Love and loss in war and peace

By Zhao Xu (China Daily) Updated: 2015-10-14 07:19

|

|

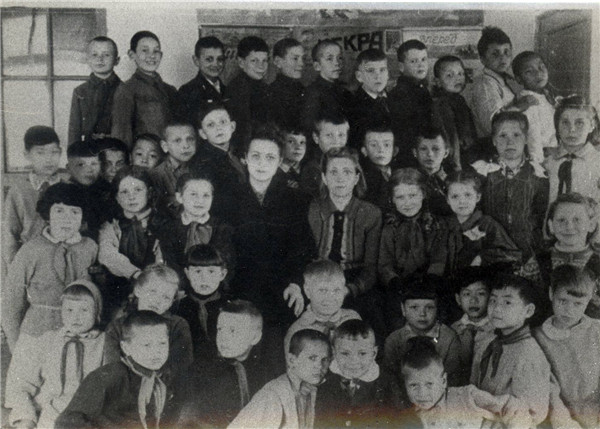

Children and teachers at the Ivanovo School. [Photo/China Daily] |

Tough existence

Li Duoli resorted to "stealing" to kill his hunger: "I 'stole' vegetables I'd planted months before-turnips and potatoes-in a plot maintained by the teachers and children," he said. "Once, I was caught red-handed by a slightly older boy who was tending the plot. He allowed me to leave with a lapful of turnips, but only after he'd given me a terrible dressing down. No outside supplies of food or coal were provided, but by plowing the icy land and collecting wood in the forests, we survived the long Russian winters."

Germany surrendered on May 9, 1945. Li Duoli was age 9, and he remembers VE Day as one when "we were allowed to eat as much chocolate as we could".

Life at Ivanovo was improving fast, and when Li Shuhua arrived at the school in 1947, he felt as though he was in heaven. "My parents left the Soviet Union that year. My father was suffering from a severe gastric illness, unable to work. They took my little sister, born in 1944, with them, leaving my younger brother and me behind in Ivanovo," he said. "I wasn't sad at all. For one thing, I'd never seen so much food before, nor had I ever seen so many Chinese. I made many friends, including Li Duoli."

There was also a lively cultural scene, according to Xiao Suhua, who spent nine years at Ivanovo. "Even before the war ended, a dance troupe was formed inside the orphanage by a woman who had received formal ballet training, but was unable to perform because of a hip injury," the 78-year-old former dancer said. "I was the only boy in the (full) troupe."

Li Duoli witnessed his classmate's early talent. "During the war, a school building was converted into a military hospital, and we performed for the injured soldiers to cheer them up. I was a backup dancer, but Xiao was always the lead."

After the war, Xiao's talent quickly made him a local celebrity, not just at the school, but also in the wider city, and he won municipal dancing competitions several years running. "In the winter of 1949, the Moscow Dance Academy came to the city to recruit new talent. My dance teacher organized a truck to take me to the place where the auditions were being held. I danced for the judges and they gave me the nod," Xiao said. "But I didn't go to the academy, because in 1950, almost all the Chinese children at the boarding school were asked to return home by the Chinese Government."

Homecoming

Acclimating to China was tougher than many of the children had envisaged, according to Li Shuhua, who, along with Li Duoli, was among 78 students repatriated to China. "After 11 days traveling by train, we arrived at the Chinese border and I was met by my mother. But in the days that followed, my excitement quickly gave way to boredom and anxiety because I didn't enjoy the Chinese food Mom prepared for me, nor understand a word of Chinese."

For the next few years, he shut himself off from reality and attended Russian schools on the Sino-Russian border. "I was 16, and still unable to speak Chinese. Eventually, my father became very angry with me and sent me to a primary school in my hometown. Embarrassingly, I was in the fourth grade," he said, adding that he had fully assimilated within a couple of years.

He studied Russian at Liaoning University and became a professional translator, working for Xinhua News Agency for more than two decades. "Those days in the former Soviet Union determined the course of my career," he said.

The same could be said for Xiao Suhua, whose missed opportunity to study at the prestigious academy in Moscow didn't prevent him from becoming a famous figure in the world of Chinese ballet. "I'm forever grateful to my teacher for the exposure to the arts she gave me at Ivanovo," he said. Now a professor at the Beijing Dance Academy, Xiao visited Moscow earlier this year to judge a national ballet competition. His flawless Russian surprised and delighted the audience.

"With government funding, I trained at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow in the late '80s. Since then, I've been to Russia again and again," he said. "'Golden' is the word I would use to describe my life there during the war. It's hard to believe, but that's how I genuinely feel. It was an age of innocence."

- Domestic hit 'Goodbye Mr. Loser' rules China's box office

- Child prodigy, with IQ of 146, stirs debate on how to teach him

- 14,528 Chinese pilgrims performed Hajj this year

- Former China work safety regulator expelled from Party

- 'Black banks' targeted in latest anti-graft crackdown

- Early harvest seen for Belt and Road

- Air cleaning effort pays off

- Govt to spend $22b on bringing 98% rural areas online by 2020

- Taiwan flight-transfer talks continue

- China vows to increase support for refugees