Not schools for scoundrels

By Peng Yining (China Daily) Updated: 2014-12-18 08:12

|

|

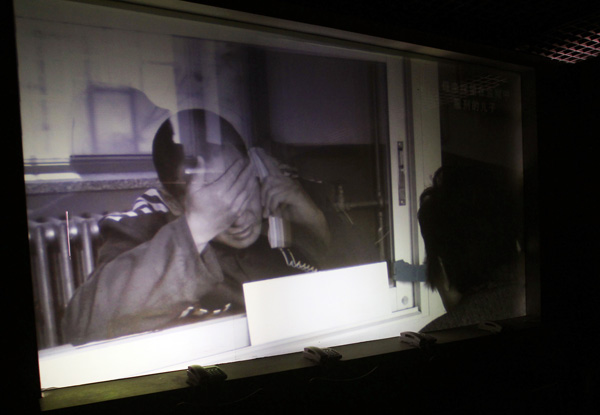

The Daxing Anti-Corruption Education Center in Beijing uses videos of convicted former officials as vivid warnings to visitors, as part of the government's crackdown on graft. Zou Hong / China Daily |

High-tech approach

Many of the centers have adopted high-tech display methods to ram their message home. In the Guangdong center, a movie theater equipped with a large circular screen and surround-sound audio shows footage of the media coverage of trials of corrupt officials. As the video ends, the mosaic of TV screens that make up the theater floor displays a sheet of ice that cracks under the feet of the audience, sending shards into a deep, dark hole. It's a none-too-subtle warning that being an official is like walking on thin ice, and any unlawful act could cause their downfall.

"The exhibition is very educational," Li Yiwei, the Party chief of Foshan city in Guangdong, said during a visit. "Every Communist Party official should pay a visit."

Li Jianguo, the head of a large petrochemical company, was shocked by an exhibition that featured Chen Tonghai, the former head of the China Petrochemical Corp, who was handed a suspended death sentence after being convicted of graft worth almost 200 million yuan.

"He used to come to my office. We even shook hands," Li said, shaken.

At one time, the center was only open to officials above the level of chu, civil servants of middle standing, but later ting, or section heads, were admitted too, and then ministers. Now, however, 70 percent of the visitors are lower-level officials and those outside the civil service but still in positions of authority, such as businesspeople and teachers.

Xue said the center wants to educate more people across a wider scale, and the impact it's made has prompted a number of anti-graft organizations, including the Independent Commission Against Corruption in Hong Kong, to arrange exchange trips.

In October, an education center in Huai'an city, Jiangsu province, opened a display about the methods of torture used in imperial China. It shows life-size mock-ups of prisoners being subjected to the infamous Tiger Bend - by which a prisoner's legs are broken slowly and painfully - burning, cutting, flaying, and being stretched on a rack.

This method of "education through warnings" is probably a Chinese invention, and has a long history, according to Du Zhizhou, deputy director of the Center for Integrity Research and Education at Beihang University, who said the method is one of the most effective forms of anti-graft education because the visiting officials can learn lessons by observing the treatment meted out to former colleagues.

"In 2007, I visited a center in Beijing, and came away feeling that it does shock visitors to some degree," he said. "But education only works in conjunction with an efficient anti-graft program and appropriate punishments. The influence education can have on the fight against corruption depends on the soundness of the system, and whether the punishments will deter potential offenders."

Du said education can reduce the urge to act corruptly, while the system reduces the opportunity for such behavior. When the opportunities for corruption are widespread, it's difficult for education to achieve the desired effect.

Although most of the comments in the guest book at the center in Guangzhou were positive, one anonymous visitor had written: "The tour wasn't just educational. It also prompted a series of questions, such as What's wrong with our Party officials? How were corrupt officials promoted and how did they gain power? Did the government test them? Why didn't the government supervise them? Why didn't the people supervise them?"

Contact the writer at pengyining@chinadaily.com.cn

- Beijing courting overseas tourists

- China pledges $3b investment fund for Central, East Europe

- China's 'saddest city' makes way for water diversion project

- Graft watchdog steps up SOE investigations

- Relocated parents face hard lessons

- China's Xi receives highest rating among world leaders

- Beijing wins central approval for new international airport

- Chinese New Year's Eve resumed as holiday

- China demotes 1,000 'naked' officials

- Family of wrongly killed man may get $193,860: media