Throwing money down the drain?

By Zheng Jinran (China Daily) Updated: 2015-12-10 07:59

A 'misplaced resource'

Sewage sludge is often called a "misplaced resource", because when treated correctly and rendered completely harmless, it can be utilized as a fuel, compost or fertilizer. That isn't happening, though, according to Cao Yanjin, a researcher with the Sewage and Sludge Management Bureau at the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development.

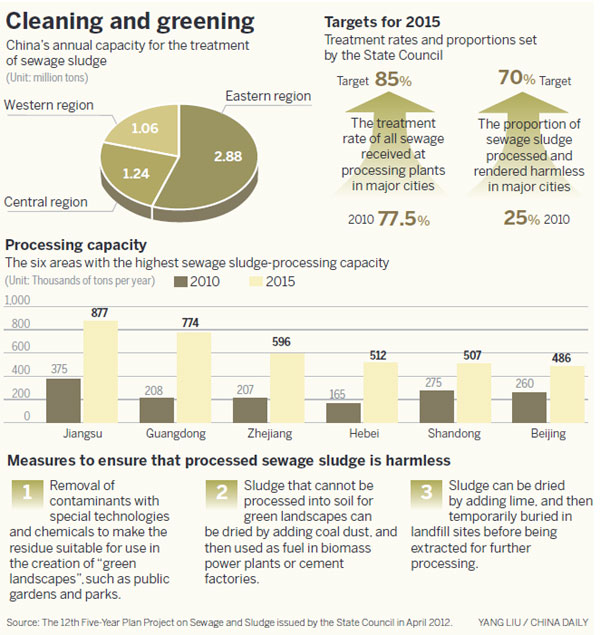

In the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-15) on sewage and sludge management, released in 2010, the State Council listed a number of ways of making sludge environmentally harmless.

Of the three leading processes, the most-effective and most-recommended method is to remove the toxic contaminants and make the sludge suitable for use as soil in public gardens and parks.

The two other major solutions involve drying the sludge by adding coal dust and then using it as fuel, or employing a simple dehydration process to reduce the water content by about 80 percent and then burying the material in landfills.

"No matter whether it's used as recycled soil for public gardens or burned in plants, sewage sludge could be utilized more effectively, and that would reduce pollution greatly," Cao said, adding that the utilization rate of sewage sludge as a resource is disappointing low.

This year, a survey by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development found that 56 percent of the country's sewage sludge is treated to eradicate toxic elements, and make it suitable for use as fuel or compost, or for burial.

The same figure was quoted by Chen, the minister, but a market analysis report by E20 Policy and Market Research, a think tank focused on domestic sludge, said the percentage had been overestimated. According to E20's annual report for 2014, only 10 percent of the sewage sludge was composted for use in public gardens.

The current treatment rate is far too low to allow local governments to achieve the targets set by the State Council in the 12th Five-Year Plan, which aimed for the proportion of sludge rendered harmless in major cities to rise to 70 percent by the end of the year, from 25 percent in 2010.

Cao said more than half of China's provinces have slow, unwieldy treatment processes, which makes it impossible for them to reach the targets.

- Psychiatrist links smog, depression

- Weather a bonanza for taxi services

- Lawyer: Top court OKs death sentence in poisoning case

- Power for ministries to be clarified

- Red alert helps to reduce pollutants, say experts

- Elderly people snapping up dance products online

- Aging population could shrink workforce by 10% in China

- Severe smog brings mask panic buying

- Foreign economists advise on blueprint for next five years

- Online searches spike for masks, purifiers, condoms and sportswear