50 years of democratic reform in Tibet

The Information Office of the State Council published a white paper titled Fifty Years of Democratic Reform in Tibet yesterday. Following is the full text:

Foreword

Tibet has been an inseparable part of China since ancient times. The peaceful liberation of Tibet, the driving out of the imperialist aggressor forces, the democratic reform and abolition of theocratic feudal serfdom in Tibet were significant parts of the Chinese people's national democratic revolution against imperialism and feudalism in modern history, as well as major historical tasks facing the Chinese government after the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

Prior to 1959, Tibet had long been a society of feudal serfdom under theocratic rule, a society which was even darker than medieval society in Europe. The 14th Dalai Lama, as a leader of the Gelug Sect of Tibetan Buddhism and also head of the Tibetan local government, monopolized both political and religious power, and was the chief representative of the feudal serf owners, who, accounting for less than 5 percent of the total population of Tibet, possessed the overwhelming part of the means of production, and monopolized the material and cultural resources of Tibet. The serfs and slaves, making up over 95 percent of the total population, suffered destitution, cruel oppression and exploitation, and possessed no means of production or personal freedom whatsoever, not to mention other basic human rights. The long centuries of theocratic rule and feudal serfdom stifled the vitality of Tibetan society, and brought about its decline and decay.

In 1951, the Agreement of the Central People's Government and the Local Government of Tibet on Measures for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet (hereinafter the "17-Article Agreement") was signed. The Agreement enabled Tibet to repel the imperialist forces and realize peaceful liberation, and provided basic conditions for Tibet to join the other parts of the country in the drive for common progress and development.

The "17-Article Agreement" acknowledged the necessity of reforming the social system of Tibet, and stressed that "the local government of Tibet should carry out reform voluntarily." However, in consideration of the special circumstances of Tibet, the Central People's Government adopted a circumspect attitude toward the reform. With great patience, tolerance and sincerity, it made efforts to persuade and waited for the local upper ruling strata of Tibet to carry out reform voluntarily. Instigated and supported by imperialist forces, however, some people in the upper ruling strata, despite the ever-growing demand of the people for democratic reform, were totally opposed to reform and proclaimed their determination never to carry it out. In an attempt to perpetuate feudal serfdom under theocracy, these people publicly abandoned the "17-Article Agreement" and brazenly staged an all-out armed rebellion on March 10, 1959. In order to safeguard the unity of the nation and the basic interests of the Tibetan people, the Central People's Government and the Tibetan people took decisive measures to quell the rebellion. Meanwhile, a vigorous democratic reform was carried out on a massive scale in Tibet to overthrow Tibet's feudal serfdom system under theocracy and liberate about 1 million serfs and slaves, ushering in a new era with the people becoming their own masters. The democratic reform was the most extensive, deepest and greatest social reform in the history of Tibet, and signified an epoch-making event in Tibet's history of social development and the progress of its human rights, as well as a significant advance in the history of human civilization and the world's human rights development.

Over the past half century, thanks to the care of the Central People's Government and aid from across the nation, the liberated people of all ethnic groups in Tibet have, in the capacity of masters of the nation, enthusiastically participated in the grand course of constructing a new society and creating their new lives, and worked miracles unprecedented in Tibetan history. The social system of Tibet has developed by leaps and bounds; its modernization has advanced rapidly; Tibetan society has undergone earth-shaking historic changes; and remarkable progress has been made in the cause of human rights, which has attracted worldwide attention.

The year 2009 marks the 50th anniversary of the democratic reform in Tibet. It is conducive to telling the right from wrong in history and helps the world better understand a real Tibet in progress for us to review the overwhelming democratic reform and the profound historical changes that have taken place in Tibet over the past 50 years, to shed light on the laws governing the social development of Tibet, and expose through facts the various lies and rumors spread by the 14th Dalai Lama and his hard-core supporters over the so-called "Tibet issue," as well as the true colors of the 14th Dalai Lama himself.

I. Old Tibet - A society of feudal serfdom under theocracy

Before the democratic reform in 1959, Tibet had been a society of feudal serfdom under theocracy, a society characterized by a combination of political and religious powers, and ruthless political oppression and economic exploitation of serfs and slaves by the serf-owner class, including three major estate-holders - local administrative officials, aristocrats and upper-ranking lamas in the monasteries. For centuries, the Tibetan people had been living in dire misery and suffering from the harshness of life, and their society had sunk into a grave state of poverty, backwardness, isolation and decline, verging on total collapse.

