Remembering fellow heroes

By Zhao Xu (China Daily) Updated: 2014-11-12 08:13

|

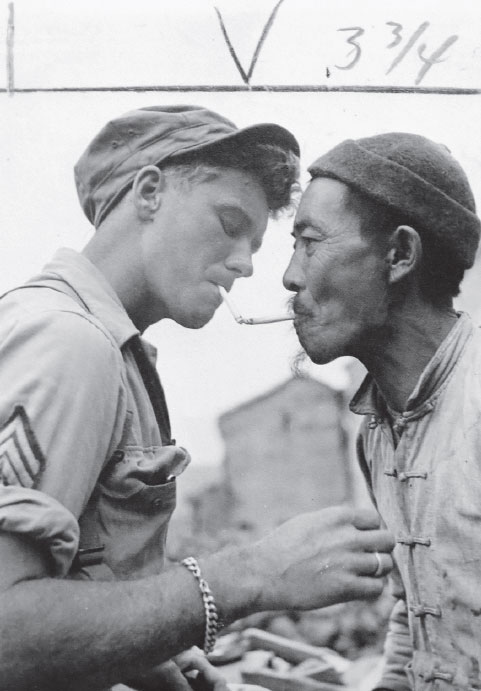

Taken on Oct 14, 1944, this picture from the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington shows a Chinese man on the streets of a bomb-shattered Tengchong in Southwest China's Yunnan province getting a light for his cigarette from a US Army sergeant. Provided to China Daily |

Researchers help shed new light on precious parts of shared WWII history between China and US allies, as Zhao Xu reports.

Barbara McMurrey, a 73-year-old from Texas in the United States, believes that her father, Major William McMurrey, still has a guiding hand on her, 70 years after his death.

"I was three when he was killed in 1944, during a fierce battle with the Japanese on the southwestern border of China," she said.

|

|

Major William McMurrey (1910-1944) |

"Keeping the grief and memory to herself, my mother had very seldom discussed the man with her two children. For me, Father was just a name, a black-and-white picture, a distant figure forever shrouded in the misty, gauzy sheets of rain that had poured nonstop on that strange land more than half a century ago."

That was until about a decade ago, when Barbara had an early-morning dream.

"Unrolled before my mind's eye was a countryside view in the Orient," she said.

"Slightly bewildered, I saw a man with a buffalo walking slowly towards me ..."

A few years later, in the summer of 2005, Barbara was invited for the first time to China by a group of Chinese field researchers who told her that they had found her father's original burial place. It was in Tengchong, a small farm county in Southwest China's Yunnan province. While trekking on its muddy mountain trail toward her destination, she suddenly spotted a local villager and a buffalo.

"It was a Motherent of revelation: I was led to that place by my father, who's never left us," she said.

Deng Kangyan, 56, an amateur historian-and-documentary film producer, had played a major role in bringing that revelation to Barbara.

"For me, it all started with a black-and-white picture, which I got from the son of a village doctor in Tengchong. The old man, who had long gone, treated injured soldiers - both the Chinese and Allied troops - during World War II while operating a small backroom photo studio," he said.

"Most of the films sent to him for developing were from the Allied officers who had cameras. And the man made an extra copy of those which he deemed important. This was one."

The picture depicts a funeral: Under the silent gaze of a group of uniformed-clad soldiers, both Chinese and foreigners, a wooden coffin was being lowered into the grave. A huge banyan tree stood right behind them.

"It was one of the countless sad Motherents during WWII, taking place in Yunnan, part of what was known then as the China-Burma-India Theater (CBI) of the war."

Between the outbreak of the Pacific War on Dec 7, 1941, and the Japanese surrender on Aug 15, 1945, the Allied forces, mostly the Americans and British, joined Chinese troops to fight the invading Japanese, under arguably the harshest conditions encountered by any army during the war.

"The inhospitable subtropical climate, the seemingly unstoppable monsoon-season rain, the onslaught of the forests bugs, the scrub typhus that had claimed many lives, the enemy troops who, faced with their ultimate defeat, had gone all but crazy - for anyone who had been through these, the CBI experiences were absolutely unique and unforgettable," said Ge Shuya, an authority on that part of wartime history.

Bernard Martin knows all about it firsthand. In late August, the 93-year-old flew from his home in the US to Beijing to participate in the opening ceremony of a photo exhibition commemorating the Allied effort at CBI. All the images come from the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, where Deng Kangyan and his team of seven had spent half a month in 2010 frantically recording everything that they could find related to China's WWII history, including photos and footage. The show was organized by the Shenzhen-based Yuezhong Museum of Historical Images.

While the machines of war roared in the background in the form of US airplanes and tanks, the overwhelming majority of the pictures on view spoke volumes about humanity. Combat personnel were caught in their non-combative Motherents, Motherents that revealed them as interesting and deeply interested humans ready to dive into a foreign culture.

A US sergeant was shown painting a watercolor of a tribal woman in the hills of Yunnan. In certain cases, feet were probably more nimble than fingers: The US soldiers, while outperforming their Chinese counterparts in an American football match, had found the mastery of chopsticks too daunting a challenge. In one particularly moving shot, taken on Oct 14, 1944, a Chinese man paused on the streets of a bomb-shattered Tengchong to obtain a light for his cigarette from a US Army sergeant.

All that does not mean war was less cruel than it sounds; in fact it was even more so, said Martin, who was delighted to discover his picture at the exhibition, one that showed him and a Chinese soldier inspecting each other's rifles near Nhpum in Burma.

"The Japanese got all the paths heavily guarded, so we chopped our own paths in the forests, with a hatchet. Remember: We were sneaky Americans," he said, with a mischievous smile.

"Once we raided a group of Japanese stationed in a Burmese village. There were around 800 of them and it was breakfast time. We came from their back. The Japanese, totally unaware of what's about to happen, were still in the river bathing: Some were completely naked while others were swathed in clothes," Martin said.

"We opened fire. The fighting continued for two hours and at the end of it, the bodies of the Japanese were floating down the blood-streaked river."

Martin, who called himself "a daredevil", belonged to the 5307th Composite Unit, whose 3,000 members were the only ground battle forces the US government had sent to CBI. A long-range penetration jungle warfare unit, it was more famously known as Merrill's Marauders, after its brigadier general, Frank Merrill. The general himself died in 1944, in the middle of the three-month-long battle for Myitkyina, a Burmese town-cum-airfield whose capture dealt a fatal blow to the Japanese army in Southeast Asia.

Martin took part in the battle but said he could not remember the walk to the airfield because "that's how beat we were after all that continuous walking and fighting. ... We arrived at the airstrip and started digging trenches. All of a sudden, all hell broke loose and a wall of lead from a thousand rifles came our way. I saw the officer who was with us go down and then I passed out."

It turned out that Martin had contracted scrub typhus, a problem that could have saved his life.