Cliffhanger for climbing 'cradle'

By Xin Dingding and Huo Yan (China Daily) Updated: 2015-07-31 07:45

|

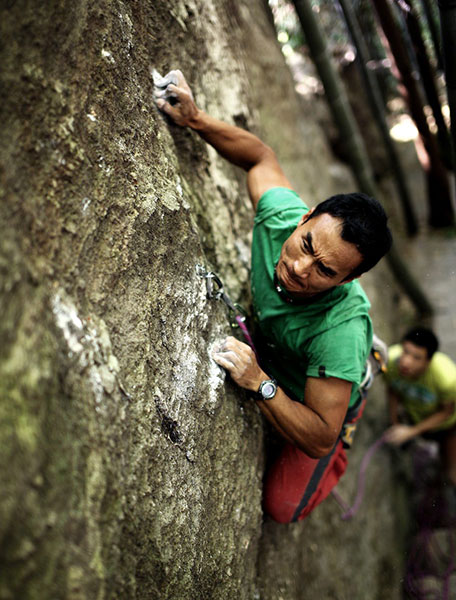

Zhang Yong climbs a face on Laoshan Mountain in Qingdao, Shandong province, in 2013. Zhao Si / for China Daily |

Ding, who headed the CMA's climbing department for 16 years, said China has several climbing centers - including Miyun and Fangshan counties in Beijing, Ziyungetu in Guizhou province, Xinxiang in Henan province, and Kunming in Yunnan province - but Yangshuo is the only one with a fully developed climbing industry and a lot of local support.

Zhang underscored that view: "When you ask a farmer around here what climbing is, they can tell you. But if you ask the same question in Northeast China, the locals won't know."

Sadly, that local knowledge has occasionally led to friction. When the villagers saw the revenue local climbing clubs were generating on the barren rock faces, some of them decided they wanted a slice of the action.

In 2010, some tenant farmers began charging climbers for passage across their land. However, many climbers were unwilling to pay, which resulted in heated arguments and sometimes even physical violence. Some people threatened to cut the climbers' ropes or impound their equipment, bags or bikes. Eventually, the local authorities advised climbers to pay the farmers to avoid potential flashpoints.

Liu Yongbang, a top-flight Chinese climber who runs his own club, said he pays villagers when he organizes commercial activities in their area. "But there are more problems than that. Every year they ask a higher price, although we're just passing through their land," he said, adding that he has appealed unsuccessfully to the government to make a ruling on the issue.

"The government won't speak up for us. It doesn't object to us climbing, but it doesn't support us, either. After all, the climbing industry can't generate as much revenue as tourism. There's a big difference between the millions of tourists who visit Yangshuo, and the thousands of climbers who come here," he said. "Also, the government thinks climbing is dangerous and could cause problems. We have to solve the problem by ourselves, and open more new routes on new sites," he said.

The classic routes on Moon Hill, the cradle of Yangshuo's climbing industry, can never be replaced, though.

In 2013, a private company that has rented the hill and surrounding land banned climbing, citing the potential for fatal accidents.

Some enthusiasts simply ignore the ban, though, and last year, Zhang and some friends proposed replacing the aging bolts and carabiners fixed to Skinner's five classic routes, because the original equipment is badly worn and could pose a threat to the illegal climbers.

The group raised funds and spent more than 10,000 yuan ($1,600) on equipment. Armed with approval documents issued by the local government, Zhang and his team refurbished the equipment on two of the original routes.

"Later, we discovered that the new carabiners had been smashed by the company to stop people climbing, and we were forbidden to replace the equipment on the three other routes," he said.

He asked the county government to arbitrate on the matter, but the officials told him to negotiate with the company and solve the problem himself.

"Moon Hill was a place for climbing 23 years ago, long before it became a scenic spot. It's the birthplace of Chinese rock climbing and has five classic routes created by a legend. But now, climbing and other 'dangerous' outdoor activities have been banned. It's a really sad turn of events," he said.

Contact the writers through xindingding@chinadaily.com.cn

- Delegation salutes Tibet anniversary

- Officials are told to act as anti-graft watchdogs

- Great Wall safeguarded in united action

- Vice minister pledges more efforts to improve air quality

- Beijing’s efforts to control air pollution start to pay off

- China's military committed to reform

- Netizens rip singer over baby photos

- Central govt's growing support for Tibet

- Monument to be built on Tianjin blast site

- China and Russia seal raft of energy deals