Education still a priority for parents

By Zhang Yi (China Daily) Updated: 2014-12-15 07:46Traditionally, Chinese parents have always zealously provided good education for their children, and the belief that "knowledge changes fate" is deeply rooted in the public psyche.

However, a vicious cycle operates in the world of education whereby students who don't attend good primary schools are unlikely to gain entry to a good high school, even if their performances are excellent, and the chances of going to a top university will be greatly reduced.

Most families in China still believe that a good university education is pivotal to securing a good job. Under the new policy, families without connections in the education authorities will also have the opportunity to give their children a good education.

Primary schools used to select students via a raft of enrolment policies, including household registration, exam results, and special dispensation for those who displayed talent in specific areas. Although admittance through exam results is seen as a popular selection method that takes no account of a student's family background or wealth, some parent claim the grading process lacks transparency and that corruption and cheating are commonplace.

The method has also been accused of raising levels of stress and anxiety among children, and critics say the long periods spent studying can also result in poor physical health and a lack of social and practical life skills among students.

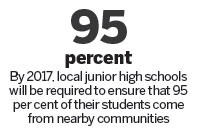

In April, the Beijing Municipal Education Commission ruled that primary school enrollment should be based entirely on the student's home address and proximity to a school, and strictly prohibited enrollment exams for primary schools.

The policy is intended to root out corruption and is expected to help reduce the number of parents who bribe officials to get their children into the best schools.

In the past, exploiting personal relationships was one of the most efficient ways for people to ensure their children attended a top school. "I had to switch off my cellphone during the application season last year because of the dozens of calls I received every day from people asking me to help get their children into the school," said the deputy head of a Beijing primary school, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

The new policy has drawn as much praise as criticism. The attempt to curb corruption has been applauded, even as critics complain that it will close the doors of good schools to students from regular families.

Zhang Lin, a public servant and the mother of a 5-year-old girl, said: "I have no way to raise enough money to even buy a 1-sq-m studio. My daughter is smart, and I would rather the authority continued with the enrollment policy based on exams. At least it gives every student an equal opportunity to access decent primary education."

Xian Lianping, head of the Beijing commission, said the department will step up its efforts to allocate good education resources across a number of different districts, which should help to reduce the number of parents who run into debt just so their children can attend a top-quality school.

He warned of the risks of buying properties near schools, and said the purchases are unlikely to have the desired result because of changes to Beijing's education districts that could see the school map redrawn in the coming years.

Schools' regulations may also negate the value of property purchases made in the hope they will secure entry to a good school. Jingshan primary school in downtown Beijing requires prospective students to have at least three years' hukou in the district before their parent can apply for entry. Meanwhile, in a bid to prohibit bogus registrations, Puti primary school in south Beijing's Fengtai district insists that students must share the same household registration as their parents or grandparents in the same education district as the school.

Despite the regulations, some parents will carry on regardless. "I would rather take the risk of buying a house close to a good school. The demand for houses near ideal schools is set to accelerate because of the baby boom that's likely to come in the next couple of years after the government eased the decades-old one-child policy last year." Li said.

- Govt encourages people to work 4.5 days a week

- Action to be taken as HIV cases among students rise

- Debate grows over reproductive rights

- Country's first bishop ordained in 3 years

- China builds Tibetan Buddhism academy in Chengdu

- Authorities require reporting of HIV infections at schools

- Typhoon Soudelor kills 14 in East China

- Police crack down on overseas gambling site

- Debate over death penalty for child traffickers goes on

- Beijing to tighten mail security for war anniversary