Tweeny bit spoilt

|

Parents and experts are increasingly worried that young Chinese, such as these teenagers at Xidan shopping area in Beijing, have become the family's biggest consumers. Jiang Dong |

Ma Qing sits on the sofa holding her knees, trying to hold back her tears. Her 11-year-old daughter Mengmeng has been weeping in her room for hours because Ma refused to buy a dress for her. The 36-year-old mother believes the strapped dress made by a famous label is too expensive and revealing. But it seems she has to compromise.

Before locking herself inside, Mengmeng protested: "Mom, you have no right to interfere with my choice." She has already "persuaded" her mom to allow her lipstick, nail polish, wedge heels and corset by going on "hunger strike".

Ma has been losing ground, ever since the girl started earning her own money.

Six years ago, Mengmeng earned 300 yuan ($43) as a flower girl at her aunt's wedding. When a wedding ceremony company asked her parents if she could appear at other weddings, Ma and her husband thought it would be a good way for Mengmeng to broaden her horizons and learn how to manage money.

For three years, the Guangzhou high school student spent her weekends and holidays as a flower girl and earned 4,000 yuan each year. She stopped attending weddings three years ago but still amassed a considerable sum. Moreover, Ma and the teachers find Mengmeng to be more mature and confident than her friends, though the flipside is she is no longer satisfied with simple gifts.

Actually, Mengmeng is not the only demanding child. Ma's friend, a university lecturer in Shanghai, recently bought an Audi A4 for 300,000 yuan ($43,900) but his son, who is about the same age as Mengmeng, still says it isn't good enough, since some of his classmates' parents are driving more expensive limos.

"What's happening with today's children? Why are they so different from us when we were young?" Ma sighs.

Numerous Chinese parents are faced with the same dilemma. On Children's Day the Southern Metropolis Weekly carried a series of reports that revealed some striking facts about Chinese children's consumption demands.

Almost overnight, Chinese parents have discovered their children are the family's biggest consumers. Some analysts say that a "tween" generation bent on materialistic pursuits has appeared in China.

In 2003, popular US author Martin Lindstrom discussed the consumption needs of "tweens" (children aged 9-14) around the world in BRANDchild: Inside the Minds of Today's Global Kids: Understanding Their Relationship with Brands.

Based on a survey of children in 11 countries, Lindstrom estimated that although the tweens still relied on their parents, they already had an independent sense of brand values. Tweens spent $1 trillion a year and influenced their parents' choices in purchasing at least 60 percent of brand products.

Tweens are heavily influenced by the media and absorb an average of 40,000 advertisements every year - almost 110 per day. An estimated $25 billion worth of ads was spent on advertising that targeted the youngsters.

When Lindstrom's book was published in China in 2004, "tweens" was translated into a more sensational term "tun shi dai" (Swallow Generation). But it has taken several years for them to raise eyebrows here.

In 2003, very few Chinese children met the requirements of "tweens" set by Lindstrom regarding pocket money, online access and media exposure. Six years later, things have changed dramatically.

When Premier Wen Jiabao said in his government work report in March that the per capita disposable income for the country's urban residents was 15,781 yuan last year, surveys show that the average annual spending by children in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and other major cities had exceeded 10,000 yuan a few years ago.

According to a nationwide survey conducted by Beijing-based Answer Marketing Consulting Ltd in 2007, nearly 40 percent of children aged 7-10 use the Internet, rising to nearly 60 percent for those aged 11-13.

The rating of the children's channel on China Central Television (CCTV) has soared from 0.1 percent in 2003 to 2.35 percent in 2008. Each day, an estimated 150 million children watch cartoons, advertisements and other programs.

Xu Qingliang, executive editor of Southern Metropolis Weekly, says there are complex reasons for Chinese children's increased spending.

Most Chinese families with tweens only have one child and a lot of those parents were also the only children when they grew up. So, as long as the child's demand is reasonable, parents normally allow them to buy what they want.

Children are curious of novel things and manufacturers have developed strategic advertisements for children of different ages.

Mo Zijin, who used to be a chief creative officer in an advertisement company, likens a successful ad aimed at children to "a shining golden chain", each ring of which is crafted with careful planning. When the ad is shown to the public, the chain "clicks tight and locks the children's hearts and their parents' purses".

Mo says parents of babies and toddlers take all the decisions when buying milk powder, clothes and toys but this changes as children enter kindergarten, pay more attention to TV and learn to choose based on their schoolmates' trends.

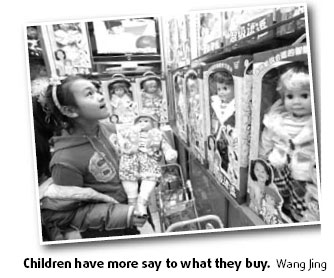

By about 10, children have formed their own individual needs and consumption habits, some even following certain brands. With their allowances growing, they have more say to what they buy. The parents' opinion often counts for less than the charming smile of an idol.

Mo says some advertisers even depict parents as "outdated foolish people who don't understand children's needs".

Recently, many parents have been nervous to see their children asking for an alcohol-free drink that tastes like beer, made by Wahaha, a famous Chinese drinks producer. If the parents disagree, the children mimic the ads and say their parents are "out".

Novel figures, dramatic storyline, bright colors, melodious music and catchy phrases can easily capture children's hearts, Mo says.

Dr Hu Xiaohong of the Guangdong University of Foreign Studies researched children's consumption. She believes that the family is the major influence on children aged 7 and 11. From 11 to 14, though, peer influence grows.

This January, Hu saw a group of young boys surrounding some handsome young men in their 20s who were demonstrating dazzling skills on a two-wheeled skate board in his neighborhood community.

Hu immediately bought a board for her young boy, even though she knew it was "buzz marketing" devised to win children's trust.

During the Spring Festival, a film on the fight between the Hui Tailang (Big Big Wolf) and Xi Yangyang (Pleasant Goat) became a blockbuster that netted 85 million yuan. Creative Power Entertaining, a company based in Guangzhou, has since developed 200 products based on the film.

Yang Xueping, spokesman for the company recently bought her daughter a pencil container painted with Mei Yangyang, a charming female goat in the film. She claims all the other girls in the class chased her daughter and wanted to buy the same container.

"Children like to have what their pals have," Yang says. "When they like a cartoon, they'll be interested in any product related to the cartoon."

Hu says children want such items so they can socialize with other children. "Consumption is a symbol that realizes the consumer's value," she says.

(China Daily 06/08/2009 page8)