Letter from Turpan: The grapes of wealth

In 1988, a farmer in Turpan stumbled upon an ancient tomb while cleaning out the sludge in a tunnel. Among the discoveries, archaeologists found, was a grape vine. It was later determined to be 3,000 years old, which puts the history of grape growing in Turpan back 1,000 years more than previously believed.

"The earliest places known to have grown grapes are around the Mediterranean and West Asia. Seeds were probably brought here along the Silk Road," explained Shi Huiqiong, a local official.

If you ask any Chinese to name one word associated with Turpan, it will no doubt be "grape", immortalized in classic songs and folk tales.

The place is located on the lowest altitude in the country, 150-plus meters below sea level and its the warmest in summer. But little do outsiders realize that the two are related. High temperature disparity between day and night and other favorable conditions produce the sweetest kinds of grapes.

"There are some 500 varieties here, but fewer than 100 are truly popular," said Shi. If you hear exotic and even erotic names such as "Fragrance of Women" and a body part of a horse I would not translate in this paper, it is not a title for porno movies.

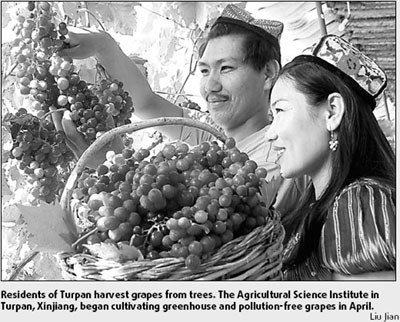

In a place where every farmer has a vineyard, it's only in recent decades that grapes are featured so prominently in the economy. In the early 1950s, there were only 20,000 mu (1,333 hectares) in the area. The acreage had grown 150 percent when the country carried out the reform and opening-up policy in the late 1970s. And now there are almost half a million mus, about one for each person. The fruit accounts for 60 percent of farmers' income.

If there is one person who should take the credit, it should be Haliqihan Yusup, a Uygur scientist who has spent decades teaching farmers to cultivate better grapes. "You should trim this darkened branch, and let that one have more sunshine. It'll bear fruit next season," this is a typical advice she offers.

Haliqihan graduated from an agriculture college in Xinjiang and started experimenting with 81 new breeds in the mid-1970s, some imported from other countries and others cultivated by a Beijing botanical institute. Every variety is like a child, loveable and naughty in its own way, she said.

When the economy got in the fast lane for reform, she encountered an unexpected problem: the plot she was working on was contracted out to farmers and she had to ask around for a vineyard to test her new methodology. One after another turned her down: "We've grown grapes for generations. We give the vines our sweat, and they give back sugary, sparkling grapes. What God does not give, we do not ask. God will not starve us. What does a young lady like you know about cultivating grapes?"

But she persisted and her efforts paid off. She taught them the ideal width of a furrow, the best ways to prune and other things. In two decades, crops per acre tripled in volume. Nowadays, the trend is to grow less.

"When production reaches 3-4 tons per mu, the fruit tends to be bland in taste. To keep our product upscale, we'll have to limit to 1-2 tons," said Shi from the publicity department.

With a million tons in annual output, Turpan has also improved the mix of fresh grapes and raisins from 20-80 several years ago to the present 40-60 percentage, which raises revenues for farmers. "Our grapes have thin skins and bruise easily, making it difficult to haul long-distance," said Shi. But one look at any outbound flight at a local airport, you get the impression that it is a freight plane piled up with grapes and raisins, with passengers as appendages.

(China Daily 09/07/2007 page6)