Accouterments of beauty that tell a dynasty's tale

|

A painting and calligraphic work by Emperor Huizong. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

Sumptuous details

The gold and silver jewelry from Southern Song is characterized by simple overall designs and sumptuous details, Shi says. "While artisans from the preceding Tang Dynasty favored streamlined, minimalist designs, their Song counterparts, thanks to the advances in metal crafts, were able to draw much more vivid, delicate and sometimes three-dimensional pictures within the tiny space available."

A shift in geopolitics was also reflected in that tiny space. During Tang, a powerful and open-minded China was engaged in trade and other types of exchanges with the rest of the world, Persia for example. Consequently, jewelry from the era sometimes bore marked foreign influences, as in the Western-style designs and the use of precious stones.

Song, especially Southern Song, was known for anything but military prowess. Although maritime trade was possible - in fact, it was at its height at the time - a shrunken empire was still cut off on land from a large part of the world.

Foreign influences waned, especially in aesthetics, matters that the successive Song emperors, many of whom were great artists themselves, took very seriously. "Song represented a time when immense cultural pride and military in-confidence work together to produce a more inward-looking attitude regarding art," Shi says. "As a result, the jewelry-making was more Chinese than it had been."

Weddings

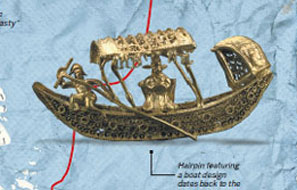

The biggest occasion for the commission of gold and silver jewelry was weddings. The "three gold" - a must for a proper wedding - included a gold bracelet, gold ring and gold scarf-weight (hanging on the edge of a scarf to keep it in place) for the bride.

However, Zhao Liya, whose research on ancient Chinese gold and silver jewelry is considered definitive and who acted as a consultant for the exhibition at the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, says the jewelry was rarely meant to last.

"Gold, valuable as it is, was consistently considered less precious than jade in ancient China. This had a lot to do with the meaning that people had read into these two different things. While jade symbolized purity, humility and righteousness, gold mainly stood for wealth."

In other words, while a jade hairpin was meant for posterity, it was not unusual for a gold one to be melted and remolded into something new and presumably more trendy.

"There was very little gold and silver jewelry of the type that we can see today that has been passed down from millennium, or half of a millennium, ago," Zhao says. "What is on view at the exhibition is mainly from underground storage, buried there when their owners fled the prolonged wars between Song and another rising - and much more brutal - power, the Mongols.

The war went on and off for nearly 45 years between 1235 and 1279. In 1279, eight years after the Mongol rulers founded the Yuan Dynasty (The capital was in Beijing), the last Song emperor - an 8-year-old boy - jumped into sea on the back of a loyal official. A page of history was turned.

The Mongol conquerors, described by some as "throat slayers", were not unknown for their killing sprees. Yet they spared all the craftspeople - goldsmiths and silversmiths included - so these artisans could continue to serve their new lords.

"Despite the rupture in many aspects of life - the Mongols were considered ethnic minorities with their own distinct culture - the metal jewelry from Yuan was not drastically different from that of Song," Shi says.

Over the past 60 years, especially since the 1970s, more and more discoveries have been made concerning those left-behind storage places. "Unlike tombs, these storage areas were not meant to be found. Almost all were discovered by local farmers by accident," Shi says.

Ripples

According to Zhao, culturally and artistically, Song has been sending ripples far into history, in fact much further than its successor may have wished to see.

"The flowers and butterflies in the Song paintings started to blossom and flutter on the metal jewelry designs of Yuan," she says. "The beauty of Song was gradually picked up, bit by bit, long after the demise of the empire."

And it was not just the jewelry. The Mongol rulers made Beijing their capital. And except for a relatively brief 50 years, Beijing was also the capital for the successive Ming and Qing dynasties. Yet Jiangnan, including Hangzhou and the surrounding area, continued to be the country's cultural hotbed

In 1488, a little more than 200 years after the fall of Song, a Korean boarding a ship landed on China's eastern coast by accident and traveled through what was once Southern Song's heartland. His memoir is now the basis for another exhibition at the Zhejiang Museum.

One thing that Shi wishes to emphasize is that although Song has gone down in history as a fragile beauty, in reality the economy boomed and people enjoyed affluent lives at the time.

"Before Song, mining was state controlled," Shi says. "The Song emperors opened the mining and smelting sector, including that of gold and silver, to private interests. Such policy had undoubtedly stimulated the making and use of jewelry."

Today these delicate hairpins and earrings from Song lie in the museum, with a patina that echoes their faint glimmer and tales that tell of a bygone era.