Testing success

|

|

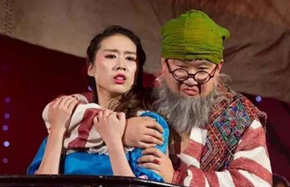

Left: Guo Yi recalls her time at Peking University, saying that the gaokao enables her to follow her dreams. Right: Jiang Xiaobin, a Tsinghua University graduate, says her success on the gaokao gives her choices. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

Life stage

A 2011 report released by a research institute affiliated with the Ministry of Education makes an interesting point about the gaokao, which resumed following the "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

It says: "Few of the top scorers on provinces' gaokao have become industry leaders. Also, except for scientists, the achievements of celebrated industry leaders, including artists, entrepreneurs and social activists, do not have direct relevance to their college educations."

Renmin University journalism professor Zhou Yong, who took the top score in Hunan province's liberal arts gaokao in 1992, opposes "deifying" champions in an interview with Sina.com.

"Top scorers can't duplicate one another's experiences," he says.

"Personal struggles mean more than status labels."

A recent, viral WeChat post by Feng Lun, one of China's most influential real estate developers, who took the exam in '78, says: "The gaokao doesn't make heroes. In China, parents' happiness depends on if their children attend a good college. You're a rebel if you choose something other than what your parents and the public expect."

He specifically addresses the conventional idea that a student entering a good high school will attend a good university, which ignores the child's happiness.

"The gaokao is an important life stage. But it's not the only way forward," he writes.

"University is a place to nurture values in addition to knowledge. Students may have different values. But this process makes them who they really want to be."