Change to ease drop in workforce

By Zheng Yangpeng (China Daily) Updated: 2015-11-27 07:52

|

|

Babysitters attend a training class in Fuyang, Anhui province, in November. The babycare business is becoming an increasingly hot sector in China since the country proposed putting an end to the decades-old "one-child" family planning policy in late October. Wang Biao / for China Daily |

Researchers worry new births will prove 'too little and too late'

Employers and local governments don't need experts to tell them about the impact of the "one-child" family planning policy on the labor force.

Yao Linrong, a top official in the eastern city of Zhangjiagang, home of China's largest privately owned steel mills in Jiangsu province, knows exactly what the city government's greatest concern is for economic development in the next five years.

"It's population," Yao answered immediately. "We need a stable population to keep up our economy's growth momentum."

In southern Guangdong province and the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, an influx of Vietnamese and Lao workers is already making up for the shortage in workers.

Yet many experts have lamented that the change might be "too little and too late", as years of indoctrination on the virtue of fewer kids, and the increasing costs of raising a child, have cut women's penchant for more children.

"It will hardly have a major long-term effect on population growth in China, where many women are now more concerned about jobs and careers than is reconcilable with having a large family," said Patrick Gerland, a demographer with the UN population division.

Illustrating the point, the Chinese government since 2014 has allowed couples in which one is an only child to have a second child, but the effect has not been overwhelming. Of the 11 million couples eligible to have a second child, only 1.45 million applied last year. Fitch Ratings said China's new two-child policy cannot avert pressure on the population over the next 20 years.

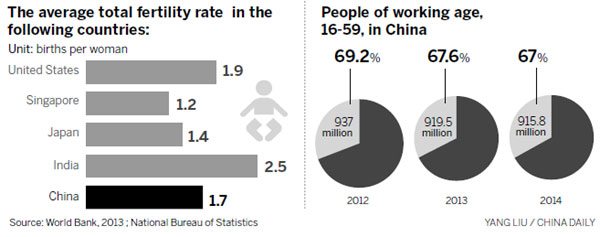

By the end of 2014, people aged 14 or younger made up 16.5 percent of the population - in 2000 the ratio was 22.8 percent. The country's total fertility rate - the average number of children born to a woman in her lifetime - has fallen to 1.7, well below the 2.1 level that is considered necessary to maintain the size of a population. If that rate is sustained, China's population will shrink by 36 percent in a generation.

That is sufficient to worry demographers and economists, who at least 10 years ago began to call for the abolition of the one-child policy, which had been in place since 1979. They argued that the demographic shift, namely the peaking of the working-age population, would shrink the supply of labor, dampen consumption and undercut investment, thus lowering China's potential rate of GDP growth.

Cai Fang, vice-president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a prominent demographer in China, long argued that the demographic change has reduced the country's potential growth rate during 2016-20 to 6.2 percent.

Ai Jingwei, a Shanghai-based commentator who has done research on China's demographics and its impact on the housing market, estimates the policy change could lead to another 1 to 2 million births a year. Still, the number of people between the ages of 25 to 49 years old, the prime home-buying group, will peak this year at 586 million people and will decline from next year onward.

Equity analysts are also excitedly discussing how the change might affect the baby food, diaper, toys, entertainment, healthcare and child-education sectors.

"Better late than never", Goldman Sachs' macro research team wrote after the announcement. "One may argue this move is too little too late ... But a broad based relaxation is surely better late than never and some people still want to have more than one child but cannot, especially those working in the public sector," they said.

zhengyangpeng@chinadaily.com.cn

- Xi urges breakthroughs in military structural reform

- Famous panda to celebrate 35th birthday

- Change to ease drop in workforce

- Plan predicts only 10 percent of Beijing seniors will need nursing home care

- 'Falls' one of top causes of death for Chinese men: Lancet

- 91 suspects repatriated in past year

- Govt move to Tongzhou set for 2017

- Reforms may end 20-year legal fight

- University officials punished for extravagance

- Largest coal mine identified in east China