More than just income gap to bridge

On Oct 1, 2009, Beijing celebrated the 60th anniversary of founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC). When Chairman Mao Zedong and his comrades established the new government they hoped to create an equitable and classless society.

To be fair, Chairman Mao did accomplish a lot. He united most of the country, stabilized the economy and expelled the imperialists. The charismatic leader also made education and healthcare accessible to people in much of the nation's countryside. The rampant corruption and exploitation of the poor that had characterized Chinese society in past centuries was reduced dramatically.

On the other hand, the period was also marked by a series of chaotic mass campaigns such as the "100 flowers blossom" (1956-57), the "great leap forward" (1958-1961) and the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976).

In the late 1970s, Deng Xiaoping launched a series of economic reforms. The pragmatic leader declared: "To get rich is glorious." But he cautioned that some people would get rich before others. Small "pockets of a free market" (special economic zones or SEZs) eventually gave way to what is now described officially as "socialism with Chinese characteristics". But like the earlier era, the record of the reform era is a mixed one.

The PRC now has the fastest growing economy in the world. Between 1979 and 2007, the average rate of GDP growth was roughly 10 percent. More than 300 million Chinese have been lifted out of poverty. In 2005, George W. Bush, then US president, declared: "China is a great nation that is growing like mad." More recently, US President Barack Obama said the PRC is "a majestic country".

According to some estimates the Chinese mainland will overtake America as the world's largest economy within 20 years. In short, the country is widely acclaimed as an economic miracle. China certainly has made impressive strides during the "reform era". But storm clouds have been gathering on its horizon.

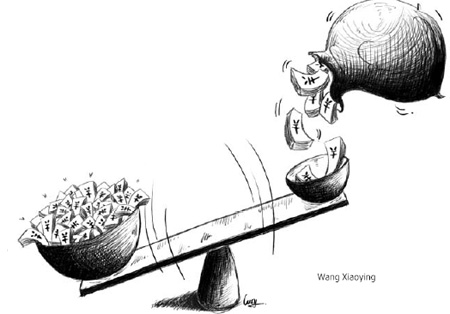

Inequalities are growing in China. The country's Gini coefficient, a measurement of income inequality, rose from 0.18 in 1978 to 0.36 in 1990. Since then, it has soared to roughly 0.50, the highest in East Asia. Income distribution on the mainland cannot be compared to South Korea or Taiwan. Rather, it now resembles some Latin American countries.

A survey conducted by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) shows that the average income of the mainland's urbanites is approximately 3.1 times that of its rural residents. Moreover, the inequalities that exist between the provinces are even more pronounced. For example, people living in Guizhou, a landlocked province, earn a fraction of what residents in coastal provinces like Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shandong or Guangdong do. In fact, the income of farmers in Guizhou is less than 10 percent of the average salary of a Shanghai resident.

These trends are growing. In fact, it appears that the old adage, "the rich are getting richer, while the poor are getting poorer" now applies to China. The CASS says the top 10 percent of the population with the highest incomes control 40 percent of all assets in the country, while the poorest 10 percent possess just 2 percent. And many of the rich enjoy flaunting their newfound wealth in front of the less fortunate. Growing inequalities in China are not limited to income. Educational opportunities are become increasingly uneven, and accessibility to healthcare is becoming especially pronounced. As The Lancet, the world's leading medical journal, reported, "Significant differences in health status exist between population groups in China." The life expectancy in Shanghai is 78 years, while in the poorest provinces it is only 65 years. These gaps in average life expectancy are significantly more than those found in many other countries.

The central leadership is aware of the problems associated with rapid economic development and it is taking aggressive steps to solve them. For example, the central government is trying to improve living conditions in the countryside through numerous infrastructure improvement programs (building roads and water purification plants, and improving electricity utilities) and providing subsidies to boost agricultural production.

As part of Premier Wen Jiaobao's program to create "a new socialist countryside", the government has made the compulsory nine-year education free. It is even providing students with free textbooks in many areas. The spending on medical services for rural residents has increased, too. All these are all steps in the right direction.

But it remains unclear whether Beijing will be able to address the growing grievances of China's poor before some trouble erupts. Although billions of dollars have been promised to "level the playing field", the number of mass incidents (protests) in China continues to grow (thousands are now reported every year). Much of the country's rural population remains skeptical about the future, complaining constantly against corruption and cronyism in local administrations.

Millions of ordinary farmers and laborers are waiting to see whether Beijing can deliver on its promises. The central government is committed to helping people who have been left behind. But this might not be enough. It is time China's new millionaires and billionaires "chipped in" and gave back something of what they have earned from society.

For example, assistance from the private sector could go a long way toward building modern hospitals, universities and other facilities that would help create a harmonious society. Moreover, salaries of employees ought to increase proportionally with the profits of private enterprises.

In short, there is much that could and should be done by the 10 richest percent of the population that has enjoyed most of the privileges in this great nation.

Dennis V. Hickey is endowed professor of political science at Missouri State University (MSU), and Takashi Kawamoto is a student in the MSU graduate program in Global Studies.

(China Daily 01/27/2010 page9)