Reliving the lives and times of Chinese immigrants

By Zhao Xu (China Daily) Updated: 2016-09-10 07:17

|

|

The Chinese Heritage Center at Singapore's Nanyang Technological University offers a glimpse into the everyday struggles of migrants from the mainland

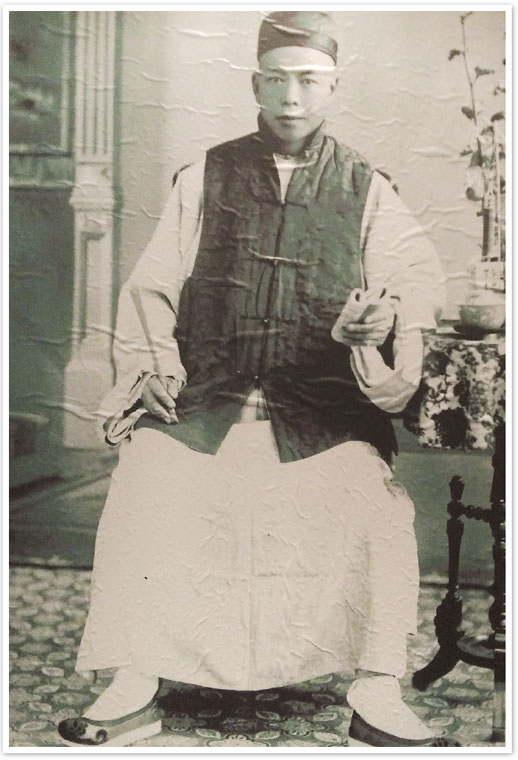

For Sophia Soon, a Singapore-born museum guide, a black-and-white picture taken of a Chinese man - probably a first-generation immigrant - and now hanging on the wall of the Chinese Heritage Center at Singapore's Nanyang Technological University, speaks volumes. "Look at his shoes - so small that he could barely squeeze his feet in," she says.

"They were actually props borrowed from a photo studio - just like the cheongsam and the hat."

"However, he was adamant about having this picture taken, where he was portrayed as a man of learning, evidenced by the book in his hand. Why? Because traditional Chinese culture valued literary achievements above all else," the 60-year-old says.

For those familiar with history, the picture holds up a mirror to generations of Chinese immigrants who traveled to Singapore, the reality of their existence, and the stubbornness with which they tried to hold on to their identity, while being constantly washed by the cultural tides flooding Singapore's shores.

"The Chinese first arrived in Singapore around the early 15th century. But the biggest inflow of Chinese immigrants in Singapore's contemporary history took place between the late 19th and early 20th century, when China was facing foreign invasion and political unrest," says Soon.

"The story of these immigrants progressed on two parallel narrative lines: one was about settling down; and the other was about reaching back."

Chu Kin Fong, a licensed tour guide and third-generation Chinese immigrant, has made it her job to take visitors - especially from the Chinese mainland - to Chinatown in Singapore.

The area, in the southern part of the island, is where Chinese immigrants once congregated, on both sides of the Singapore River.

"The majority of them worked as porters. But some ran restaurants or barber's shops," says Chu.

Life was never easy, she says. In fact, Chinatown is also known locally as "niu-che-shui", meaning "ox-driven water cart".

In the old days, Chinese immigrants, with no fresh water to drink, used ox carts to ferry water from other parts of the island.

However, according to Chu, the hardships endured were in a way mitigated with the formation of associations, which were essentially mutual-help groups based on the area in China where the immigrants hailed from.

"The heads of these associations were also community leaders who took under their wings men from their hometowns," she says, pointing to the two-storey buildings in Chinatown that used to house these associations.

"These days, they have largely turned into venues for the study of traditional Chinese art and culture, opera and instrument-playing, for example," she says.

From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, Chinese immigrants in Singapore, especially affluent businessmen, concerned themselves with the fate of their "motherland".

They offered financial support first to topple the Qing Dynasty, China's last feudal rulers, and then to the Chinese fighting the invading Japanese between 1937 and 1945.

After the end of World War II and the founding of the People's Republic of China the focus shifted. Starting in the 1950s, some local Chinese community leaders advocated the setting up of a Chinese university.

Prominent among the leaders was Tan Lark Sye, a rubber tycoon.

The university that came into being, in 1955 was called Nanyang University, with Nanyang, or the South Sea, referring to southeast Asia that includes today's Singapore and Malaysia.

Speaking of the project, Soon says: "We have black-and-white pictures showing people from all walks of life - from tricycle-pullers to dance girls - donating for 'our university'.

"Nanyang was the pride of all Chinese in Singapore."

Today, Nanyang University, or Nantah as it's known in Cantonese, is the site of Singapore's Nanyang Technological University.

