New year, new voices: Three debuts for your 2017 reading list

Orlando Bird picks some superb debut novels, which flit from Sixties campus radicals to spoilt brats growing up in Rio de Janeiro

New year, new fiction - and the biggest noises are coming from the other side of the Atlantic. No surprises there, you might think, with a weary shrug. (In 2016, they were over here, taking our Booker Prize.) What is surprising, though, is the fact that these big, ambitious novels are debuts.

For a while now, America's younger writers have been sacking off the hunt for the all-knowing, all-telling Great American Novel, opting for tricksier, more intimate forms. "When history came alive, I was sleeping," says Adam Gordon, a poet traipsing round Madrid at the time of the 2004 bombings in Ben Lerner's 2011 debut, Leaving the Atocha Station. It's a long way from The Naked and the Dead.

But things are changing. We've recently had Garth Risk Hallberg's gigantic City on Fire; now one more big, sweeping American debut has come and kicked the door down: Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi.

Yaa Gyasi: Homegoing

Yaa Gyasi's Homegoing is half the length of The Nix but its historical sweep is roughly four times as wide, examining the twin legacies of colonialism and slavery. It's not downplaying the gravity of these themes to acknowledge that they have already been covered extensively. But Gyasi, who was born in Ghana and grew up in the States, has a different angle. Homegoing begins on the Gold Coast in the 18th century, and one of its central preoccupations is with how Africans became active participants in the slave trade.

Esi and Effia are half-sisters, unaware of each other's existence. Caught up in a squalid bit of local power-broking, Effia is married off to a British officer. An unenviable fate - but Esi's is much worse. She is snatched by a rival village, sold into slavery and eventually shipped to America. Each chapter follows one of the sisters' descendents, shifting between both sides of the Atlantic and ending up - via the Deep South plantations and Civil War-era Baltimore - in present-day California.

I was particularly impressed by the Ghanaian sections. Gyasi imbues indigenous life with richness and dignity, in a style that owes something - though by no means everything - to Chinua Achebe. The smell of sizzling yams hangs in the air, the landscape spreads dazzlingly wide, and people think nothing of walking 10 miles to see a neighbour.

On the other hand, this is no paean to the good times before things fell apart. Superstition thrums in the background, and regional antagonisms - once settled by a raid or two - become levers in the colonial game of divide-and-conquer ("The Asante had power from capturing slaves. The Fante had protection from trading them").

The intricate, arching structure is a risk - one you have to admire Gyasi for taking. It serves as the engine for a powerful message, giving a lineage to shattered families and an identity to people stripped of their names, as well as highlighting the more destructive aspects of inheritance: guilt and a sense of entrapment. On a page-by-page level, though, it sometimes achieves the opposite. As each chapter begins with a new generation, it can be a laborious process working out where certain characters have come from.

And the massive time frame stretches Gyasi's powers. In Beloved, a novel of unremitting intensity, Toni Morrison deals with three generations; here we have seven. There just isn't space for storylines to develop with the fullness and complexity they need, and several characters - the luckless farmer in Ghana, the rudderless junkie in Harlem - appear little more than types. Given the ambition of Gyasi's enterprise, though, and the extent to which she carries it off, these slips are easily forgiven.

Luiza Sauma: Flesh and Bone and Water

The advance for Homegoing was reportedly $1 million, and it probably says something about the nature of British book deals that our first-timers have played things much safer. But this doesn't necessarily imply a weakness: two homegrown novels, coming out this month, offer the alternative pleasures of deft, lyrical storytelling, irony and melancholy.

Flesh and Bone and Water by Luiza Sauma is a slim but arresting debut about memory and trauma. In this respect and others, it resembles Julian Barnes's 2011 Man Booker-winner, The Sense of an Ending, though without that novel's mixture of arch didacticism and remorselessly dull characters.

Our narrator is Andre Cabral, a middle-aged, Brazilian-born doctor, long settled in London but now on the brink of divorce. When a letter arrives from the old country, smelling "woody, humid, faintly tropical", it seems like a release from his dingy new bachelor pad. But the message is ominous: "I have a lot to tell you. I will make you wait, just as you made us wait."

The story goes back in time, following Andre's recollections, and we learn about his sheltered upbringing as part of Rio de Janeiro's white patrician class, as well as his relationship with the author of the letter, Luana - his family's empregada (or round-the-clock dogsbody).

Having been instructed by his father not to "f---around" with her, he goes ahead and does just that. Sauma, whose style manages to be both spare and rich, is clear-eyed about the social and racial divides in Rio, where grand old buildings brush up against favelas, and funny about Andre's brattish school friends, who can barely dress themselves.

Luana falls pregnant, which doesn't come as a surprise, but the repercussions (none of them exactly Andre's fault) are shocking - and so far-reaching that he only finds out about one of them 30 years later. This is partly because he has cut himself off from Brazil, and throughout the story there's a tension between his level tone and the behaviour he describes. "What rash decisions we make, when we're young", he says (in a rare instance of Sauma telling rather than showing). Maybe - but he's made no attempt to patch things up since.

Andre isn't a villain, though, and what he's dealing with is genuine trauma, albeit imperfectly and selfishly understood. At one point, he wonders whether his father has had a heart attack to get his attention. At another he asserts that he would never have slept with Luana if his mother hadn't died.

In its treatment of the big picture, Sauma's novel couldn't be further from the bristling, omniscient offerings of the Americans: "The dictatorship ended that year", Andre recalls. "But I don't remember how I felt about it."

Laura Kaye: English Animals

Upstairs-downstairs intrigue - with added taxidermy - is a theme in Laura Kaye's uneven but entertaining English Animals. Mirka, a young, gay Slovakian woman, takes a job at a large, respectably run-down house somewhere in the country.

Her employers are Richard, a shambling Jeremy Clarkson type with an interest in (though little talent for) hunting and stuffing animals; and his frustrated wife, Sophie, who is younger and smarter than him. They struggle to pronounce Mirka's name, but both become close to, then dependent on her. Richard discovers she has a knack for taxidermy; Sophie starts an affair with her.

This is all told from Mirka's perspective, her stark voice shading into bemusement as she watches the English doing their stuff: shooting, crosswords, binge-drinking, dressing-up. Kaye's satire usually hits the mark, coming at the expense of rural gastropubs with names like The Snooty Fox, as well as the world of hipster taxidermy (Mirka starts assembling Dazed and Confused-friendly scenes called things like "Freelance squirrels" and "Rats at an office party").

Bigger subjects are anatomised less effectively. "You should have stayed in your own country", growls Richard and Sophie's gamekeeper, apparently fresh from the set of Straw Dogs. Ironically, the m��nage a trois lacks tension precisely because Richard and Sophie's marriage is so believably rackety. They're open and easygoing about Mirka - until the novel's hysterical climax, which feels completely out of place.

Kaye is at her best when she sticks with the scalpel. It's good to see that British writers still know how to use it.

|

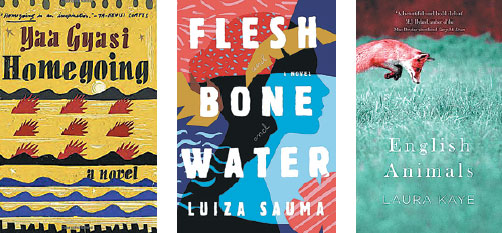

From left: The book covers for Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, Flesh and Bone and Water by Luiza Sauma, and English Animals by Laura Kaye. Provided Tochina Daily |

(China Daily 02/11/2017 page22)