Medieval theocratic society. British military journalist Edmund Candler, who visited Lhasa in 1904, recorded the details of the old Tibetan society in his book The Unveiling of Lhasa: "... at present, the people are medieval, not only in their system of government and their religion, their inquisition, their witchcraft, their incarnations, their ordeals by fire and boiling oil, but in every aspect of their daily life." (The Unveiling of Lhasa, Edmund Candler. London: Pentagon, 2007) The most distinctive feature of the social system of old Tibet was theocracy, a system which ensured that the upper religious strata and the monasteries were together the political power holders as well as the biggest serf owners, possessing all kinds of political and economic privileges, and manipulating the material and cultural lives of the Tibetan people at their own advantage. Candler wrote in the book: "The country is governed on the feudal system. The monks are the overlords, the peasantry their serfs." "Powerful lamas controlled everything in Tibet, where even the Buddha himself couldn't do anything without the support of the lamas," he added. (The Unveiling of Lhasa, Edmund Candler. London: Pentagon, 2007) Statistics show that before the democratic reform in 1959, Tibet had 2,676 monasteries and 114,925 monks, including 500 senior and junior Living Buddhas and other upper-ranking lamas, and over 4,000 lamas holding substantial economic resources. About one quarter of Tibetan men were monks. The three major monasteries - Drepung, Sera and Ganden - housed a total of more than 16,000 monks, and possessed 321 manors, 147,000 mu (15 mu equal 1 hectare, it is locally called ke in Tibet - ed.) of land, 450 pastures, 110,000 head of livestock, and over 60,000 serfs. The vicious expansion of religious power under theocracy depleted massive human resources and most material resources, shackled people's thinking and impeded the development of productivity. Charles Bell, who lived in Lhasa as a British trade representative in the 1920s, described in his book Portrait of A Dalai Lama: The Life and Times of the Great Thirteenth that the theocratic position of the Dalai Lama enabled him to administer rewards and punishments as he wished, because he held absolute power over both this life and the next of the serfs, and coerced them with such power. (Portrait of A Dalai Lama: The Life and Times of the Great Thirteenth, Charles Bell, London: Collins, 1946) American Tibetologist Melvyn C. Goldstein incisively pointed out that Tibetan society and government were built upon a value system dominated by religious goals and behavior. Religious power and privileges, and the leading monasteries "played a major role in thwarting progress" in Tibet. Religion and the monasteries "were heavy fetters upon Tibet's social progress". "This commitment... to the universality of religion as the core metaphor of Tibetan national identity will be seen... to be a major factor underlying Tibet's inability to adapt to changing circumstances." (A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State, Melvyn C. Goldstein. California: University of California, 1991)

Means of production mostly monopolized by the three major estate-holders. The three major estate-holders, that is, local administrative officials, aristocrats and upper-ranking lamas in the monasteries, and their agents, accounted for less than five percent of Tibet's population, but owned all of Tibet's farmland, pastures, forests, mountains, rivers and beaches, as well as most livestock. About 90 percent of old Tibet's population was made up of serfs, called "tralpa" in Tibetan (namely, people who tilled plots of land assigned to them and had to provide corvee labor for the serf owners) and "duiqoin" (small households with chimneys emitting smoke). They had no means of production or per-sonal freedom, and the survival of each of them depended on tilling plots for the estate-holders. In addition, "nangzan," who comprised five percent of the population, were hereditary slaves, known as "speaking tools." Statistics released in the early years of the Qing Dynasty in the 17th century indicate that Tibet then had more than three million mu of farmland, of which 30.9 percent was owned by the local feudal government, 29.6 percent by aristocrats, and 39.5 percent by monasteries and upper-ranking lamas. The three major estate-holders' monopoly of the means of production remained unchanged until the democratic reform in 1959. Before 1959, the family of the 14th Dalai Lama possessed 27 manors, 30 pastures and over 6,000 serfs, and annually squeezed about 33,000 ke (one ke equals 14 kilograms - ed.) of qingke (highland barley), 2,500 ke of butter, two million liang (15 liang of silver equal one silver dollar of the time) of Tibetan silver, 300 head of cattle, and 175 rolls of pulu (woolen fabric made in Tibet) out of its serfs. In 1959, the Dalai Lama alone owned 160,000 liang of gold, 95 million liang of silver, over 20,000 pieces of jewelry and jadeware, and more than 10,000 pieces of silk and satin fabric and rare fur clothing, including over 100 robes inlaid with pearls and gems, each worth tens of thousands of yuan.