Nantah was merged with the University of Singapore to form the National University of Singapore in 1980.

English is now the official language of all universities in Singapore.

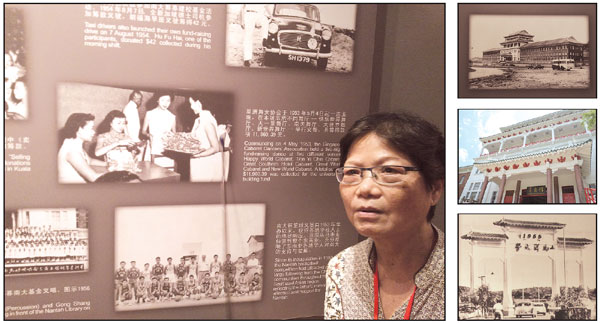

The Chinese Heritage Center is housed in the former administration building of Nanyang University.

The center, with a permanent display showcasing the history of Chinese immigrants to Singapore, is the only university research center outside China that specializes in the study of overseas Chinese.

That status is enhanced by a collection of 30,000 books donated by Professor Wang Gungwu, a renowned historian who is now the chairman of the East Asian Institute at the National University of Singapore.

The books, many on Chinese immigration, formed the core of the Wang Gungwu Library, located on the ground floor of the Heritage Center.

According to librarian Luo Biming, many books from the collection are very precious as they can no longer be found on the Chinese Mainland.

"Many were first published during China's Republican Era (1912-1949) but the copies were destroyed during the cultural revolution," he says, referring to the ideology-centered political movement that threw China into tumult between 1966 and 1976.

"In many cases, what we have is the only remaining copy."

Meanwhile, reflecting on the metamorphosis Chinese immigrants in Singapore underwent, both mentally and culturally, Soon points to a group of three pictures, of the same family taken over a period of 20 years.

In the first picture, everyone, from the matriarch who sits in the middle of the front row, to the younger members of the family, and even the toddlers, are dressed in traditional Chinese attire. The adults have long bead necklaces, then considered a part of court regalia.

Then changes gradually take place: the boys from the first picture appear in the second one as teenagers, and are dressed in Western-style suits that are too big for them.

If the second picture shows any sense of unease, the third picture portrays confidence, projected by the young men and women who have grown up.

Here, even the matriarch's son - the bread-earner of the family, had traded his heavily-embroidered Chinese official's gown for a sharply tailored suit.

His hair has turned white - thanks mostly to years of hard work to keep the family afloat.

One thing, however, remains unchanged: The matriarch and her daughter-in-law are still dressed in traditional style, years after their arrival in their adopted home.

"The women tended to be more conservative," says Soon.

"But even they had in time to yield to the need to localize."

The Republic of Singapore was founded in 1965.

And according to Luo the librarian, there were then efforts by the central government at "de-sinicization", in order to mint new a national identity, and to enhance social inclusion in a society that was - and still is - predominantly - ethnic Chinese, with Malays and Indians.

According to Luo, one can get a sense of the profound changes which took place in Singapore by comparing the textbooks used by school students before and after 1965.

"The notion of Singapore was stressed, as the emphasis shifted from Chinese history to local Singapore history," he says.

With this background, the picture of an early local cemetery for Chinese immigrants at the Heritage Center serves as a reminder of the country's contemporary history.

Inscribed on the gravestones are not only the names of the deceased, but also their place of origin, right from the province to the county and the village.

"In the back of their minds, they still wanted to go home," says Soon.

Born in Singapore, Soon is a second-generation immigrant.

"My father died in 1991, at the age of 79 and about 63 years after he took the life-threatening boat ride from the southern Chinese coast to Singapore," she says.

"Like most Chinese immigrants of his generation, dad, for many years, sent every penny he had earned and saved to China. In fact, he always longed to go back, but never did."

Weeks before the death of the old man, his son, Soon's brother, visited the family's home in China's Guangdong Province and managed to locate their father's elder sister."

"My brother took a picture of the old woman, our aunt, who was almost blind by then. Then, he returned to Singapore to show that picture to dad, who cried," says Soon.

"My father passed away a few days later, on October 1, China's National Day."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

|

|

|

The group of pictures, taken of the same family over more than two decades, show the gradual yet impossible-to-ignore changes undergone by early Chinese immigrants. |

- In visit to alma mater, Xi calls for equality

- China, US eye growth in tourism

- Space lab being made ready for launch

- 129 telefraud suspects sent to mainland

- Unified work permit for foreigners on way

- Zika unlikely to spread on mainland, officials say

- Exchange rates shaping travel plans

- Mental compensation stipulated in miscarriages of justice

- Center set up in Hainan to study fishermen's guidebooks

- Beijing setting up G20's first center to aid corruption fight