|

CIA probes renditions of terror suspects

(AP)

Updated: 2005-12-28 10:28

The CIA's independent watchdog is investigating fewer than 10 cases where

terror suspects may have been mistakenly swept away to foreign countries by the

spy agency, a figure lower than published reports but enough to raise some

concerns.

After the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, US President Bush gave the CIA

authority to conduct the now-controversial operations, called "renditions," and

permitted the agency to act without case-by-case approval from the White House

or other administration offices.

The highly classified practice involves grabbing terror suspects off the

street of one country and flying them to their home country or another where

they are wanted for a crime or questioning.

Some 100 to 150 people have been snatched up since 9/11. Government officials

say the action is reserved for those considered by the CIA to be the most

serious terror suspects.

Bush has said that these transfers to other countries �� with assurances the

terror suspects won't be tortured �� are a way to protect the United States and

its allies from attack. "That was the charge we have been given," he said in

March.

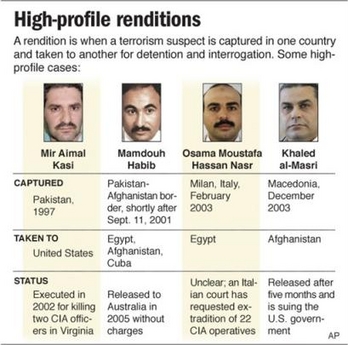

Chart shows examples of some high-profile

renditions.[AP] | But some operations are being

questioned.

The CIA's inspector general, John Helgerson, is looking into fewer than 10

cases of potentially "erroneous renditions," according to a current intelligence

official who spoke on condition of anonymity because the investigations are

classified. Others in the agency believe it to be much fewer, the official

added.

For instance, someone may be grabbed wrongly or, after further investigation,

may not be as directly linked to terrorism as initially believed.

Human rights groups consider the practice of rendition a run-around to avoid

the judicial processes that the United States has long championed. Experts with

those groups and congressional committees familiar with intelligence programs

say errors should be extremely rare because one vivid anecdote can do

significant damage.

Said Tom Malinowski, Washington office director of Human Rights Watch: "I am

glad the CIA is investigating the cases that they are aware of, but by

definition you are not going to be aware of all such cases, when you have a

process designed to avoid judicial safeguards."

He said there is no guarantee that Egypt, Uzbekistan or Syria will release

people handed over to them if they turn out to be innocent, and he distrusts

promises the U.S. receives that the individuals will not be tortured.

Bush and his aides have said the United States seeks those assurances �� and

follows up on them. "We do believe in protecting ourselves. We don't believe in

torture," he said.

In the last 18 months, his administration has come under fire for its

policies and regulations governing detentions and interrogations in the war on

terror. At facilities run by the CIA and the U.S. military, graphic images of

abuse and at least 26 deaths investigated as criminal homicides have raised

questions about how authorities handle foreign fighters and terror suspects in

U.S. custody.

Senior administration officials have tried to stress that the cases are

isolated instances among the more than 80,000 detainees held since 9/11. Yet

much remains unknown about the CIA's highly classified detention and

interrogation practices, particularly when it grabs foreigners and spirits them

away to other countries.

With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, Khaled al-Masri, a

German citizen of Lebanese descent, has sued the CIA for arbitrarily detaining

him and other alleged violations after he was captured in Macedonia in December

2003 and taken to Afghanistan by a team of covert operatives in an apparent case

of mistaken identity.

Speaking to reporters by video hookup from Germany this month, al-Masri said

he was "dragged off the plane and thrown into the trunk of a car" and beaten by

his captors in Afghanistan. Five months later, his complaint says, he was

dropped off on a hill in Albania.

Mamdouh Habib, an Egyptian-born Australian, was arrested near the

Pakistani-Afghan border shortly after 9/11 and flown to Cairo. He says for six

months he was tortured there and was later transported to Afghanistan and

Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. In 2005, he was released without charge and allowed to

return to Sydney.

Prior to 9/11, renditions were ordered to bring wanted criminals to justice.

But the purpose was broadened after the attacks to get terrorists off the

streets.

Renditions represent just a fraction of the captures handled by the CIA and

its allies. More than 3,000 foreigners have been detained in operations

involving the CIA and friendly intelligence services since 9/11, according to

the intelligence official. Sometimes the United States may merely be providing

information, training or equipment for the operations.

Countries including Jordan and Egypt are believed to cooperate with the

operations. Although Saudi Arabia is thought to be involved, its ambassador to

the United States has denied accepting any cases at the United States' request.

The spotlight on the issue has called attention to how the CIA does its work,

causing consternation among some agency officials who prefer to operate in the

shadows.

For instance, planes operated by CIA front companies are often used to move

the terror suspects from one country to another, bringing scrutiny to a secret

agency fleet that's traveled in the United States, Spain, Germany, Afghanistan,

Poland, Romania and elsewhere.

Intelligence officials said the planes are more likely to be carrying staff,

supplies or Director Porter Goss on his way to a foreign

visit.

|