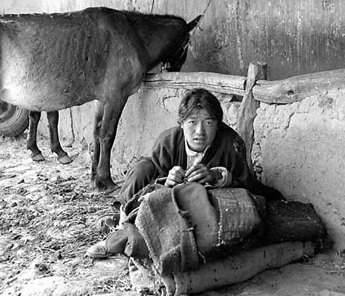

|

This file photo shows a serf living in a stable before the democratic reform in 1959. Xinhua |

Serfs owned by the three major estate-holders. The local government of old Tibet prescribed that serfs must stay on the land within the manors of their owners, and were not allowed to leave without permission, and were strictly prohibited from fleeing the manors. They were serfs from generation to generation, confined to the land of their owners. All serfs and their livestock with labor ability had to till the plots of land assigned to them and provide corvee labor. Once the serfs lost their ability to labor, they were deprived of livestock, farm tools and land, and degraded to the status of slaves. The serf-owners literally possessed their serfs as private property, they could trade and transfer them, present them as gifts, make them gambling stakes or mortgages for debt and exchange them. According to historical records, in 1943 the ariscrat Trimon Norbu Wan-gyal sold 100 serfs to a monk official at Kadron Gangsa, in the Drigung area, each serf for 60 liang of silver. He also sent 400 serfs to the Kunde Ling Monastery as a payment for a debt of 3,000 pin of silver (one pin equals 50 liang of silver). The serf-owners had a firm grip on the birth, death and marriage of serfs. A Tibetan ballad of the time goes, "Our lives were given to us by our parents, but our bodies are owned by our lords. We are not masters of our own lives or bodies, or of our own destiny." All serfs had to ask their owners for permission to marry, and male and female serfs not belonging to the same owner had to pay "redemption fees" before they could marry. After marriage, serfs were also taxed for their newborn children. Children of serfs were registered the moment they were born, sealing their life-long fate as serfs.

Rigid hierarchy. The "13-Article Code" and "16-Article Code, " which were enforced for several hundred years in old Tibet, divided people into three classes and nine ranks, enshrining inequality between the different ranks in law. The Code stipulated that people were divided into three classes according to their family background and social positions, each class was further divided into three ranks. The upper class consisted of a small number of aristocrats from big families, high-rank Living Buddhas and senior officials; the middle class was composed of lower-ranking ecclesiastical and secular officials, military officers, and the agents of the three major kinds of estate-holders. Serfs and slaves constituted the lower class, accounting for 95 percent of Tibet's total population. The provision concerning the penalty for murder in the Code provided, "As people are divided into different classes and ranks, the value of a life also differs." The bodies of people of the highest rank of the upper class, such as a prince or Living Buddha, were literally worth their weight in gold. The lives of people of the lowest rank of the lower class, such as women, butchers, hunters and craftsmen, were only worth a straw rope. The "Report on the Prohibition against Taking in Descendents of Blacksmiths" kept in the Archives of the Tibet Autonomous Region showed that in 1953, when the 14th Dalai Lama found out that one of his servants was a blacksmith's descendent, he immediately expelled the servant, and announced that descendents of gold, silver and iron smiths, and butchers belonged to the lowest rank of the lower class, and were forbidden to serve in the government or marry people from other ranks or classes. Tibetologist Tom Grunfeld of the State University of New York, USA, noted in his book The Making of Modern Tibet that equality among mankind, though incorporated in the doctrines of Buddhism, unfortunately failed to prevent the Tibetan rulers from setting up their own rigid hierarchical system.

