'Midwife to the dying'

By Chen Mengwei ( China Daily ) Updated: 2016-03-23 09:59:15

|

|

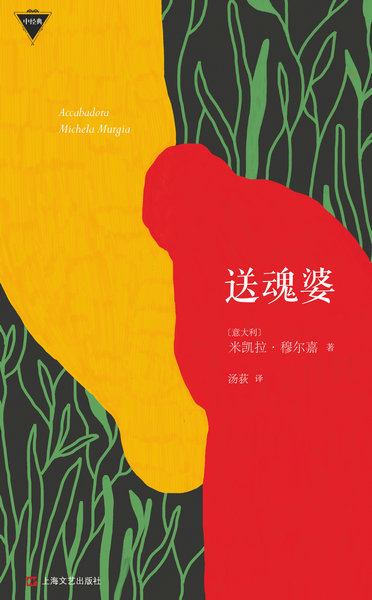

Michela Murgia's award-winning novel Accabadora is now available in Chinese.[Photo provided to China Daily] |

Michela Murgia unveils a Chinese translation of her Italian novel on 'mercy killing' of the 1950s, Chen Mengwei reports.

While big names in Italian literature, such as Italo Calvino and Umberto Eco, are known to some Chinese, the other Italian writers seem to find little mention in this country. The same is perhaps true about an average Italian's knowledge of Chinese literature, unless the author is Nobel-winner Mo Yan or someone with an international profile.

Now, bringing a little more of Italy to China is Michela Murgia, with her award-winning novel Accabadora.

The 44-year-old author, who was born in the Italian autonomous region of Sardinia, recently unveiled a Chinese translation of the book in Beijing.

Murgia's novel spotlights an illegal yet revered profession, known as accabadora, in her hometown of the 1950s. The Sardinian term loosely means "midwife to the dying" - people who gave critically ill patients a quick end with familial consent, an act somewhat similar to the modern-day concept of euthanasia.

The methods are different though. Bonaria Urrai, the story's protagonist, does it with the help of a small bottle of anesthetic and a soft pillow.

Back then, Murgia says, some did it with a hammer and others used cruder means.

"Bonaria simply uses a pillow. What matters is not how they (accabadora) end it," Murgia says in Italian. "It is how to accompany a man to the end of his life. This is an endless debate in Italy."

She speaks to China Daily with the help of an interpreter.

The practice of accabadora was never legalized in Italy, and it has been discontinued in the modern times.

In Murgia's words, the idea behind the existence of an accabadora is: No one is born into the world without another person's help, and no one should have to leave without someone helping him or her.

"Some people say, 'Oh, you're so ahead of your time in Sardinia. You've got euthanasia so long ago'. I say, 'No'. What the accabadora does is not euthanasia," Murgia says.

"Life in Sardinia used to be very fragile in the olden days. ... We needed the accabadora for that reason," she says, adding that other than the region's weak economy back then, medical care was underdeveloped.

Having said that, in her novel, Bonaria, the female "mercy-killer" never takes an old man's life if her principles aren't first met. They are simple and clear: The patient has to be dying in agony, with absolutely no hope of recovery, and the family members, including the patient if conscious, must specifically ask for it.

Once when a family of six invited Bonaria to "bring peace" to their old father, who had been lying in bed for months, they claimed the old man had lost his voice and they were making a plea on his behalf.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raymond Zhou:

Raymond Zhou: Pauline D Loh:

Pauline D Loh: Hot Pot

Hot Pot Eco China

Eco China China Dream

China Dream China Face

China Face