Rural children more vulnerable to delayed brain development

|

|

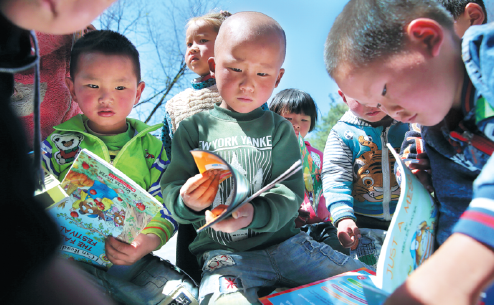

Youngsters in the southwestern province of Guizhou read books donated by volunteers. WANG JING/CHINA DAILY |

Since market reforms were initiated in 1978, China has moved from a centrally planned economy to one based on market forces.

Data from the National Bureau of Statistics show that in the past 12 years GDP growth has averaged about 10 percent a year, and more than 800 million people have been lifted out of poverty.

Despite those achievements, millions still live in poverty in the rural interior, where sturdy mules replace luxury cars and residents live in humble villages rather than tower blocks.

About 60 percent of young people in China are growing up in impoverished rural areas, and recent research suggests that, compared with their urban counterparts, they are more likely to fall at the starting line when it comes to education and future opportunities.

In June, a team from Stanford University's Rural Education Action Program published the results of a three-year research program that focused on the mental development of infants in rural areas.

In 2013, the first year, the team tested nearly 2,000 children ages 12 months to 6 in 351 villages in Shaanxi province. They used the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, which measure mental and physical development and assist in the diagnosis and treatment of developmental delays or disabilities, including cognitive, motor and behavioral.

Further surveys were conducted in the following two years. The results indicated that 41 percent of the children would experience delayed cognitive or motor development if they did not have effective interaction with caregivers when they were 18 to 24 months old. The figure rose to 53 percent for infants ages 24 to 30 months.

In 2015, in association with the National Health and Family Planning Commission, the program launched the same surveys among children ages 6 to 18 months in rural areas of Hebei and Yunnan provinces. In Hebei, 43 percent of babies showed signs of significant delay in either cognitive or motor development, or both. The rate in Yunnan was higher, with 60 percent experiencing the same problems.

When the surveys were conducted in urban areas the proportion was just 15 percent.

"There are about 50 million infants in China, and most of them live in rural areas. The delay in cognitive development will weaken their competitiveness in the labor market in the future, which may influence the quality of the country's overall labor force," said Zhang Linxiu, a researcher with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who led the study.

According to Liu Wenli, a researcher with the School of Brain and Cognitive Science at Beijing Normal University, interventions for children often focus on health, nutrition and stimulation during the first 1,000 days of life, because these factors result in an improved environment for brain development.

Optimal Intervention

However, the window for optimal intervention is short, according to Liu. "The number of new synapses (the junctions of nerve cells that allow electrical impulses to pass between them) peaks by about age 6 before decreasing over the next 6 years. This makes a compelling case for equitable investment in the development of cognitive capital during the early years," she said.

Scientific studies indicate that neuronal development is at its peak during the early years because 700 to 1,000 new neural connections are formed every second. The rate falls over time, and as much as 90 percent of a developing brain's final weight is established between ages 3 and 6.