Ethnic unity - the source of happiness in Xinjiang

|

Armair Yitit, who volunteers his time at the Cemetery of Revolutionary Martyrs in Yecheng county, Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, talking with local students about the history of the region. Zhu Mingjun / for China Daily |

|

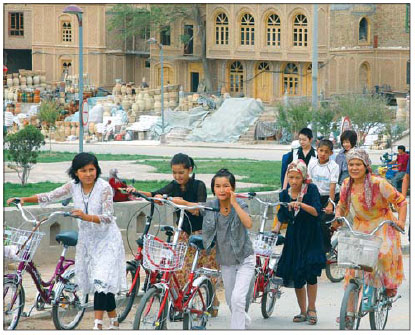

Face-lift project in the ancient Silk Road city of Kashgar. The renovation has made transportation more convenient while preserving the traditional culture of the city. Zhu Mingjun / for China Daily |

|

Night view of Urumqi, capital of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. Li Xiongxin / for China Daily |

One family with 26 members from five ethnic groups - that's the family Nur has seen grow in the village of Bazbokda, Tacheng, in China's Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

The now-43-year-old Nur was born to a Kazak father and Han mother and married a woman from the Uygur ethnic group. His brothers-in-law, the husbands of his two sisters, are from the Mongolian and Xibe ethnic groups.

"We respect ethnic differences and get along with each other very well," Nur says happily, while attributing that happiness to the one big family.

In 2007, Nur, as a village-head joined Zhu Maomin, a Han and fellow villager, in setting up a rural cooperative. The two have managed 200 mu (13.3 hectares) of farmland owned by 16 households.

"The rural cooperative is my big family. It consists of Kazaks, Uygurs, Han, and other ethnic groups," says Nur.

The families have pooled their labor to increase incomes and improve their lives, and the income per mu has grown from 70 or 80 yuan in 2007 to about 150 yuan now.

"The Han are more experienced in planting crops than our Kazaks and Uygurs, while we're good at breeding and herding. So we learn from each other," Nur explains.

"All my happiness comes from ethnic unity. In my small family, we live harmoniously. In my big family, we work together for the common good," he adds.

Nur's family is the epitome of current ethnic relations here - equality, unity, mutual assistance and harmony.

Xinjiang is a multi-ethnic province with a population of 21 million, with 47 ethnic groups.

The Uygur and Hui follow their traditional way of life and tend to focus on business and food services, while the Han often grow vegetables, and the Kazaks tend more toward pasturing.

They use their respective strengths to cooperate with one another for the common development and the same production objectives.

The social system, common political and economic organizations, and common living have helped form stable relationships among various communities and have made them closer comrades, colleagues, neighbors and friends.

Cementing ties

In the Tianshan district of Urumqi, the government is looking for at least one Uygur-speaking Han official for each of its 140 communities, within two years.

The Xinjiang government, in an April 2010 regulation, said that all new public servants need to be bilingual, so Han officials need to speak the language of another ethnic group, while officials of other ethnic groups need to know Mandarin.

The Han language, Mandarin, is the official national language and the most widely used. But, Xinjiang has many ethnic minorities who lack basic Mandarin skills. Government-organized language classes mainly focus on teaching grassroots Han officials the language of the major ethnic group, the Uygurs.

"It's very difficult to work here if you can't speak Uygur because few villagers speak good Mandarin," says Li Dehong, 38, Party chief of Baren township in Shule county, Kashgar prefecture.

Many village officials such as Li have actually taught themselves the local language in poorer rural areas in the south, where the vast majority of residents are Uygurs.

In Urumqi, the capital, Uygur language classes run by reputable, private education institutes are crowded with students. They include university students or others who hope to become public servants, business people, white-collar workers and language lovers.

Some public servants who have not attended government classes study at their own expense.

"It'll be easier for me to communicate with others if I know their language," says Liu Derong, 57, a retired accountant who studies Uygur at Xinjiang Science and Information College.

"I speak Uygur when I go to Uygur shops, and the bosses are always very happy," Liu says.

"The root of ethnic unity lies in the common people," says Hao Shiyuan, an ethnologist and anthropologist and deputy secretary-general of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Respect

"Ethnic integration is just empty talk if different ethnic groups can't be treated equally," comments Jiao Yimin, deputy Party secretary of Urumqi.

Jiao recalls his friendship with a Uygur family from Kashgar, in southwest Xinjiang, who came to Urumqi to make a living a couple of years ago.

He met the woman on the street illegally selling telephone cards and told her that her business was unlicensed and illegal, and would not help her family out of poverty.

He then introduced her to another line of work so she now has a stable job and her sons are getting a good education in Urumqi schools.

"We government officials should make people's livelihoods our top priority and give poor families guidance and a chance to get rich," Jiao says.

Urumqi's floating population mainly consists of non-Han people living around the Erdaoqiao district, an ethnic business zone, with a long history of different ethnic groups coming together to do business.

This year, the municipal government has relaxed its rules on temporary residence permits and adjusted its policies on the floating population.

It is also refurbishing some dwellings of the floating population and improving their work and living conditions.

Zeng Ying, 70, says he is happy to be moving out of his squatter's house in Heijiashan, near the Erdaoqiao market, where he has lived for three decades.

"It's small, crowded, and inconvenient," he says.

(China Daily 06/01/2011 page34)