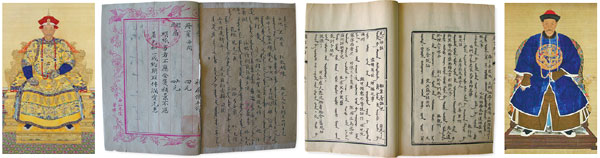

Manchu a window into forgotten past

By Zhao Xu (China Daily) Updated: 2015-04-03 07:32

|

|

Spike in interest

Insinuating itself into Mandarin had once ensured the survival of Manchu, at least in parts, yet in an era when a global culture is taking hold at the price of local flavors, its demise seems more or less inevitable, at least to Tong.

"Surveys in the 1950s of people living in a remote Manchu village in northeastern China found most people older than 60 could not only understand but also speak Manchu," he said. "Most people between 60 and 40 could understand but speak very little, while most people between 40 and 20 could only understand the language.

"People in their 20s back then are today in their 80s and 90s. If anything, they offer an apt metaphor for the fate of the language.

"These days," he added, "if you go to one or two very secluded villages in far northeastern China you may still encounter elderly people who speak Manchu, especially when they gossip."

In recent years, television shows dramatizing the court life of Qing emperors and their consorts have sparked an interest among young people in the history and language.

Some have even enrolled in Manchu courses taught by university students majoring in Qing history.

"I've met people who insisted on talking with me in Manchu. Frankly, this is pointless and impractical," Tong said. "During the early reign of the Qing, each year the central government would compile and publish a list of new Manchu words, translated from Mandarin, which was constantly expanding. Not adhering to this list was a crime.

"Today, no such effort toward standardization exists. It effectively means people have to do their own translations when a new word pops up, which happens frequently. The result is conflicted expressions and blocked communication."

Rather than resuscitating the language, Tong said the biggest benefit of studying Manchu is rediscovering lost memories of the past.

Yan agreed. "Knowing the language has given me a unique, titillating and often tragic peek into history," said the 81-year-old, referring to his findings concerning the history of the royal mansion in suburban Beijing.

Emperor Kangxi ordered its construction for his seventh son, born to his first queen, who died hours after childbirth. Bereaved, the emperor made this son - Yinreng - his legal successor when he was merely 1 year old, only to have him banished when he was 34, reestablished a few years later, and then banished again, sealing his fate one last time.

An intense political struggle is blamed for driving a deadly wedge between a doting father and a son whose early achievement is said to have threatened even his all-powerful father.

Fully aware that Yinreng, like any fallen crown prince, would have to spend the rest of his life in confinement, the emperor built the Beijing compound, which was completed a year before his death at the age of 69.

"Usually, a confined prince would die at the palace," Yan explained. "My guess is the emperor deliberately chose a rather isolated place on the fringe of the capital, to allow his son more comfort and freedom. A heartbroken father and a heartless ruler, Kangxi was both."

Yinreng died three years later in 1725, aged 51, and never lived in the home his father prepared for him, although his son did.

Emperor Qianlong demolished the mansion in about 1740 when he decided it was safer for the descendants of his long-perished uncle to live under his direct watch, near the city center.

"But that's another story," Yan said.

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

- Govt encourages people to work 4.5 days a week

- Action to be taken as HIV cases among students rise

- Debate grows over reproductive rights

- Country's first bishop ordained in 3 years

- China builds Tibetan Buddhism academy in Chengdu

- Authorities require reporting of HIV infections at schools

- Typhoon Soudelor kills 14 in East China

- Police crack down on overseas gambling site

- Debate over death penalty for child traffickers goes on

- Beijing to tighten mail security for war anniversary