Energy efficiency is key solution to climate change

Editor's note: Author Ulrich Spiesshofer is president and chief executive officer of ABB Ltd, a $40 billion company specializing in power and automation technologies that enable utility and industry customers to improve their performance while lowering environmental impact. The ABB Group of companies operates in around 100 countries and employs about 140,000 people.

One might think - after years of focus on global warming - that all the easy measures for reducing greenhouse gas emissions had been taken. And yet, as governments prepare for the 21st annual conference on climate change, some surprisingly low-hanging fruit remains.

I don't mean small fruit, either. I'm talking about big, high-yield fruit. Consider this: fitting energy-efficient electric motors on all pumps and fans with devices to regulate their speed would save 3,338 terawatt-hours (3.3 million gigawatt-hours), roughly equivalent to the amount of electrical energy produced in the European Union in 2013. The calculation is based on ABB's installed base of variable speed drives, which covers around 20 percent of the global market and is estimated to be saving some 445 TWh of electricity annually.

The opportunity is huge because electric motors are among the biggest consumers of energy. They power all manner of equipment and account for about 40 percent of all electricity consumed worldwide. In the European Union, they are responsible for about 12 percent of total CO2 emissions, second only to space-heating products, according to the European Commission.

In recent years the EU, along with several other countries, such as the United States and China, has imposed new rules requiring older, energy-hungry motors to be phased out. These rules, known as Minimum Energy Performance Standards, specify the minimum acceptable efficiency levels of a product, defining which products can be marketed and sold. Typically, these MEPS become more stringent over time. In the EU, for instance, rules requiring a higher efficiency class of motors came into effect in January.

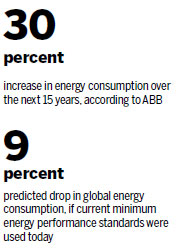

MEPS in Europe and their equivalents in other countries will ultimately lead to the upgrading of the installed base of electric motors. However, at the current pace of implementation, and taking into account loopholes and enforcement issues, they will likely fall short of the energy savings needed to achieve climate goals, especially given that global energy consumption is expected to increase by 30 percent over the next 15 years.

One reason is that MEPS specify the efficiency of individual products, in this case electric motors, rather than the efficiency of motor systems. No matter how efficient a motor is, if it cannot regulate its speed according to load, it will always be operating at full throttle. Legislation is gradually changing to take account of this - for instance, EU rules that came into force in January specify that certain (namely, less-efficient) motors must be able to adjust their speeds. But only around 10 percent of motors in service worldwide are currently equipped with (variable speed) drives that allow them to do this, even though the energy savings can be substantial - up to 50 percent in some cases. The calculation is based on ABB's installed base of variable speed drives.

Another challenge is to establish common MEPS globally. Again, progress is being made in this area, with more and more countries moving toward harmonized standards, but much remains to be done. A recent study commissioned by the European Commission called "Savings and benefits of global regulations for energy efficient products", concluded that, if the most stringent current MEPS for product energy efficiency were harmonized today, global final energy consumption would be 9 percent lower, and energy consumption due specifically to products would be 21 percent lower. This would save 8,950 TWh of electricity, equivalent to closing 165 coal-fired power plants, or taking 132 million cars of the road.

The clock is ticking on climate change. The weight of scientific opinion is that we don't have much more time to turn the tide on emissions, otherwise it will not be possible to limit global warming to two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, which is considered the maximum temperature rise we can sustain without triggering potentially catastrophic climate events.

Of all the actions that can and are being taken to limit carbon emissions and mitigate the effects of climate change, none holds out more promise than improving energy efficiency. There are numerous measures that can be undertaken immediately, without fear of harming economic growth; indeed, since most investments in energy-efficient technology are paid back within a year or two through lower energy costs, they can significantly boost competitiveness and through the replacement of old equipment generate additional economic activity. Fruit doesn't hang much lower than this.

|

ABB pioneered high-voltage direct current transmission technology 60 years ago and has been awarded about 100 HVDC projects, representing a total installed capacity of more than 120,000 megawatts and accounting for about half of the global installed base.Photos Provided To China Daily |

(China Daily 12/01/2015 page16)