Learning to live

|

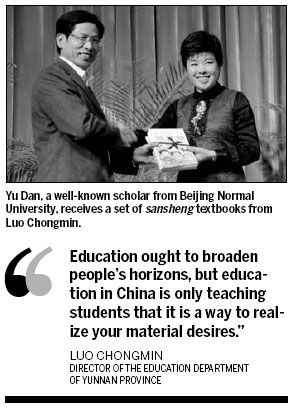

Luo Chongmin visits a primary school in a remote mountainous region in Yunnan province. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Related video: Exclusive interview with Luo Chongmin during the 2011 two sessions

Distressed by an education system that emphasizes its material benefits, a self-taught Yunnan education official shows the way out. Yu Tianyu and Yang Wanli report.

When a foreign reporter asked a kindergarten student in Guangzhou what she wanted to do when she grew up, the girl replied she wanted to become a corrupt official.

In another incident, a 9-year-old girl in Yunnan was scolded by her teacher for writing in her essay that she wanted to become a security guard.

Despite all the scolding the young girl couldn't understand why she shouldn't dream of becoming a security guard. After all, she reasoned, she felt safe and reassured every time she returned home late after school and saw the guards patrolling the residential areas.

Reports like these so shocked Luo Chongmin, an education official in Yunnan, that he decided it was time for a revolution in education.

"Education ought to broaden people's horizons, but education in China is only teaching students that it is a way to realize your material desires."

Luo was born into a farmer's family in Jiangyin county of Yunnan province in 1952. His father became a civil servant after completing middle school.

In 1965, Luo received his own admission letter to Jiangyin No 1 Middle School.

"The middle school entrance exams were very competitive at that time and only 12 of the 120 students who did the exam in my county made it," he says.

However, because of the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976), Luo had to abandon his studies after completing just one year of middle school.

He still recalls the tears that fell on his new textbooks when the school announced it was halting classes. Even so, he would often sneak into the homes of his teachers to ask questions.

But his dreams of studying were ultimately shattered when in 1969, like many other Chinese youth, Luo became a zhiqing, or educated youth, after responding to the government's call to work in the countryside.

Despite those tough times, the desire to study never left him and he taught himself traditional Chinese medicine, just because a TCM textbook was the only one he could lay his hands on.

In 1972, Luo was employed at a fertilizer plant and worked there for nine years. "I learnt a million things there - from chemistry to mechanics," Luo says.

"I was always curious about whatever I saw people do, whether it was repairing a car or fixing a machine tool," he adds.

Luo was fated to return to school when he joined Jiangyin No 1 Middle School as a cook and school worker in 1981, almost 15 years after being deprived of an education there.

But all the time that he was cooking school meals and ringing the class bell, Luo kept the dream of completing his education. In the changed climate of 1978, when the country resumed college entrance exams, he took up his abandoned textbooks and completed the entire middle school syllabus within three years.

He was 30 then, and married with two children.

He then entered a local Communist Party School and became a civil servant at the county government of Jiangyin, after graduation.

Rising through the ranks, Luo went from county-level official to county magistrate, provincial-level official, and was eventually named director of the Education Department of Yunnan in 2008.

"I firmly believe education can change people's lives," Luo says. "Although this is something many others believe in, they usually equate the change with money or power."

The nation's education system is seen as a tool for socio-economic development of the country, as well as for personal enrichment, Luo adds.

"These misplaced expectations have produced students who are competent exam-takers but lack an innovative spirit, or even common survival skills," he adds.

In 2008, Luo launched a new educational concept in Yunnan, calling it sansheng, which has since been adopted by millions of educators and parents.

Sansheng (literally, three sheng) encompasses the ideas of shengming, or life; shengcun, or survival; and shenghuo, or living. Through lectures, class discussions and extracurricular activities, sansheng seeks to complement the traditional emphases in Chinese schools so students learn to value and respect all people, adapt to different circumstances and enjoy their lives.

Sansheng textbooks convey these ideas through cartoons and stories instead of boring sermons.

The textbooks have been adopted by more than 18 Chinese provinces and cities, including Shaanxi, Henan Anhui and Qingdao in Shandong province.

Luo says Kunming now boasts sansheng centers with 40-50 models of fire stations, banks, police stations, hospitals, department stores and bakeries where children can role play to understand how these places operate.

More than 2,000 students from the city's Chuncheng Primary School attend sansheng courses once a week.

"Our teachers encourage us to get hands-on instead of just listening to their lectures and we learn by playing games and telling stories," says 12-year-old Yao Yusheng.

The courses include safety information in times of natural disasters, knowledge of environmental protection, and even natural birthing.

Chuncheng Primary School president Wang Ling says, "Students also share what they have learned with their parents and other members of the family."

Li Zhen, a 27-year-old teacher, who helps run a sansheng course, says some parents have told her that their children express their love and gratitude to them more openly after attending the course.

(China Daily 05/05/2011 page20)