Old nation's new Transfiguration

|

|

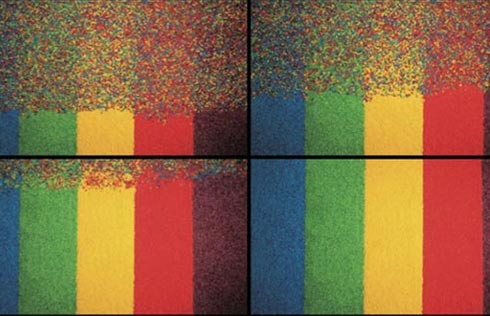

Out of Nothing - Public Foe, oil on canvas by Miao Xiaochun. |

"Transfiguration is the essence of contemporary Chinese art," says Wang Chunchen, curator of the Chinese Pavilion at this year's Venice Biennale.

"For art, transfiguration means innovation, pioneering and creativity, which in itself is in the midst of development and change," says Wang, an authority on contemporary Chinese art.

Wang chose "transfiguration" for the curatorial theme of the Chinese pavilion, where seven influential Chinese artists' works are featured, commissioned by China Arts and Entertainment Group.

The artists in the exhibit, which runs until Nov 24, are all established creators from the dynamic Beijing art scene, including He Yunchang, Hu Yaolin, Miao Xiaochun, Shu Yong, Tong Hongsheng, Wang Qingsong and Zhang Xiaotao.

"Transfiguration emphasizes things that are changing; it is the portrayal of China's social development during the last 30 years of reform and opening up," says Wang.

|

| Chinese palette |

The 48-year-old is the head of the Department of Curatorial Research of CAFA Art Museum at the China Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing and an adjunct curator of the Broad Art Museum of Michigan State University - the first and only US museum curator based in the Chinese mainland.

Chinese artists have changed because China has changed, he says.

"They are becoming more active and are taking the initiative. In this sense, transfiguration becomes a concept and, what's more, an action," he says.

"Transfiguration is a process that directs us to the future. It is a pattern that directs us to multiple possibilities. Due to transfiguration, art gained in richness with its multiple layers of significance."

China itself is a country in transfiguration, says Wang.

What is the essence of Chinese identity?

"The question of identity is complex, but we need to grasp our full and complete Chinese blood in order to preserve and not to destroy," Wang believes.

"We are blessed with a huge culture. Besides Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, we have many other essential, fundamental things. We need to slow down, to protect the environment. Perhaps I am an idealist like some of the artists."

In the pavilion, Hu Yaolin presents Thing-in-itself, which symbolically and formally evokes the dome of the Pantheon in Rome.

The message is clear, the curator says: "Hu Yaolin's art aims to preserve, restore and rebuild many old Chinese-style houses that are disappearing."

Chinese artists want to be special, Wang says. "They fancy to express their own uniqueness."

Some do this by exploring the creative possibilities that new communication technologies offer.

This is the case with Miao Xiaochun, a leading figure in today's digital art scene. His five digital works on display in Venice are inspired by the Italian masters, including Michelangelo, Titian and Caravaggio.

He remains faithful to the original compositions but not the content. His complex works are rendered through the use of vector lines and computer algorithms, expressing ecological concerns about what we eat and about the robotization of the human race.

Zhang Xiaotao, a trans-media artist, presents his virtual animations as an allegory of social vicissitudes and the future as new potential, while He Yunchang's work The Water of Venice stresses communication as a continuum of his social performance.

Shu Yong's site-specific work Guge Bricks comprises collections of phrases and words mechanically translated, displaying the multiple readings and connotations of the translations as a phenomena of globalization.

Wang says that current Chinese artistic themes travel in many directions: "They crisscross and interlink and carry this generation of Chinese peoples' understanding of the world."

Contemporary Chinese art eludes definition due to its vast diversity and even traditional art forms can take on new contemporary meaning, Wang says.

"Let's take the case of ink painting," he says. "Today you can renew the medium, artistically, psychologically and even politically."

German publisher Springer is launching a series of books on contemporary Chinese ink art, and Wang has been invited to be the curator.

In October, Wang will curate Re-China, his first exhibition at the Broad Art Museum of Michigan State University, where he will organize a five-year plan for Chinese art.