Brush captures enduring love

|

|

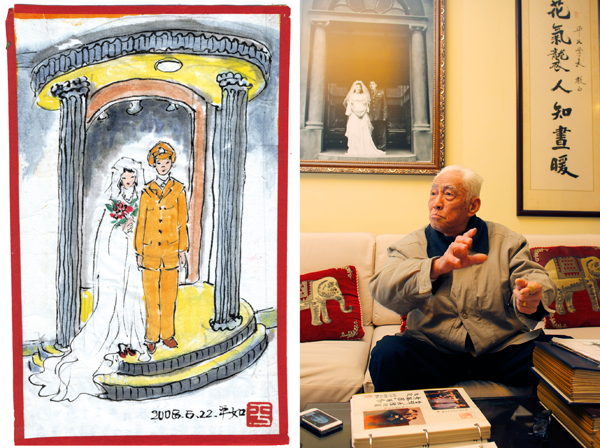

Rao Ruping, 91, displays hand-painted albums at his Shanghai home (right). Rao, a retired military man, has filled 18 albums of drawings in the past four years. Photo by Gao Erqiang / China Daily |

Man's lifelong affection for his wife moves millions on the Web.

Weeks after his wife died, Rao Pingru started to paint pictures of her.

From the first time he saw her putting on makeup in a mirror, to their wedding at which they promised "to love and cherish", to her lying in bed on her final days - all the images of their nearly 60-year marriage have been food for his art.

|

|

| An artistic autodidact |

|

|

| Underground art, literally |

"When I create her with brushstrokes, she is there, and our story doesn't perish," said Rao, 91, a retired military man and former editor.

He has filled 18 albums of drawings in the past four years, which he called Our Story.

At first, the Jiangxi native was only trying to pass time and leave something so his grandchildren could "know about their grandparents" who have been through war, poverty, sickness and, perhaps most importantly, love.

Rao met Meitang as a blind date when he came back from war in 1946.

"It's a strange thing. You just have to meet the right person to have that feeling," he said, thinking of how lovely she was.

During their early dates, Rao was too shy to say "the three words". Instead, he sang a pop song of the time, Rosemary, I Love You, to express his feelings, on a park bench in Nanchang, Jiangxi province.

The first two years of their marriage was "the sweetest time" of Rao's life, as he recalled, in spite of the turbulence following the war.

The couple adopted a happy-go-lucky policy wherever they traveled, worked and lived. They managed to escape robbery by hiding their possessions in tires while Rao was working in Guizhou province.

They teased each other about how poor they were at running an eatery, and found it fun and poetic living in a rooftop house that would shake on stormy days. "It's not hard if you don't think about it too much. We were content and happy with what we had."

In 1958, however, Rao, like thousands of other young people, was sent "to be reeducated" through labor.