Cruel political oppression and corporal punishments. As stipulated in the Tibet's local code, when serfs "infringe upon" the interests of the three estate-holders, the estate-holders can "have their eyes gouged out, legs hamstrung, tongues cut out, or hands severed, or have them hurled from a cliff, drowned or otherwise killed; such punishments are warning to others not to follow their example." Any serf "who voices grievances at the palace, behaving disgracefully, should be arrested and whipped; anyone who disobeys a master shall be arrested; anyone who spies on a master shall be arrested; a commoner who offends an official shall be arrested." When people of different classes and ranks violated the same criminal law, the criteria for imposing penalties and the means of punishment were quite different in old Tibet. As stipulated in the Code, a servant who fought and severely injured his master could have his hands or feet chopped off; but a master who injured a servant only need to give the servant medical treatment; and a servant who injured a Living Buddha was deemed to have committed a felony and would have his eyes gouged out, a limb amputated, or even put to death.

A Russian traveler in Lhasa in the early 20th century, wrote in his book A Buddhist Pilgrim to the Holy Place of Tibet: "The offenders are mostly poverty-stricken Tibetans punished either by having their fingers or noses cut off, or, in most cases, by being blinded in both eyes. Such disfigured and blind people are seen begging in the streets of Lhasa every day. Exile is another type of punishment. Offenders are shackled and chained, and have to wear a large round wooden collar around their necks all their life. They are sent to remote regions for hard labor or work as serfs for feudal aristocrats and patriarchal chiefs. The most severe punishment of all is, of course, the death penalty, with the victims drowned in rivers (as in Lhasa) or thrown over rocky cliffs (as in Xigaze)." (A Buddhist Pilgrim to the Holy Place of Tibet, Gombojab Tsebekovitch Tsybikoff)

David MacDonald, a Briton, wrote in his book "The Land of the Lama": "Capital punishment is deemed the heaviest category of punishment in Tibet, to which the most inhuman practice of dismemberment is added based on the hypothesis proposed by Tibetan lamas that after dismemberment the human soul cannot be reincarnated. The most common practice is to throw the condemned prisoner into a river in a leather wrapper, which will sink in about five minutes. If he remains alive after this time, he will be tossed into the water again until he dies. Afterwards, the body will be dismembered, and hurled into the river to drift downward with the current... Even more appalling is the practice of gouging out a prisoner's eyes. A piece of heated, U-shaped iron is inserted into the eye sockets, or boiling water or oil is poured in, and the eyeballs are prized out with an iron hook." (The Land of the Lama, David MacDonald)

There were penitentiaries or private jails in monasteries and aristocrats' residences, where instruments of torture were kept and clandestine tribunals held to punish serfs and slaves. In the Ganden Monastery there were many handcuffs, fetters, cudgels, and instruments of torture used for eye gouging and hamstringing. The private monastery administrative office set up by Trijang Rinpoche, junior tutor of the present 14th Dalai Lama, killed and injured more than 500 serfs and poor monks, in Dechen Dzong (present-day Dagze County) jailed 121 people, sent 89 into exile, forced 538 into slavery, forced 1,025 commoners into exile, forced 72 divorces, and 484 women were raped there.

In the Archives of the Tibet Autonomous Region there is a letter from a department of the Tibet local government to Rabden in the early 1950s, saying that, to celebrate the Dalai Lama's birthday, all the staff of Gyumey would chant the sutra. To successfully complete this ceremony, some special food would be thrown to the animals. Thus, a corpus of wet intestine, two skulls, many kinds of blood and a full human skin were urgently needed, all of which must be promptly delivered. A religious ceremony for the Dalai Lama used human blood, skulls and skin, showing how cruel and bloody the feudal serfdom system under theocracy was in old Tibet.

Heavy taxes and larvee. Serf owners exploited serfs by imposing corvee labor, taxes and levies, and rents for land and livestock. There were over 200 kinds of taxes levied by the former local government of Tibet alone. Serfs had to contribute more than 50 percent or even 70 to 80 percent of their labor, unpaid, to the government and manor owners. At feudal manors, serf owners divided the land into two parts: Most fertile land was kept as manor demesne while infertile and remote lots were rented to serfs on stringent conditions. To use the lots, serfs had to work on the demesne with their own farm implements and provide their own food. Only after they had finished work on the demesne could they work on the lots assigned to them. In the busy farming season or when serf owners needed laborers, serfs had to contribute man and animal power gratis. In addition, serfs had to do unpaid work for the local government of Tibet and its subordinate organizations, among which the heaviest was transport corvee, because Tibet is large but sparsely populated and all kinds of things had to be transported by man or animal power.

