Silk Road archeologist protects past to promote the new

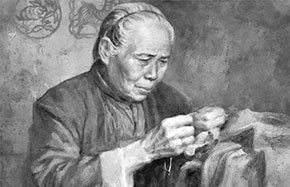

Wang Jianxin knows the ancient Silk Road like the back of his hand. He has visited hundreds of sites along the routes in the past twenty years and believes he is almost ready to lay bare the secrets of the Greater Yuezhi, an ancient nomadic kingdom.

Wang, 64, is a professor at the Northwest University of China in Xi'an, capital of the country during the peak years of the Silk Road's glories. He specializes on the corridor of territory which stretches from the city then known as Chang'an across thousands miles of Central Asia, home to many minority ethnic groups that have since vanished, often leaving very little trace.

Wang has been passionately committed to the study of ancient nomads for many years, and his resume is packed with notable archaeological research on the subject.

The disappearance of the Greater Yuezhi people has been a mystery to historians, anthropologists and linguists for many years, he said.

The ancient nomads were a branch split from the Yuezhi people who were first reported in Chinese histories living in the west of the modern Chinese province of Gansu. An answer to the mystery of their whereabouts is also about the ethnic origin and composition in Central Asian countries.

Wang found the ruins of the Greater Yuezhi's royal palace and tombs and some community sites, one of China's ten most important archaeological finds of 2007, but he was shocked when he first visited Central Asia in 2009.

"You should have come earlier! Why do you Chinese archaeologists come to join us so late?" an Uzbek archaeologists asked him. Archaeologists (and treasure hunters) from all over the world had flocked to Central Asia for archaeological or art purpose since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Wang knew Chinese archaeologists could never take their proper place on the world stage without overseas experience. So, in 2013, in the arid wilderness on the border of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, he set up his research base and began working with Uzbek colleagues. They have found a large tomb believed to belong to the royal family of the Kangju Kingdom in southern Uzbekistan.

Amriddin, director of Institution of Archaeology under the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, is optimistic about cooperation with China. Chinese archaeologists know the importance of protecting sites after excavation, and their working methodology should be promoted, he said. But despite substantial international acclaim for his work, Wang has endured plenty of difficulties in his search for final destiny of the Greater Yuezhi.

He has trekked for hours across harsh terrain to reach inaccessible sites. He broke a rib in a traffic accident but returned to work only days later.

He and his team have been widely praised for their work in the western Tianshan Range and are leading the way in archaeological cooperation along the Silk Road, said Arnayev, a Uzbek professor at Termez State University in Uzbekistan who has often worked alongside Wang.

Silk Road is a great treasure of human civilization. With looming development expected to proceed more quickly than ever, the need to protect the cultural heritage and the many unique, often fragile, environments of the countries along the Belt and Road has never been more urgent.

Wang said more overseas archaeological centers and Silk Road-related archaeological centers should be established to attract experts from various fields such as geology, biology, and environmental planning, so as to come up with more academic achievements to benefit the mutual learning among different civilizations along the Silk Road.