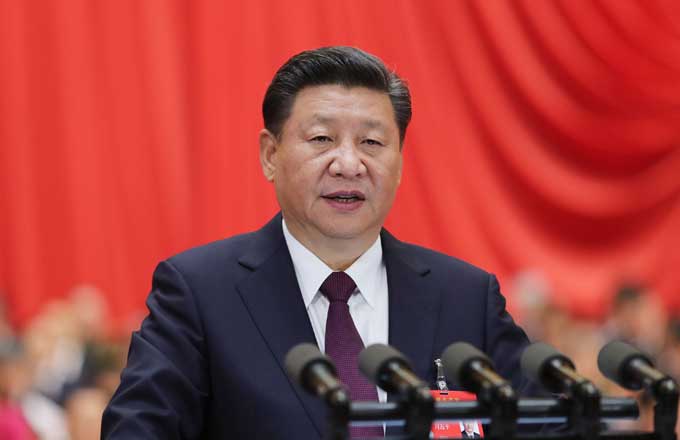

Zhang Shuqin, the founder of Sun Village for Special Children, works hard to provide a happy life for the children of convicts. Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

Zhang Shuqin is officially retired, but she rarely finds time to sit back and relax.

The founder of Sun Village for Special Children is a relentless fundraiser who is in equal part caring, committed and full of fight.

The 65-year old launched the center to look after children left alone when their parents were sent to prison. There are 1.5 million people in prison across the country but there is no government support for the children of convicts.

In many cases relatives take care of them, but some are unwilling to do so because of the stigma attached to criminals and, by extension, their children. "Chinese people have some traditional ideas that if a father is a criminal his son will be too," says Zhang.

The plight of abandoned children was highlighted in China recently by the case of two girls aged one and three who starved to death in a suburb of Nanjing under the supervision of their drug-addicted mother after their father had been sent to prison. One of the children had festering sores because her diaper had not been changed for so long.

"I have seen so many similar cases like this - children who have died or been orphaned because their parents were put in prison," says Zhang, who worked previously as a supervisor at a jail in Shaanxi province.

From one Sun Village, Zhang has expanded to nine such centers across China, which have cared for around 5,000 children since their inception in 1996. Currently around 500 children live in the villages.

The name Sun Village reflects Zhang's wish that the children should have happy childhoods, no different to others growing up with their parents.

"I wish every child living in Sun Village could be brought out of the shadows caused by their parents and grow up happily like the children of ordinary people," she says.

Zhang is motivated by a desire to see that the children are treated fairly by society and do not suffer because of their parent's actions.

She recalls nine-month-old Yang Yang - the youngest child cared for by Sun Village - with great fondness. His father was in prison for robbery and his mother had abandoned him because of the shame brought on by her husband's actions, according to Zhang.

"When I picked up the baby at the train station, Yang Yang was sleeping quietly in a policeman's arms," she says.

"He slept so soundly that he had no idea he'd been abandoned by his parents. The poor little thing, he had done nothing wrong but life had just been so unfair to him."

Yang Yang is now three years old and more than anything likes to be held.

"Actually, every child at Sun Village like people to hug them and hold them," says Zhang. "It is difficult for us, as they grow up without their parents' love."

Sun Village operates with the help of donations. The scheme's benefactors come from both China and abroad and include Shell, Nokia, Siemens, Hewlett-Packard and the Denmark Chamber of Commerce, as well as many individuals.

In 2006 Queen Silvia of Sweden, co-founder of the World Childhood Foundation, visited Sun Village, drawing media attention to the project.

While that initially seemed positive, it also put Zhang in the firing line for criticism, with some people claiming she was using the organization to earn money for herself.

A report in China Weekly said: "Zhang is actually quite a mature businesswoman who is full of ambition. Following her success in setting up the first Sun Village, she is expanding her business rapidly across the nation."

Zhang pays little attention to reports that talk about Sun Village as her business.

"I don't care about the doubts of society," she says.

"If no one set up Sun Village there would be no place to shelter these children. I believe I am doing something that no one else is doing in China."

The biggest question leveled at Zhang is over lack of financial transparency. But Zhang says such accusations are unfair.

"The outside world thinks I'm rich because I have received so many donations, but what we've got are goods and used stuff such as furniture and clothes," she says.

"Sometimes I even feel bitter when I have to ask for small things such as glue and staplers from outside."

One thing that cannot be questioned is Zhang's energy. Even during the interview she continued fund-raising for the Sun Village scheme, contacting a hotel owner who was donating blankets. "He was very warm-hearted and I'm wondering if I can find some job opportunities for the children through him," Zhang says.

Raising funds for the children's scheme has become more difficult since 2010 when a woman called Guo Meimei, who claimed to be working as a general manager for the Red Cross, posted photographs of her lavish lifestyle online. Although the Red Cross later denied she worked for the organization, the incident soured many Chinese against giving to charities.

To counter the added difficulty in securing funds, Zhang and other volunteers at the villages began planting their own fruits and vegetables, which are sold to provide funding.

"I am not afraid of the gossip that says I am running the charity in a commercial way," says Zhang. "We are already a disadvantaged group in society and need to develop ourselves to become strong so we can survive."