According to a survey conducted prior to the democratic reform of Tibet, the Darongqang Manor owned by Gyaltsap Tajtra had a total of 1,445 mu of land, and 81 able-bodied and semi-able-bodied serfs. They were assigned a total of 21,266 corvee days per year, the equivalent of an entire year's labor by 67.3 people, 83 percent of the total. The Khe-sum Manor, located by the Yarlung River in present-day Nedong County, was one of the manors owned by aristocrat Surkhang Wang-chen Gelek. Before the democratic reform, the manor had 59 serf households totaling 302 persons and 1,200 mu of land. Every year, Surkhang and his agents levied 18 taxes and assigned 14 kinds of corvee, making up 26,800 working days; the local government of Tibet levied nine kinds of taxes and assigned 10 kinds of corvee, making up more than 2,700 working days; and Riwo Choling Monastery levied seven kinds of taxes and assigned three kinds of corvee, making up more than 900 working days; on average, every laborer had to do over 210 days of unpaid work for the three estate-holders, and contribute over 800 kilograms of grain and 100 liang of silver.

Exploitation through usury. Each Dalai Lama had two money-lending agencies. Some money coming from "tribute" to the Dalai Lama was lent at an exorbitant rate of interest. According to re-cords in the account books of the two agencies, in 1950 they lent 3,038,581 liang of silver as principal, and collected 303,858 liang in interest. Governments at different levels in Tibet also had many such agencies, and lending money and collecting interest became one of the officials' duties. A survey done in 1959 showed that the three major monasteries, namely Drepung, Sera and Ganden, in Lhasa lent 22,725,822 kilograms of grain and collected 399,364 kilograms in interest, and lent 57,105,895 liang of silver and collected 1,402,380 liang in interest. Revenue from usury made up 25 to 30 percent of the total revenue of the three monasteries. Most aristocrats were also engaged in usury, with the interest accounting for 15 to 20 percent of their family revenues. Serfs had to borrow money to survive, and more than 90 percent of serf households were in debt. French traveler Alexandre David-Neel wrote in his book Le Vieux Tibet Face a la Chine Nouvelle (Old Tibet Faces New China), "All the farmers in Tibet are serfs saddled with lifelong debts, and it is almost impossible to find any of them who have paid off their debts." Serfs were burdened with new debts, debts passed down from previous generations, debts resulting from joint liability, and debts apportioned among all the serfs. The debts that were passed down from previous generations and could never be re-paid even by succeeding generations accounted for one third of the total debts. The grandfather of a serf named Tsering Gonpo in Maizho-kunggar County once borrowed 50 ke of grain from the Sera Monastery. In 77 years the three generations of the family had paid more than 3,000 ke of grain in interest, but the serf owner still claimed that Tsering Gonpo owed him 100,000 ke of grain. There was another serf named Tenzin in Dongkar County who borrowed one ke of qingke from his master in 1941. In 1951 he was ordered to pay back 600 ke. Tenzin could not pay off the debt, and had to flee. His wife committed suicide, and his seven-year-old son was taken away to repay the debt.

A stagnant society on the edge of collapse. Ruthless oppression and exploitation under the feudal serfdom of theocracy stifled the vitality of Tibetan society and reduced Tibet to a state of chronic stagnation for centuries. Even by the middle of the 20th century, Tibet was still in a state of extreme isolation and backwardness, almost without a trace of modern industry, commerce, science and technology, education, culture or health care. Primitive farming methods were still being used, and herdsmen had to travel from place to place to find pasture for their livestock.

There were few strains and breeds of grains and animals, some of which had even degenerated. Farm tools were primitive. The level of both the productive forces and social development was very low. Deaths from hunger and cold, poverty and disease were commonplace among the serfs, and the streets of Lhasa, Xigaze, Qamdo and Nagqu were crowded with male and female beggars of all ages. American Tibetologist A. Tom Grunfeld pointed out that, although some people claimed before 1959, ordinary Tibetan people could enjoy milk tea as they wished and a great deal of meat and vegetables, a survey conducted in eastern Tibet in 1940 showed that 38 percent of Tibetan families never had tea to drink, 51 percent could not afford butter, and 75 percent sometimes had to eat weeds boiled with ox bones and oat or bean flour. "There is no evidence to support the picture of Tibet as a Utopian Shangrila."

