Will Asia use crisis as catalyst for change?

Will Asia - in particular China and India - be able to avoid a deep recession amid the current breakdown of the global financial system and the resultant collapse of international trade and investment?

Some observers paint a rosy picture of a region that will fare much better than during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Some even talk about signs of recovery. But the data contradict these expectations. In fact, Asia is suffering even more today than it did in 1997. The speed and ferocity of the region's economic downturn have shocked even the pessimists.

Asian Development Bank projections for 2009 show a 3.4 percent decline of gross domestic product in Asia (outside of Japan), down from 6.3 percent growth in 2008. By contrast, IMF data show that even during the peak of the 1997 financial crisis, Asia continued to grow by around 3.7 percent.

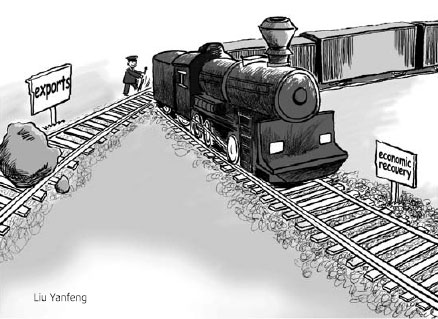

We need to discard the rosy picture and address explicitly the potentially game-changing impact of the crisis. An important characteristic of the current crisis is that the more export-oriented a country, the more vulnerable it is.

Korea - a leading exporter of memory chips, mobile handsets, cars and ships - has been hit hard by the global downturn. In February, Korean exports dropped as much as 26 percent from a year ago and imports plunged 40 percent, dragging down industrial production and investment and increasing unemployment.

And what about China, a country whose rise as the dominant global factory has catapulted it over the last few years into the exclusive club of global economic powers?

The World Bank projects a 6.5 percent growth this year. While this looks like a dream figure from a US perspective, from a Chinese perspective it actually represents quite a dramatic decline from the 9 percent growth in 2008. Most importantly, a 6.5 percent growth may be insufficient to cope with China's growing unemployment.

Of particular concern to the Chinese government is rising unemployment for migrant workers and university graduates. The government estimates that 20 million migrant workers lost their jobs or were unable to find employment in 2008, and the picture may grow worse in 2009. China's Academy of Social Sciences reports that 7.8 million graduates will search for jobs this year. Of these, up to 40 percent - around 3 million - will not find jobs. Pieter Bottelier, a respected China expert, projects that, overall, 48 million Chinese may be looking for jobs this year, while the number of newly created jobs is likely to be less than 7 million.

How deep and persistent will Asia's downturn be? If the world economy will take years and not months to recover, which I think it will, it follows that profound adjustments may well be necessary in Asia's export-oriented development model.

Take China for instance. Driven by a rapidly expanding global economy, its dependence on international trade has doubled since 1998, from 30 percent of the GDP to as high as 60 percent in 2008. But this year, both international trade and investment are falling off the cliff.

As the global crisis deepens and hits demand in the US and Europe as well as in emerging economies, Chinese exports have suffered the biggest slide in a decade - 26 percent in February - while its imports fell almost 24 percent.

Coping with these fundamental external disruptions will require profound adjustments. Hence the real question is, both for China and for Asia at large: Will governments be able to use the crisis as a broad catalyst for change? There is much talk that Asia needs to upgrade its economies through innovation. Such a shift in strategy is necessary to address the region's vast needs for food, shelter, medical services and infrastructure, and to counter its environmental degradation.

But as of now, Asia is still ill-prepared to mobilize resources for economic recovery. As a share of the GDP, the stimulus packages announced in much of Asia are considerably smaller than in the US (8 percent), Japan (6 percent) and Germany (3 percent) - with two exceptions: Singapore (3.2 percent) and China (7.1 percent). What sets China apart from its Asian neighbors is that high fiscal reserves and a very low level of debt provide ample resources to continue priming the economy.

Most observers expect China to move sooner than most other countries to economic recovery. This could facilitate attempts to implement real "upgrading through innovation" strategies. But a relatively quick recovery could also undermine such efforts as so many vested interests (in State-owned enterprises and the national security apparatus) are pushing for the status quo.

There are some positive changes already in the works - efforts to promote new domestic industries like next generation vehicles and creating a domestic solar market. China's stimulus package also includes substantial investments in healthcare and education, two key aspects of building up a more diversified economy, where manufacturing is complemented by a domestic service economy.

Yet even for China, the barriers remain stacked high against attempts to use the crisis as a catalyst for change. For instance, the freefall in global demand, combined with widespread excess capacity, is giving rise to price deflation and reduced wages, which in turn will constrain China's own consumption.

The scariest prospect is that the crisis may well prompt governments worldwide to move toward more protectionist policies, possibly igniting trade wars with global ramifications.

Let's hope that leaders in Asia as well as in the US, Japan and the EU recognize the urgent need for new strategies and new economic growth models before that disturbing scenario comes to pass.

The author is a Senior Fellow in Economics at the East-West Center in Honolulu Research Program.

(China Daily 04/24/2009 page9)