Monopolistic media got social

By Peng Yining (China Daily) Updated: 2016-05-30 17:07Even as the entertainment improved, TV sets became cheaper and communal viewing became a thing of the past as people bought their own sets.

"I miss the days when people were closer physically, Dong says.

However, Li Heyang, 74, of Beijing, a former high school physics teacher, says new media can bring people together, too, even in a different way.

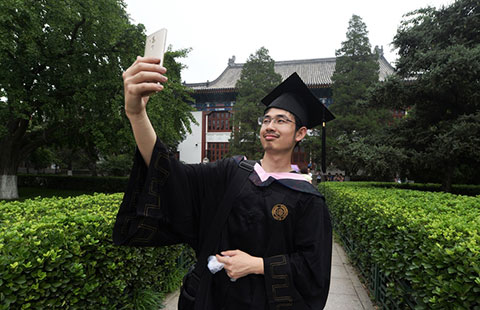

Li is the oldest member of a smartphone class for seniors his community has organized that has taught more than 200 elderly people how to access the internet using a phone and how to use apps to send and receive messages.

"I lost contact with many colleagues and friends when I retired," Li says. "At my age it is difficult to travel, but the smartphone brings us closer together. Young people are using smartphones to post microblogs, news reports and to book train tickets. I don't want to be left behind."

Li, born in a poor village in Jiangsu province, says that when he was 10 he used to listen to the radio while threshing wheat.

The only loud speaker in his village was installed at the top of a high pole outside, looking over Li and his fellow laborers.

"Most of it was political news, and it was all very solemn, echoing above our heads as we worked away.

"I read People's Daily and I talked with my classmates; I wanted to know what was going on in the world. I wanted to find answers, but in vain. What an individual could know at the time was very limited."

Nevertheless, newspapers were precious resources, he says. After dropping out of college because of the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976), Li says, he had the chance to resume his education at Peking University after the movement ended. But that opportunity was lost because the high school in rural Tianjin where he worked did not subscribe to the newspaper that carried the news of the movement's end.

"Isn't it bizarre how a lack of information can change a person's life? But that is exactly what happened to me then," Li says.

"You need information to stay connected with society."

- Flight-tests check routes to Nansha airfields

- Premier to set new course in Mongolia

- Copyright violators to be placed on blacklist

- Car-hailing firm bans mentally ill, criminals from driving

- Calling it quits: Divorce rate jumps 6%

- More rain to create Yangtze flood control pressure

- China condemns S Sudan attack that killed 2 peacekeepers

- National digital platform set up for volunteer services

- Typhoon Nepartak leaves six dead, eight missing in east China

- Fifth lighthouse to shine on S China Sea