Plenty of evidence demonstrated that by the middle of the 20th century the feudal serfdom of theocracy was beset with numerous contradictions and plagued by crises. Serfs petitioned their masters for relief from their burdens, fled their lands, resisted paying rent and corvee labor, and even waged armed struggle. Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, once a Galoin (cabinet minister) of the former local government of Ti-bet, pointed out that "all believe that if Tibet goes on like this the serfs will all die in near future, and the aristocrats will not be able to live either. The whole Tibet will be destroyed." (The highest school of the Gelug Sect in Tibet. - ed.)

II. Momentous democratic reform in Tibet

Carrying out democratic reform and abolishing the feudal serfdom of theocracy was an inevitable requirement for social progress. It was a major task of the people's democratic revolution led by the Communist Party of China, and was the only solution for social development in Tibet. Moreover, it reflected the yearning of the overwhelming majority of the Tibetan people. In 1959, the Central People's Government carried out a great historical reform in Tibetan history, and profoundly changed the fate of the Tibetan people by launching the democratic reform and abolishing serfdom, a grim and backward feudal system.

The People's Republic of China was founded in 1949, when the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) won decisive victories over the Kuomintang troops. Beiping (now Beijing) and provinces like Hunan, Yunnan, Xinjiang and the former Xikang were all liberated peacefully from the rule of the former Kuomintang government. In light of the actual situation in Tibet, the Central People's Government also decided to use peaceful means to liberate Tibet. In January 1950, the Central People's Government formally notified the local authorities of Tibet to "send delegates to Beijing to negotiate the peaceful liberation of Tibet." In February 1951, the 14th Dalai Lama sent Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme as his chief plenipotentiary, and Kemai Soinam Wangdui, Tubdain Daindar, Tubdain Legmoin and Sampo Dainzin Toinzhub as delegates to Beijing to handle with full power the negotiations with the Central People's Government. On May 23, 1951, the "17-Article Agreement" was signed in Beijing and Tibet was thus liberated peacefully. The peaceful liberation enabled Tibet to shake off the trammels imposed by imperialist aggressors, brought to an end to the long-term isolation of Tibet and stagnancy of its social development, thus creating favorable conditions for democratic reform and social progress in Tibet.

The "17-Article Agreement" gained the approval and support of people of all ethnic groups in Tibet. In September 26-29th, 1951, the local Tibetan government held a meeting to discuss the Agreement, joined by all ecclesiastical and secular officials and representatives from the three prominent monasteries. The participants concurred that the Agreement "is of great and incomparable benefit to the grand cause of the Dalai Lama, Buddhism, politics, economy and other aspects of life in Tibet. Naturally, it should be carried out." The 14th Dalai Lama sent a telegram to Chairman Mao Zedong on October 24, 1951, stating that "On the basis of friendship, the delegates of the two sides signed on May 23, 1951 the Agreement on Measures for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet. The local Tibetan government as well as ecclesiastical and secular people unanimously support this Agreement, and, under the leadership of Chairman Mao and the Central People's Government, will actively assist the PLA troops entering Tibet in consolidating national defense, ousting imperialist forces from Tibet and safeguarding the unification of the territory and the sovereignty of the motherland." In 1954, the 14th Dalai Lama and the 10th Panchen Lama participated in the First National People's Congress (NPC) in Beijing, with the former elected vice-chairman of the NPC Standing Committee and the latter a member of the same committee. The 14th Dalai Lama addressed the meeting, fully endorsing the achievements made since the implementation of the "17-Article Agreement" three years earlier, and expressing his warm support for the principles and rules regarding the regional autonomy of ethnic minorities. On April 22, 1956, he became chairman of the Tibet Autonomous Region Preparatory Committee. In a speech at the founding of the committee, he reaffirmed that the Agreement "had enabled the Tibetan people to fully enjoy all rights of ethnic equality and to embark on a bright road of freedom and happiness."

(China Daily 03/03/2009 page8)