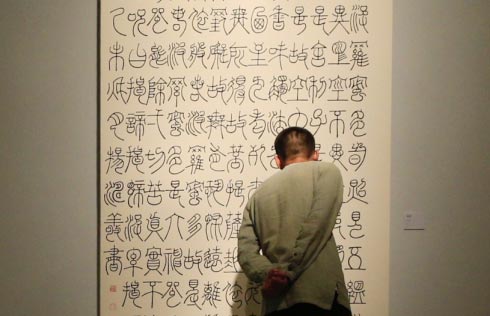

Heart in the hutong

|

|

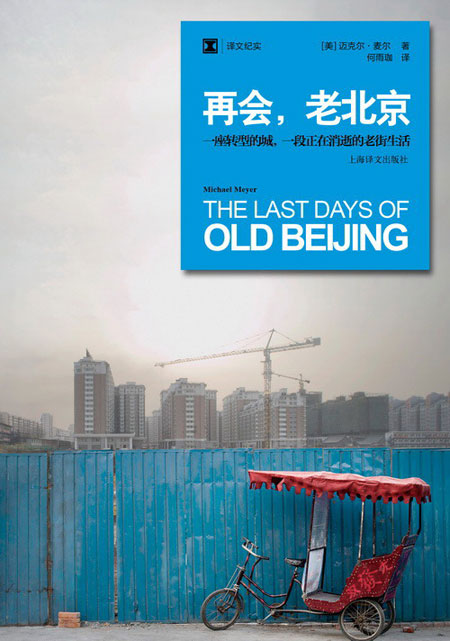

Michael Meyer's 2008 book was recently published in Chinese. Photo provided to China Daily |

Meyer says when he was "a snobbish journalist", he barely kept any contact with his interviewees after pushing them for quotes he needed for a story. But this time he tried to be friends with people, politely and patiently waiting till they offered to share.

Their stories finally started to emerge, conjuring up a world that Meyer found is not risky and disorderly as imagined by outsiders. Instead, it's a world that's "safe and full of vitality".

In this world, he had to get along with an enthusiastic old widow, his neighbor and landlady who has a personal history perhaps more revealing than the written records of the city.

He was also given a rare "opportunity" by the neighborhood's garbage man to visit a dumping ground.

He once even went to a remote village in Shaanxi province, hoping to catch up with the life of Lao Liu, a noodle-shop owner who returned home after a demolishing plan led him to bankruptcy.

Meyer's 2008 book is now being introduced in a Chinese version - hard to call a "translation" since the words are resuming their original form.

The author's pursuit of purely human-interest stories, critics say, offers a fresh approach to writing city chronicles.

In a recent public dialogue with Meyer, Liu Suli, owner of Beijing's well-known independent Wansheng Bookstore and a veteran observer of China's publishing market, said he has read many Beijing chronicles, none of which, however, is like Meyer's.

"The point of being a foreigner in this situation is not really a different perspective, but the different training he received in writing," Liu says.

"If you don't write well about people, you can hardly reveal the nature of a city."

Liu says the value of Meyer's writing is that, though he obviously has a stance, he doesn't criticize. Instead, he is like a camera, faithfully recording what he saw and heard.

Wang Chunyuan, author of the newly released Beijingers in the Eggshell, crowned Meyer's act as "a pilgrimage" of some sort because he "willingly wormed his way into the texture of the city" and freeze-framed the last moment of Beijing's traditional lifestyle before it changed.

Decades of urbanization will deprive many cities of their basic memories and lifestyles, Wang says, which is a huge "cultural sorrow".

Shabby as it is, Meyer says, the hutong is a place where some lifestyles, such as keeping pigeons, become habitual and can hardly be practiced elsewhere, where outsiders blend into locals and migrants turn into citizens, and where locals build up a solid social network and find themselves a comfortable role.

It's undeniable that the conditions are poor, and that's why many, especially young people, want to move out.

The ideal situation, Meyer says, is let those who want to stay stay and give them sanitation and safety. At any rate, he says, people should have a choice and a say.