"Some were concerned that granting couples two children would see the situation get out of control," said Feng Caishan, then deputy head of Longhua township.

The pilot program stated women could not marry until they were 23 and men 25, and women could have the first child no younger than 24 and the second no younger than 30.

Family planning officials said allowing couples two children has made their work easier, despite there being more procedures.

To ensure the program had the desired effect, women must have contraceptive coils fitted after their first child and must be sterilized after their second.

"We had a lot more work to do, as we had to convince people to have operations after the birth of each child," Wang said. "But importantly the policy is workable because people are willing to cooperate."

In 2007, the county further loosened the birth policies and women could have their second baby no later than 28 years old.

"From the experience in Yicheng we can tell that when the policy goes against the will of people, the people will oppose it," said Feng Caishan, who became director of family planning for the county in 1990 and retired in 2002. "The policy should take the statistics into account, and people's feelings," he added.

Changing attitudes

Looking at the figures, the pilot was a success in effectively controlling population growth. Yicheng accounted for 1 percent of the population in Shanxi in 1982, but just 0.87 percent in 2010.

Meanwhile, in many neighboring counties, the family planning policy has faced a backlash. Some couples are even giving birth to three or four children, according to an official with the Yicheng Family Planning Association who spoke on condition of anonymity. The China Family Planning Association is the largest nongovernmental network active in reproductive health, family planning and HIV/AIDS prevention and care.

Despite being given the chance to have two children, more than 10,000 rural families in Yicheng have chosen to waive the right.

Liang Zhongtang, the initiator of the program, said he believes important factors lie in the changing concept of fertility since the 1980s.

|

SHAN JUAN: REPORTER’S LOG Family policy is changing but not ending A farewell to the family planning policy? Not so fast. More than 30 years after China issued its unique policy limiting most couples to just one child, along came November 2013 and a new, relaxed rule allowing couples to have a second baby if one of the parents is an only child. As an only child born in the 1980s who is part of China’s first generation under the old rule, I have always been fascinated by even the slightest policy changes. The seeds of that fascination sprouted in my childhood when I visited my uncle in the countryside. The ubiquitous white-ink slogans plastered around the village read something like this: “Raise fewer babies but more piggies” and (worse) “Houses toppled, cows confiscated, if abortion demand rejected.” When I got into middle school, I was told by my mother that I could have two children in the future, provided the man I married happened to be an only child like me. After graduation from college, I entered journalism, and I now cover health and population issues. It’s on my daily working list to closely follow the “fine-tuning” of the birth rule, which the country’s top leadership said at the start would last for a generation, or 30 years. Did they keep the promise? I’ve been told yes. Of course, a couple may choose to limit themselves to just one child — and that appears to be the trend in the era of economic growth and urbanization. But at least a limit of one will not be forced by government policy in most cases. Starting in the 1990s, the initial policy was relaxed, and couples were allowed to have a second baby if each parent was an only child. In November, the rule was further relaxed so that just one parent need be in that category. The new rule will go into effect next year. Here I sigh deeply. In my case it’s my own fault if I can’t have two babies. I am in my early 30s, and I have no child. Seemingly, I must rush to put aside everything else to achieve two pregnancies while I am yet in my reproductive prime. Otherwise, I will face risks as an “old” expectant mother — the possibility of premature delivery, placental abruption or easy miscarriage. After a twist of mind, I decided to have just one child, but I still appreciate the policy change. To my way of thinking, family planning should always be done by and within families. Now, we are told, more couples can have two. But you are still a violator if you have three. So the policy doesn’t stop. It’s just changing —for the better, of course — but not ending. Maybe more people will tend to have small families. But the choice should be up to them, rather than imposed by any government rules. Contact the writer at shanjuan@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Feng, the former head of the county's family planning bureau, added: "If people live in an agricultural culture, it is natural for them to have more children as farm work requires more hands. That's why they prefer boys over girls. "Now, against a background of industrialization and urbanization, it is natural that people will choose to have fewer children."

