Foul air rises over landfill expansion

'Obnoxious projects'

The dispute over Tuen Mun is not the first environmental clash between the neighboring cities.

Daya Bay Nuclear Power Plant, which is in Shenzhen, has long been a controversial topic. When it was built in the 1980s, more than 1 million people in Hong Kong signed a petition protesting against the construction due to concerns over nuclear contamination and water pollution.

In 2010, there was further outcry in the SAR when it was reported a fuel tube at the plant had leaked. China Light & Power, a shareholder in the facility, confirmed in a statement there had been a small leak, but said it fell below international standards requiring them to report it as a safety issue.

More recently, on Aug 28, the Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department revealed a pollution case in July involving Ta Kwu Ling landfill, which is roughly 1 km from the Liantang suburbs of Shenzhen.

Sewage had leaked into the Shenzhen River, causing cross-border contamination, the authority said.

Chan Wan-sang, an outspoken opponent of the landfill expansions, is all for preventing further incidents, as well as further blights on his city's landscape.

"I have been against the landfills for the past nine years," said Chan, a district councilor in Tuen Mun for more than two decades.

He complained his area is already home to a power plant, landfill and steel factories. "The district has taken on too many obnoxious, polluting projects. It should not stand for any more," he said.

Tuen Mun used to have a low population and lots of free space, making it suitable for landfills. Yet the district has developed considerably, he said, not least because it faces Qianhai, Shenzhen's rising economic zone, while a customs base opened at Shenzhen Bay in 2007 now means a greater number of people pass through.

"When the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge is finished, I believe Tuen Mun's development will also speed up. So we have to preserve enough clean land for the future," Chan said. "A landfill expansion will be expensive and unfriendly to the environment, and the land will not be much use after it is eventually closed."

However, in August, a poll by the University of Hong Kong's Public Opinion Programme of 1,000 people citywide discovered 57 percent were in support of the expansion plans. Only 19 percent objected.

Incineration switch

Although the expansion plan is on hold, Hong Kong still faces the question of what it will do when its remaining landfills are completely full, which could be a reality in the next two to six years.

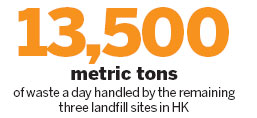

The three sites handle 13,500 metric tons of waste a day, according to the Environmental Protection Department. This includes roughly 6,000 tons of household waste, more than half of it food, plus 3,400 tons of construction waste, and 1,000 tons of dewatered sludge.

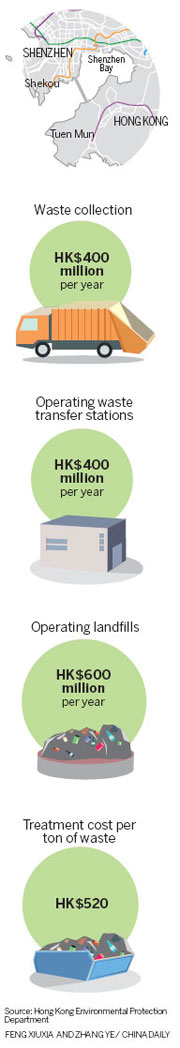

To collect, transfer and treat the waste and the run landfills costs the city about HK$1.4 billion ($180 million) a year.

For some people, including Shenzhen environmentalist Ao, the answer to the impending trash crisis is incinerators, such as those in Japan and South Korea that incorporate biofuel technology.

"Incineration can reduce the volume of waste by 80 percent. Plus, there's not much of a hazardous impact, and they can also be used to generate electricity," he said. "Hong Kong should shift its attention from landfills to incineration and build more sites, to reduce waste transport costs and secondary pollution."

After a study in 2007 and 2008, the Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department identified two sites suitable for the SAR's first waste incinerator, at Tuen Mun district's Tsang Tsui Ash Lagoons and the artificial island near Shek Kwu Chau, southwest of Hong Kong.

Going on further feasibility and environmental impact tests, authorities chose the island and eventually announced plans for a facility that will handle 3,000 tons of waste a day.

However, construction cannot start until 2014 due to the legal procedures and safety requirements related to transporting waste via ship, meaning it will be some time before the incinerator can go into action.

Faced with data suggesting that the Tseung Kwan O landfill will be full by 2016 and the one at Tuen Mun by 2019, city officials proposed making more room at existing sites to take the strain.

Chan, the district councilor, said he recognizes the need to expand the landfill while work continues on the incinerator, but he insisted any plan must include a size limit and a clear timetable for closure.

"Not every district in Hong Kong is suitable for a landfill," he said. "The plan is only acceptable to us as long as it is kept to within 100 hectares and comes with a commitment to close the Tuen Mun landfill when the incineration starts operation."

Shenzhen's environment commission and the Nanshan district environmental protection bureau declined to comment about the expansion plan.

Residents close to Shenzhen Bay, however, have been vocal in expressing their anger and opposition to the proposal.

"Environmental protection is a global issue," said Zhang Yunkun, who lives in Shekou. "You can't do harm to your neighbor just to benefit yourself. It's irresponsible and selfish for Hong Kong to build a landfill near a community."

He has complained about the air pollution to the Nanshan authorities, but the 56-year-old said he has so far received no feedback.

The Tuen Mun landfill should be closed for good, he said, warning that it could even hamper the progress in developing Qianhai into a financial services zone.

"When the Daya Bay Nuclear Power Plant was under construction, Hong Kong residents were informed. Now we want the same rights," Zhang said, adding that all residents deserve to be kept in the loop about projects that may affect them.

Chan conceded there have been misunderstandings in the past, and that his government should have discussed its plans with people in Shenzhen.

"Two regions share the same bay. Mutual respect is very important," he said.