-

OVER THE CHUKCHI SEA, Alaska: North of the Bering Strait, a film of new ice is filling gaps between bigger ice chunks. The sea surface was only starting to freeze up in late November, even though the winter sun slips beneath the horizon at about noon.

The freeze is overdue, experts say. "A couple of weeks ago, there was no ice at all," US Coast Guard Rear Admiral Chris Colvin, head of the agency's Alaska operations, said over the roar of the C-130 aircraft lumbering over the coastline.

That's why the Coast Guard is here, far north of its usual territory where it patrols commercial fishing grounds and the daily traffic of cruise ships, cargo ships and oil tankers.

As sea ice shrinks and open water expands and lasts longer through the year, more vessels and activity are expected in the Arctic.

The Coast Guard is trying to beat the rush.

Since 2007, when sea ice retreated to its lowest point on record, the Coast Guard has been asserting its presence.

"It's important for the Coast Guard to know what's going on up here," said Colvin, from the Coast Guard's Alaska headquarters in Juneau, about 1,770 km southeast of the Bering Strait. "It's one thing when it's completely covered by ice. But it's another when it's open water."

Arctic ice pack this year receded to its third lowest coverage since satellite records started 30 years ago, says the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado.

Scientists say Arctic ice shrinkage has profound climate effects, allowing dark ocean surfaces to retain solar heat and perpetuate a warming spiral, triggering major weather changes far to the south.

The Coast Guard sees little point in discussing why ice is sparser, said Colvin. He refers to local experts from the Inupiat Eskimo hunters.

"They couldn't care less about the politics. They'll just tell you it's changed," he said. "They'll say there's been nothing in their memories that's like what they've seen in the past 10 or 15 years."

The lure of open water has inspired some to rename the narrow passage between Russia and Alaska the "Bering Gate," said Juneau-based Coast Guard Captain Mike Inman, because it will be a vital future entry point to the Arctic.

Alaska's Arctic waters are already getting more industrial traffic, like the vessels helping oil companies search for places to drill offshore.

Cruise ships and individual watercraft increasingly carry tourists who want to experience the far north.

At least 13 adventure expeditions were mounted this summer, mostly by sailboat, Colvin said, forcing the Coast Guard to use unconventional methods to keep track.

"A lot of the information that we get is from searching websites, believe it or not. It's not like we have a whole bunch of radar tracking ships."

Adventurers have already called on the Coast Guard to rescue them. They saved two kayakers, from France and Norway, who foundered in the Bering Strait on separate treks.

Overflights are just part of the effort to boost the Coast Guard's Arctic presence. During the extended open-water season, the Coast Guard stationed two icebreakers off northern Alaska to help map the ocean floor and support other scientific work.

A community outreach program saw Coast Guardsmen teaching water-safety to local village children. They quickly discovered that the standard bright-orange life jackets did not fit a culture that values hunters' stealth on ice floes.

So the Coast Guard secured a supply of white life jackets, officials said.

Reuters

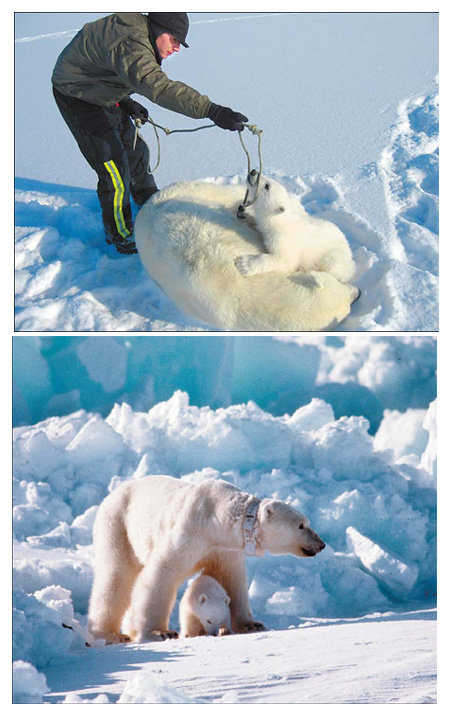

Global warming's effect on polar bears - which live on sea ice while they hunt for seals and walrus - has stirred controvesy in Alaska. Governor Sean Parnell is suing the federal government in a bid to overturn the designation of the Arctic polar bear as threatened; he believes that federal protection could negatively affect Alaska's petroleum development. Polar bears and their cubs are monitored by the US Fish and Wildlife Department. The federal agent in the top photo is capturing two cubs who were found with their dead mother. Reuters

(China Daily 12/02/2009 page10)