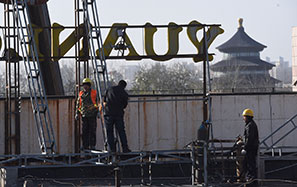

Laws bring reduction in forced demolition

|

People watch a house being demolished in Wenling cityk, Zhejiang province, after its owner reached an agreement with the local government. [For China Daily] |

New rules help keep violent incidents and confrontations in check, Tang Yue reports in Beijing.

For years, journalist Chen Baocheng wrote about other people's lives, covering stories on the judiciary and law enforcement issues.

However, the 34-year-old recently found himself in the headlines. In August, the Beijing reporter was briefly detained for allegedly holding a man against his will for a day during a protest over forced home demolitions in Chen's hometown of Pingdu, Shandong province.

Police claimed that Chen and a number of his fellow villagers had poured several bottles of gasoline over the man, a construction worker, and threatened to set him on fire. Chen was formally arrested last month, but as yet it is unclear whether he will face trial.

The story became a hot topic on Chinese social media. One observer, Li Gang, was more interested than the average news follower because the case reminded him of his own experiences.

Li, who is the same age as Chen, is also a reporter, but in Shanghai. Three years ago, his family home in Kaiyuan, Liaoning province, was demolished and the adjoining farmland was reclaimed by the local government without the family's consent. The move followed a three-year stalemate over compensation, Li said.

"One day they (the demolition team) just broke in early in the morning and drove my mother and my grandfather away from the house. I was in Shanghai and the news worried me greatly," he said.

"The government held my mother and grandfather in a hotel for a couple of days, until the officials were certain they wouldn't do anything extreme, such as setting themselves on fire."

When he heard the news, Li immediately joined a group of fellow villagers and traveled to a number of petition offices in Beijing. His mother went to Shenyang, the provincial capital, and moved in with her daughter and son-in-law, while his grandfather went to a nursing home, where he died last year at the age of 92.

Age of urbanization

The large-scale demolition of housing started in the early 1990s. Initially, old and shabby city dwellings were targeted, but as China embraced the age of rapid urbanization, the policy was soon expanded to include rural areas.

The process has reshaped the image of the country and the lives of its people, cleaning up the urban landscape and improving housing conditions for hundreds of millions.

|

Some residents still remain at Qutun village in Zhejiang province. They are asking fro more reasonable compensation. [For China Daily] |

However, in a country where local governments' dependency on land sales, house prices and people's awareness of their rights are all on the increase, the practice has never run smoothly.

Land sales have become an increasingly important source of revenue for local governments, rising from 9.19 percent in 1999 to 63.7 percent in 2011, according to the China Land and Resources Yearbook.

At the same time, forced demolitions have become a major source of social conflict; more than 22 percent of the mass incidents seen in China last year resulted from land acquisition and forced demolition, according to Legal Daily.

In 2009, a report by China News Service claimed that 40 percent of the cases received by the State Bureau for Letters and Calls, also known as the National Petition Office, from 2003-06 were related to forced demolitions.

The practice has given rise to an emerging phenomenon and coined a new phrase, the "nail house", which refers to people who refuse to move, for whatever reason, and whose houses stand out in an otherwise deserted and barren landscape.