More money can mean rich man's burden

For many American professionals, the Labor Day holiday probably wasn't as relaxing as they had hoped. They didn't go into the office, but they were still working. As much as they may truly have wanted to focus on time with their children, their spouses or their friends, they were unable to turn off their BlackBerrys, their laptops and their work-oriented brains.

Americans working on holidays is not a new phenomenon: We have long been an industrious folk. A hundred years ago the German sociologist Max Weber described what he called the Protestant ethic. This was a religious imperative to work hard, spend little and find a calling in order to achieve spiritual assurance that one is among the saved.

Weber claimed that this ethic could be found in its most highly evolved form in the United States, where it was embodied by aphorisms like Ben Franklin's "Industry gives comfort and plenty and respect". The Protestant ethic is so deeply engrained in our culture you don't need to be Protestant to embody it. You don't even need to be religious.

But what's different from Weber's era is that it is now the rich who are the most stressed out and the most likely to be working the most. Perhaps for the first time since we've kept track of such things, higher-income folks work more hours than lower-wage earners do.

Since 1980, the number of men in the bottom fifth of the income ladder who work long hours (over 49 hours per week) has dropped by half, according to a study by the economists Peter Kuhn and Fernando Lozano. But among the top fifth of earners, long weeks have increased by 80 percent.

This is a stunning moment in economic history: At one time we worked hard so that someday we (or our children) wouldn't have to. Today, the more we earn, the more we work, since the opportunity cost of not working is all the greater (and since the higher we go, the more relatively deprived we feel).

In other words, when we get a raise, instead of using that hard-won money to buy "the good life", we feel even more pressure to work since the shadow costs of not working are all the greater.

One result is that even with the same work hours and household duties, women with higher incomes report feeling more stressed than women with lower incomes, according to a recent study by the economists Daniel Hamermesh and Jungmin Lee. In other words, not only does more money not solve our problems at home, it may even make things worse.

It would be easy to simply lay the blame for this state of affairs on the laptops and mobile phones that litter the lives of upper-income professionals. But the truth is that technology both creates and reflects economic realities. Instead, less visible forces have given birth to this state of affairs.

One of these forces is America's income inequality, which has steadily increased since 1969. We typically think of this process as one in which the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. Surely, that should, if anything, make upper income earners able to relax.

But it turns out that the growing disparity is really between the middle and the top. If we divided the American population in half, we would find that those in the lower half have been pretty stable over the last few decades in terms of their incomes relative to one another. However, the top half has been stretching out like taffy. In fact, as we move up the ladder the rungs get spaced farther and farther apart.

The result of this high and rising inequality is what I call an "economic red shift". Like the shift in the light spectrum caused by the galaxies rushing away, those Americans who are in the top half of the income distribution experience a sensation that, while they may be pulling away from the bottom half, they are also being left further and further behind by those just above them.

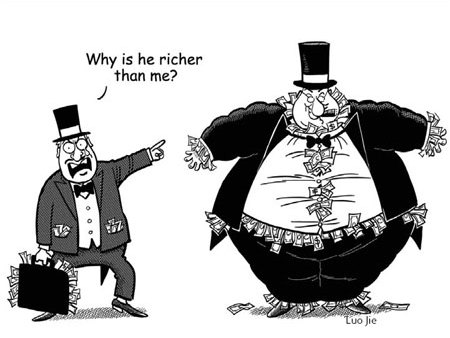

And since inequality rises exponentially the higher you climb the economic ladder, the better off you are in absolute terms, the more relatively deprived you may feel. In fact, a poll of New Yorkers found that those who earned more than $200,000 a year were the most likely of any income group to agree that "seeing other people with money" makes them feel poor.

Because these forces drive each other, they trap us in a vicious cycle: Rising inequality causes us to work more to keep up in an economy increasingly dominated by status goods. That further widens income differences.

The BlackBerrys and other wireless devices that make up our portable offices facilitate this socio-economic madness, but don't cause it. So, if you are someone who is pretty well off but couldn't stop working nonetheless, don't blame your iPhone or laptop. Blame a new wrinkle in something much more antiquated: inequality.

The author is the chairman of New York University's sociology department

The New York Times Syndicate

(China Daily 09/10/2008 page9)