Friends and allies in war and peace

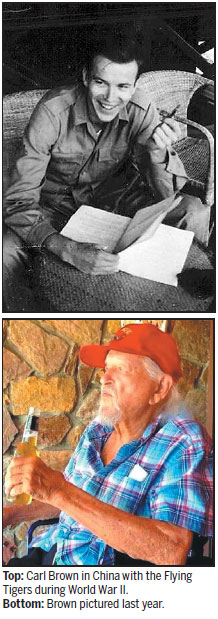

The last Flying Tigers

More than seven decades have passed since nearly 300 Flying Tigers arrived in China and wrote a legendary chapter in China-US relations.

Now, most of them have already died - not in battle - but of old age.

Only two survivors are left; Frank Losonsky, squadron crew chief, and the last surviving Flying Tiger pilot, Carl Brown. Armorer Charles Baisden died in February.

Losonsky was both a pilot and mechanical specialist when he arrived in Asia in 1941 at age 21. He was the youngest crew chief with the Flying Tigers, responsible for maintaining the shark-nosed P-40 fighters.

"I love Chinese people. They have pure hearts," Losonsky said, when he spoke with Xinhua. "It was dangerous in China, but I was happy to be there."

After returning to the US, he worked for General Motors and later ran three restaurants and a catering service. He also worked with his son, Terry, to publish his wartime diary.

Only once after WWII did Losonsky climb back inside a P-40. During a Flying Tigers reunion in Atlanta last year, he accepted a flight in a P-40, which performed two barrel rolls.

"I felt OK. No problem at all," he said afterward.

He always wanted to tread Chinese soil once again. His wish came true in 2015, when he was invited to visit for the Victory Day parade in Beijing, and was also made an honorary citizen of Kunming.

"China has changed so fast and so much," he said, adding that the places he lived in the 1940s were now unrecognizable.

"I am extremely excited about the progress China has made. I am sorry for the atrocities caused by the Japanese back then. The Chinese people were resolute in defeating them."

Brown attended Michigan State University until 1939, when he suspended his studies to join the US Navy. During his training in Florida, he became one of only a few pilots who could land a plane on an aircraft carrier at night.

In 1941, after being introduced to the AVG by friend Tex Hill, who became one of the AVG's ace pilots, Brown signed up for the unit and won an honorable discharge from the navy.

"Most of those pilots were just two to three years out of high school," Brown recalled.

"In Burma in 1941, the alert status was especially high. There was one rather heart-pounding experience; we had never employed a P-40 at night."

One night when Brown's squadron was guarding the Burma Road, the noise of trucks echoed around, sounding like a squadron of bombers with unsynchronized engines.

"So we had our big bomb alert and everybody took off because of the truck noises," Brown said of the false alarm.

He recalled a real alarm that happened during a mission in May 1942 when a plane being flown by an AVG pilot plane exploded by his wing: "I was thankful to have gotten back after that tragic encounter."

After the AVG disbanded, Brown spent three months training Chinese pilots, before becoming a pilot for CNAC. In total, he clocked up more than 1,000 hours over the Hump. He also flew airships across the Atlantic from New Jersey to West Africa and then India at least three times.

In 1945, he returned to the US, resumed his undergraduate studies and graduated in 1946. He went on to receive his medical degree in the 1950s and gained a doctorate in law in the 1980s.

For Brown, the horrors of WWII illustrate how desperately the world needs nonviolent solutions to interpersonal conflicts, and he pursued his degrees in this spirit of peaceful resolution, he said.

Brown will celebrate his 100th birthday in December.