Book is insider's account of how high-speed rail developed in China

By Xing Yi ( China Daily ) Updated: 2015-05-20 07:57:09

|

|

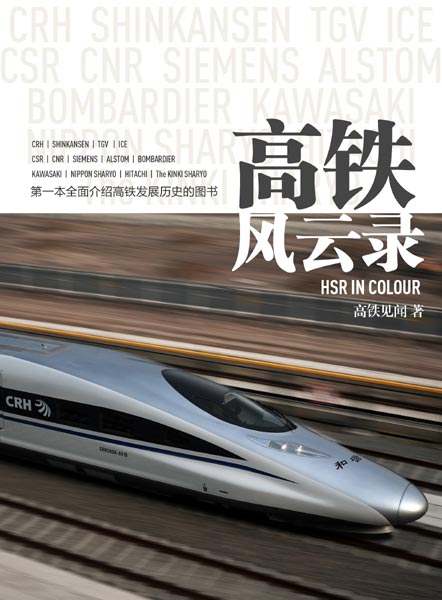

A new book will help readers get a clear picture of the country's rapid development of high-speed train network. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

By the end of 2014, the length of functioning high-speed railway lines in China exceeded more than 16,000 kilometers, more than anywhere else in the world.

High Speed Railway in Color is a crowdfunded book about how the country developed its ambitious high-speed railway project.

The book is likely to hit stores in the second half of the year and has raised 30,000 yuan ($5,000) from the public within the first five hours of the project being announced on Zhongchou.cn, a popular funding platform in China established two years ago.

Since then, it has raised three times the initial amount from more than 1,400 people.

Written by an industry insider, under the pseudonym of Gaotie Jianwen-literally translating to "high-speed train knowledge", the book recounts the history of high-speed railway in China and the rest of the world.

It talks about how China imported the first bullet trains from Japan and finally developed its own technology to make them.

The book also compares China's high-speed train development program with those in other countries, such as Japan's bullet train network Shinkansen and Germany's InterCity Express.

"There are too many rumors and misunderstandings on the Internet about Chinese high-speed train network, such as whether it is safe and why it developed so fast," says the author, who gave his surname as Xu.

"I want to help the public to get a clearer picture and to know the real story."

Having graduated from Tsinghua University in 2006, Xu first worked as a reporter at China Transportation Newspaper for four years, and then joined CSR, one of the two leading manufacturers of high-speed trains in the country.

In 2014, he started a micro blog under the pseudonym of Gaotie Jianwen on Sina Weibo, to answer online users' questions about China's high-speed railway.

The questions were interesting: Some people asked him whether riding high-speed trains frequently would expose them to radiation and others asked if raising the train's maximum speed to 350 km an hour would place passengers at risk of accidents.

Xu answered them with great patience using layman's language.

At present, he has more than 120,000 followers on his Sina Weibo account.

"New means of transportation bring changes in society, and it's understandable that people who haven't got used to it will have doubts and concerns," Xu says.

He then takes the example of Wang Shi, founder and chairman of Vanke, one of China's largest real estate enterprises.

When two high-speed trains collided in Wenzhou, killing 40 people and injuring several others in July 2011, Wang posted in his weibo micro blog: "Why are there so many accidents on our high-speed trains? Obviously, the Ministry of Railways has sacrificed safety for speed. ... It's time to hit the brakes!"

And then, in August 2014, Wang's weibo post read: "Nanjing to Shanghai, Shanghai to Hangzhou, Hangzhou to Ningbo high-speed trains. ... Fast, convenient and efficient. I like our Chinese high-speed trains!"

According to Xu, the two different emotions reflect the changing attitude of Chinese toward the nation's high-speed railways as it increasingly becomes a part of people's lives.

Much attention and praise has also been given to China's high-speed railway network by other countries, he says.

"In the past, China's high-speed rail attracted anecdotes, some of which were true but some were false," wrote Xu in the book's preface.

"In the future, I am confident that it will create more and more real legends!"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raymond Zhou:

Raymond Zhou: Pauline D Loh:

Pauline D Loh: Hot Pot

Hot Pot Eco China

Eco China China Dream

China Dream China Face

China Face