No happy ending for village matchmakers

|

|

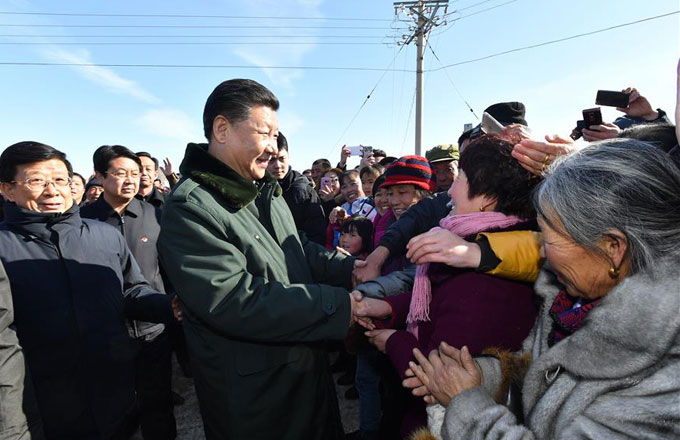

Zhang Kelan |

The month leading up to Chinese New Year has traditionally been the busiest for matchmakers like Zhang Kelan. But in recent years, business has not been so good.

This year, Zhang, 83, decided to call time on a career that has spanned half a century and seen her pair 104 couples, a record in her tiny village in Shandong province.

"All were happy marriages. Not a single divorce," she said, before attributing her success to her straightforward character, skillful handling of customs, and instinct to read the minds of parents.

Until the late 1970s, patriarchs in Chinese villages wielded considerable clout in deciding who their sons and daughters married. They would hire matchmakers to find the perfect match and smooth over the complicated customs, such as the dowry.

Zhang said it could take up to a year to go through the premarital customs: inquiries about names, the first meeting, further meetings, proposal and marriage. Even a small mistake could derail negotiations.

But that all sounds a bit last century. China's rapid economic development has changed rural life. Young adults today have joined the migrant work force in the cities; they meet, get married and settle down. Few rely on resources from home to find love.

Between 2011 and 2015, 20 million people a year settled in cities. By 2015, permanent urban residents accounted for 56 percent of the population.

Even the few left in villages are becoming tech savvy.

Thanks to the internet, they can now meet people on social media, rendering matchmakers obsolete.

Online dating has also boomed as investors cash in on a huge market. Jiayuan, one such website, said it has 160 million registered users.

While dating sites cater to the needs of urban lonely hearts, whose time is largely occupied by work, young adults in rural areas have more time and freedom to mingle.

"In the past, the bride and groom could not even meet without matchmakers. Now, few come to us for such an encounter," Zhang said.

If she accepted a job, families paid her with gifts of candy, tea and liquor, or sometimes cash amounting to 200 yuan ($30). "It was not enough to make a living, but I enjoyed doing it as a bit of philanthropy," Zhang said. "It was always a blessing to see couples live happily ever after."

Guo Xiurong, 75, and his wife were Zhang's first success story. Guo spoke highly of the old-fashioned matchmaker's role in making rural marriages possible.

On a sad note, another client, Chen Xiuqi, said even the best in the trade will eventually fade into history. Zhang sees a bright side though, adding, "As the profession disappears, it means our society has developed."