Old technology for new music

( The New York Times ) Updated: 2012-06-18 15:43:06

|

|

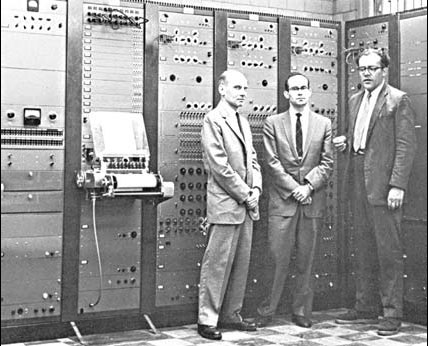

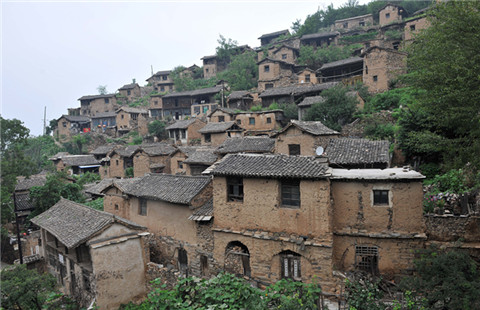

The room-size RCA Mark II Synthesizer was a state-of-the-art instrument when it was built in 1958. Columbia University Computer Music Center |

The composer Kaija Saariaho writes prolifically for conventional ensembles, but she also composes electronic music, and the works performed on a recent evening in New York not only combined live voices with recorded or electronically altered live sounds but also had video components, by Jean-Baptiste Barriere, that combined live and recorded elements.

That's a lot of technology, and several glowing Apple laptops sat on the mixing desk at the back of the hall, running it all.

Jeremy Geffen, Carnegie Hall's director of artistic planning, was interviewing Ms. Saariaho that night and he noted he had once visited the old Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in New York, where Milton Babbitt, Otto Luening and other electronic music pioneers composed on the room-size RCA Mark II Synthesizer, which was state of the art when it was built in 1958.

Anyone who had ever played electronic music could see where Mr. Geffen was going: visions of 1960s Moog modules, 1970s Buchla boxes and 1980s Atari computers passed before your eyes. He wanted to know how Ms. Saariaho deals with the technological change that renders an electronic composer's tools archaic with alarming frequency.

This, Ms. Saariaho acknowledged, was one of her worst nightmares. Several works on her program dated to the 1980s and '90s. The technology behind them had to be revisited before they could be revived.

Composers and new-music performers, meet the early-music world. Harpsichordists, viola da gamba players and devotees of wooden flutes, valveless horns and string instruments set up differently from their modern counterparts feel your pain, though only to a degree.

Specialists in music from the Middle Ages through the early Romantic era have a support industry that they can rely on: a world of instrument builders who use antique designs to reproduce the timbres and tactile qualities of early keyboards, strings, woodwinds, brasses and percussion instruments.

The parallels are not exact, of course. Everything moves immensely faster today than it did in, say, 1800, and instruments (the term now including computers and music-creation programs) that push the limits of possibility today may well be in the trash three years from now. Whether this is a function of relentless creativity and innovation or corporate profit lust - planned obsolescence run amok - the bottom line is the same: you have to scramble to keep your music playable.

Sometimes when technology changes, you cannot replace it with a digital approximation.

Ligeti's "Poeme Symphonique" for 100 metronomes (1962) should be the easiest of his scores to perform: all you have to do is wind up the 100 metronomes, start them at exactly the same time (O.K., that might not be so easy). But try finding 100 windup metronomes these days. I used to have one, but I replaced it with a battery-operated device that kept time more accurately, and now I use an iPhone app that can be set to the finest gradation of tempo I need and maintains it accurately until I turn it off.

Jenny Undercofler, the director of Face the Music, a student ensemble at the Kaufman Center in New York, had her group perform the "Poeme Symphonique" in 2008. The Kaufman Center, which is near Lincoln Center, has two music schools, so you would think that metronomes would be plentiful. But the students use newfangled ones, and Ms. Undercofler had to find a rental house that had the foresight to stockpile them.

If I were a period-instrument maker looking for expansion ideas, I would keep an eye on this. I'd buy and recondition old-fashioned metronomes, Farfisa organs, Buchla and Moog units, Atari computers and every generation of Mac I could find. I'd warehouse spare parts and archive hardware schematics and software code. I would probably not rebuild the RCA Mark II Synthesizer, but who knows where to draw the line?

Someday, specialists in 20th- and 21st-century music may decide the sampled sounds of antique technology just aren't good enough. And someone should be ready to supply the real thing.

The New York Times

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raymond Zhou:

Raymond Zhou: Pauline D Loh:

Pauline D Loh: Hot Pot

Hot Pot Eco China

Eco China China Dream

China Dream China Face

China Face