Art legend made white the new black

|

|

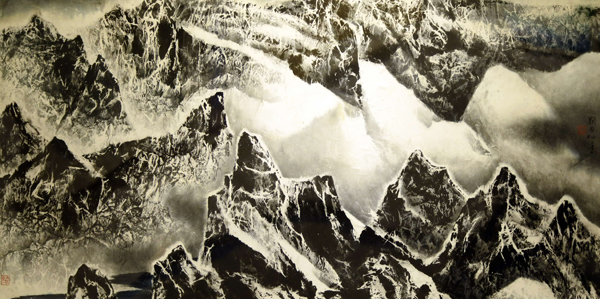

Liu Kuo-sung's work Pheriche Valley Tibet. Provided to China Daily |

Born in 1932 in Anhui, Liu started Chinese painting at the age of 14. Liu's father was a Kuomintang soldier who was killed in the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45), and the young student was accepted by a school for military kids at the age of 16.

He moved to Taiwan in 1949 with the school. Two years later Liu was accepted by the art department of Taiwan Normal University. There he learned formal Chinese painting, but he turned to Western art in his sophomore year.

In 1960, however, Liu decided there was no point in blindly following the trends of Western art. He says he wanted to enrich traditional Chinese art - which he thought had been stagnating since the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368).

"We are eager about modernizing our economy," Liu says, "but we ignore the update of our culture."

So he began to revolutionize traditional painting techniques.

He then invented the collage and marbling techniques that can create special textures to his works. But it was the invention of "Liu Kuo-sung paper" that made his painting distinctive, earning him a place in many famous art galleries around the world.

With this paper, Liu created Clouds Know No Emptiness in 1963. It was his first painting that would be collecting by museum, the Hong Kong Museum of Art.

As his artistic exploration continued, he developed such techniques as water rubbing and steeped ink.

Experts say Liu's innovative techniques invert the traditional techniques of Chinese ink paintings, which use black to outline objects, with white representing voids and empty spaces.

Liu's new approaches created a style that combines the traditional with the modern.

"Liu spent 40 years creating a new artistic language by importing Western artistic concepts into classical Chinese culture," said Michael Goedhuis, curator of London's Michael Goedhuis Gallery.

In 2011, Liu was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award of the Chinese Art and Literature Award from the Ministry of Culture in China.

Liu has donated 81 paintings to the Shandong Provincial Museum, making the museum the largest holder of his art.

"He was opposed by both the traditional school and the modern school when he turned back to Chinese painting and tried to add new elements," says Lee Mohua, Liu's wife.

"But he held out and proved he was right."

| Simple yet colorful | Framed by controversy |