Shipbuilder sees a model future

|

|

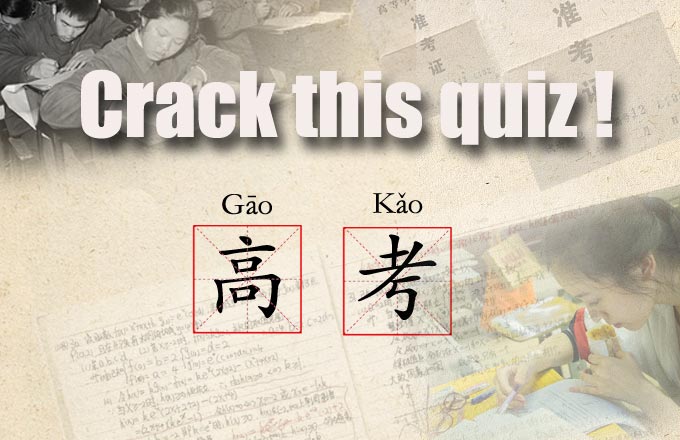

Shipbuilders apply traditional skills to craft a wooden boat in Zhangwan, Fujian province. [Photo/Xinhua] |

FUZHOU - On a simple workbench, a 1-meter-long model boat is nearing completion. The waxed redwood body shines in the sun and the hoisted sails look as if the ship is about to set off.

Liu Xixiu is modest about his work, and admits it's not perfect - pointing out some tiny parts he made by hand that don't suit him.

"I will take this ship to a fair in Taiwan and to a model contest in Shanghai. It has to be perfect," says Liu.

Liu is from Zhangwan township in Ningde, Fujian province. It is home to craftsmen who make ancient Chinese junks with battened sails called fuchuan, meaning Fujian vessels.

In 2010, the process of making watertight hulls used for fuchuan vessels was inscribed in UNESCO's List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Safeguarding.

Saturday is Chinese Cultural Heritage Day.

Liu's ancestors moved to the township around 600 years ago from southern Fujian, and the family has built ships ever since. Liu is the 20th generation of shipbuilders. His 30-square-meter studio - located on the roof of his two-story house - is about the size of half a badminton court and packed with planks of wood, saws, drills and hand planes.

It's just 100 meters from Zhangwan's shipbuilding plant.

"I often played there when I was young. My father used to be head of the plant," he says, looking out his studio window.

He liked woodworking when he was younger, which he attributes to his home environment. After graduating from high school in 1976, he worked at his father's factory as an apprentice.

"We didn't have textbooks. All the skills were just passed down," Liu recalls.

Being a quick learner, he became master in just three years, much quicker than his peers. He later taught himself ship design.

Fuchuan were used along the maritime Silk Road linking China, Southeast Asia and Western countries.

With modern shipbuilding and the rise of steel vessels, the wooden fuchuan gradually dwindled.

"We built over 200 vessels every year in the 1970s and '80s, drawing customers across China's coastal provinces, but now few orders come," he says, adding that none of his three children are interested in continuing the family tradition.

Following the inclusion of the watertight process in the national intangible cultural heritage list in 2008, followed by UNESCO's protection efforts in 2010, Liu sees some hope.

At the plant, a 44-by-12-meter vessel has been completed. The ship will be delivered to a local cultural company to be used for display and tourism. A research association on fuchuan has also been established.

"There are not many orders for big ships, but there are more for small ones - ship models," he says, adding that some companies have offered to hire him as a model designer.

Liu says fuchuan sounds like "fortune" in Chinese, and sails symbolize "a smooth path to success", drawing numerous clients - entrepreneurs and companies - longing for commercial success.

Near his studio is a seaport, where the maiden voyages of many ships have begun.

"I don't remember how many new vessels have sailed from there, but I'm sure there will be more," he says, gazing at the port through the window.