Organ donation program moves into overdrive

In May, the Chinese medical professionals spent a week studying at the University of Barcelona in Spain.

The training will enable them to teach the postgraduate students at the universities in the next two years.

According to Marti Manyalich, president of the Donation and Transplantation Institute in Barcelona, the training is not just about sharing knowledge, but also about adapting the course to Chinese needs.

"Seven universities are not enough. We must train more Chinese professionals in more colleges in the coming decades," he said.

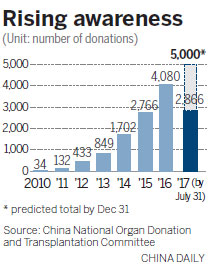

Spain has the highest organ donation rate in the world. Last year, the figure stood at 43.4 donations per 1 million people, while in China the number was just 2.98.

However, in 2010, the number in China was 0.03 people per 1 million.

One reason for Spain's success is that it pioneered the professionalization of donation programs. Starting in the 1980s, the University of Barcelona began offering graduate courses in organ donation, which were recognized and followed by other European countries.

Since then, Spain has taken the lead in establishing international training and exchanges, providing tuition to more than 10,000 professionals around the world.

China joined the project in 2013. Wang Lu, a colleague of Liu's who is also an organ donation coordinator, is one of the "seed doctors". She was impressed by the extensive, open discussions, scenario teaching and the Socratic tuition method, all of which are rare in Chinese training programs.

Liu said he learned that sometimes keeping silent during approaches to family members can be more effective than talking.

Meanwhile, Zhang Lize, a neurologist who took part in the training, said that humility wins trust: "This also applies to other aspects of the work."

Best prescription

However, despite the recent successes, some doctors still question the benefits of organ transplants, and are unwilling to help find potential donors among their patients. Some lack knowledge, while others prefer to avoid potential tensions with patients.

In some hospitals, organ procurement organizations - the teams responsible for evaluation and procurement - are poorly organized or severely marginalized, and there are no offices or full-time coordinators.

Chen Xiaosong, a coordinator at the Renji Hospital in Shanghai, is worried about finding doctors who want to teach the course and students interested in studying the subject, and no textbooks have yet been translated into Chinese.

Hou Fengzhong, deputy director of the China Organ Donation Administrative Center, said that although many remarkable achievements have been made in the past 10 years, China's organ donation program is still at a rudimentary stage, and society needs to work together as a whole to ensure faster progress in the future.

He advocated closer cooperation in the legal, economic, political and medical sectors.

He also suggested that the Ministry of Education should offer supportive policies to encourage more colleges, and even middle or primary schools, to host classes about organ donation.

Li Wenlei, a liver transplant specialist and head of the organ donation course at Capital Medical University in Beijing, said education is "the best prescription" for the national program.

"If organ donation is a river, then medical staff work downstream, dealing with individual cases," Li said.

"But when organ donation becomes a part of the education system, they will be able to move upstream and influence an entire generation."