The man who was Mao's hero

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

2010-12-17 09:03

|

Large Medium Small |

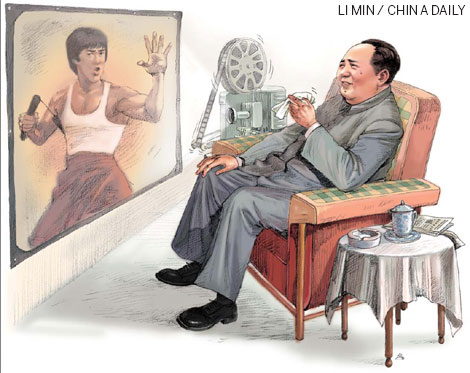

The Bruce Lee legend never fades but it might surprise some to learn that among his legion of fans was Chairman Mao, who called him a hero.

Chairman Mao Zedong (1893-1976) and Bruce Lee the martial arts legend (1940-1973) both declared - in their unique ways - that the Chinese people had "stood up".

Mao made this proclamation on the founding of the People's Republic of China, on Oct 1, 1949, Lee said it in a cinematic way that needed no translation when he kicked and smashed a wooden panel bearing the words: "Chinese and dogs not allowed", one of the iconic scenes steeped in fiery nationalism from Fist of Fury.

The words are supposedly from notices at the entrance of public parks in colonial Shanghai, and have come to symbolize the country's humiliation.

It turns out the Great Helmsman was a huge fan of the kungfu legend.

By 1974, Mao was diagnosed with a cataract and was advised by his doctors to refrain from reading. Thus he turned to movies. After a heavy dose of foreign biopics, such as those on Abraham Lincoln and Napoleon, he moved on to Hong Kong fare.

The task of collecting these films fell to Liu Qingtang, then deputy minister of the Ministry of Culture, a ballet dancer who shot to prominence by affiliating himself with Jiang Qing (Madame Mao) and starring in her "model repertory".

At that time there were no cultural exchanges between Hong Kong and the mainland. Liu flew down to Guangdong and sought the help of the local authority, but it had no recourse either. Finally, the Hong Kong bureau chief of Xinhua News Agency was summoned. He knew an attorney who was a friend of Sir Run Run Shaw, Hong Kong's movie mogul at the time.

Shaw was reluctant at first, it was said, fearing his films would be the target of mainland political campaigns. He relented, however, without knowing exactly who would be watching the movies. Among the prints on loan were three films starring Lee, then totally unknown to most mainlanders due to China's self-imposed isolation.

Reeve Wong, a noted film critic from Hong Kong, who shared the details with me, says there is one inaccuracy in the above account: Lee's main body of work was by Golden Harvest, a competitor of Shaw's studio. Wong says even so, Liu Qingtang insisted it was Shaw who loaned the movies. Here, Wong reasons that it could be a slip of the tongue, or Shaw's name stood for all the people who loaned films, because he had the biggest name.

Liu, who sat with Mao during the screenings, said he watched The Big Boss, Fist of Fury and The Way of the Dragon. Mao would burst into eulogies when he got excited.

While watching Fist of Fury for the first time, Mao dissolved in tears, Liu recalled, and said "Bruce Lee is a hero!" Mao watched the film twice more. Liu said he did not know of any other movie that Mao viewed three times.

When it came time to ship the prints back to Hong Kong, nobody dared do so lest Mao got another urge to watch them. Only after he was terminally ill were two of the movies returned.

Think of it, had Mao publicized his approbation, Lee would have instantly become an exalted figure like Lei Feng, the good Samaritan every Chinese student was encouraged to imitate.

But Lee did not need Mao's help. He became more than just a national hero, transcending geopolitical boundaries. As Mao correctly observed, Lee's movies portray the fight between good and evil and Lee invariably embodied the good. That's something everyone can relate to.

A few years ago I was asked by a film magazine to name the biggest Chinese film star of all time. After a long period of deliberation, I picked Lee. Agreed, he was not the best thespian, nor the best looking, and he had a very limited oeuvre. Yes, he was a brilliant kungfu fighter, but we trained them by the busloads in martial arts schools or opera academies, didn't we? But Lee had an appeal that went beyond the screen, or kungfu for that matter. He personified an aesthetic that shattered the stereotype of the Asian male.

It is very difficult for an Asian man to take the center stage in Hollywood productions, which shape public consciousness on a global scale. In the early years, Asian male roles were portrayed by non-Asians who resorted to painting their face yellow, slanting their eyes and adding buckteeth. Asian females had a relatively easier time of it compared with their male counterparts. Although their roles were highly restricted, they at least got to impart exotic beauty. Men were relegated to nerds, axiom-spewing sages or bad guys.

Even if you take into account the accomplishments of Jackie Chan, Jet Li and Chow Yun-fat, the situation is not much better. They are niche players with obvious limitations. And none of them project such a robust image of the Asian male as Lee did. (Japan's Toshiro Mifune, an Akira Kurosawa regular, had an opportunity to do so, but he rarely strayed from period dramas, which were too overblown to be a role model for contemporaries.)

Lee combined dexterity with a virility that busted the hoary stigmas of the Asian male. Alas his reign was too short-lived.

There is a new biopic of Lee in his youthful days, Bruce Lee, My Brother. Interestingly, the filmmakers dug out details of his life that contradicted his public persona. For example, he suffered from severe myopia. (Can you imagine Bruce Lee wearing a pair of thick glasses?) As a teenager, he was sometimes shy and would rather dance with his brother than ask the girl he had set his eyes on. Of course, tales of his street fighting are even more legendary.

Lee's screen debut was in 1950 with The Kid. I saw the movie and he was so good it is no exaggeration to say he was a child star on a par with the best in the world. In 1957, he played the idealistic younger brother in Thunderstorm, adapted from the classic play, still the stepping-stone for many a young thespian hoping for a breakthrough. It is not easy to catch snippets of Lee's early movies, but they show Lee with multi-faceted talents. Given proper guidance, he could have become Hong Kong's king of drama.

I was also surprised when I heard Lee speak English - in documentaries of course. Sure, he was born in San Francisco, but he was 3 months old when he headed to Hong Kong and only returned to the United States when he was 18. I can only say he was a quick learner.

In terms of cinematic charisma, Lee was in a league of his own. His best-known work was made in Hong Kong but gained an unprecedented following worldwide. He did something nobody had done before and nobody in Chinese cinema has surpassed since. The Chairman was spot on when he declared Lee "a hero".

| 分享按钮 |