In Beiye village, 14 of its 17 couples have decided to give up their right to have a second child and take the certificate for supporting the one-child policy after giving birth to their first, according to Xu Hongmiao, a family planning worker.

Wei Hongli and her husband, Yang Wenquan, decided to stop at one child after the birth of their son in 1998.

"The cost of living is so high," the 36-year-old mother said. "I can't imagine what our living conditions would be like if we have a second child."

Sun Ruisheng in Taiyuan contributed to this story.

Changes could balance gender ratio

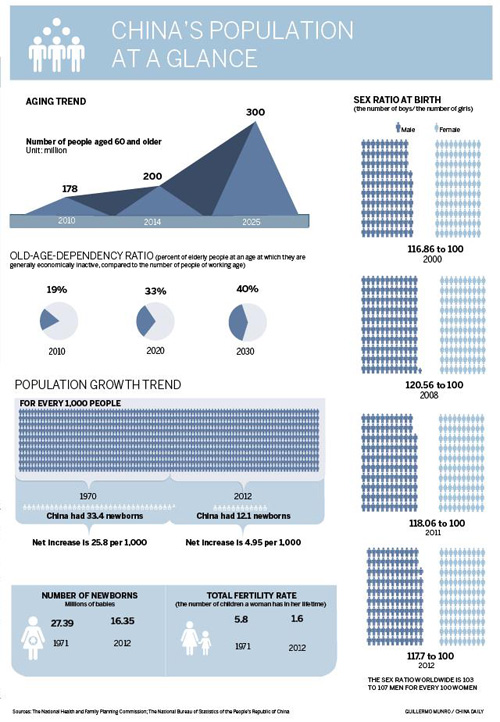

Demographics in three areas where the rural two-child policy has been tested indicate that allowing couples to have two children could result in an increased fertility rate and a more balanced gender ratio.

In addition to Yicheng in Shanxi province, trials have been carried out in Jiuquan, Gansu province; Chengde, Hebei province; and Enshi Tujia and Miao autonomous prefecture in Hubei province, with rural couples able to have a second child since the 1980s.

Despite the implementation of the policy, the population growth rates of Chengde and Enshi were lower than national census figures between 2000 and 2010.

The number of residents in Chengde grew by 3.42 percent over that period, lower than the national growth rate of 5.84 percent.

In Enshi, the population decreased by 12 percent, as a result of the outflow of migrant workers, a study by demographer Yi Fuxian showed.

The population of Jiuquan, which implemented the policy in 1984, grew higher than the national average to 11.8 percent between 2000 and 2010, as the city's sixth population census showed.

According to Yi's study, the two-child policy in those areas improved the fertility rate, which measures the average number of children a woman gives birth to in her lifetime.

"In 2000 the rate in Chengde was 1.36, higher than the 1.29 for Hebei. In Enshi, the figure in 2000 was 1.36, higher than the 1.01 for Hubei," he told Caixin Magazine.

His study also found the policy was able to significantly balance the gender ratio.

In 2010, the ratio for children aged 1 to 4 was 110 boys for every 100 girls in Enshi, lower than that of Hubei province for that year, which was 124 boys for every 100 girls.

The ratio for ages 1 to 4 in Chengde and Jiuquan in 2010 — 114 boys for every 100 girls — was also significantly lower than that of provincial areas, Yi said.

One of the major problems brought about by the one-child policy is the imbalance of sex ratio at birth, as the 2010 national census showed China has a 118 boys born to every 100 girls.

However, Yi warned that the two-child policy could not provide a fundamental solution to the imbalance in sex ratio even though the chances of selective abortion would be reduced greatly.

"If couples were only allowed to have one child, half of all families would give birth to boys. If they were allowed to have two, three quarters of families would get at least one boy," he said. "There would be much less motivation for selective abortion.

"Compared with the one-child policy, allowing couples to have two children would reduce the sex ratio at birth. However, there is still the problem of an imbalance in sex ratio, as the experiment indicated."

— XU WEi

xuwei@chinadaily.com.cn

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|